Chapter 21. High-Quality Programming Code

In this chapter we review the basic rules and recommendations for writing quality program code. We pay attention to naming the identifiers in the program (variables, methods, parameters, classes, etc.), formatting and code organization rules, good practices for composing methods, and principles for writing quality documentation. We describe the official "Design Guidelines for Developing Class Libraries for .NET" from Microsoft. In the meantime we explain how the programming environment can automate operations such as code formatting and refactoring.

This chapter is a kind of continuation of the previous one – “Object-Oriented Programming Principles”. The reader is expected to be familiar with the basic OOP principles: abstraction, inheritance, polymorphism, encapsulation and exception handling. Those do greatly affect the quality of the code.

Content

- Video

- Presentation

- Mind Maps

- In This Chapter

- Why Is Code Quality Important?

- What Does Quality Programming Code Mean?

- Why Should We Write Quality Code?

- Identifier Naming

- Code Formatting

- High-Quality Classes

- High-Quality Methods

- Proper Use of Variables

- Proper Use of Expressions

- Use of Constants

- Proper Use of Control Flow Statements

- Defensive Programming

- Code Documentation

- Code Refactoring

- Unit Testing

- Additional Resources

- Exercises

- Solutions and Guidelines

- Demonstrations (source code)

- Discussion Forum

Video

Presentation

Mind Maps

Why Is Code Quality Important?

Let’s examine the following code:

|

{ int value=010, i=5, w; switch(value){case 10:w=5;Console.WriteLine(w);break;case 9:i=0;break; case 8:Console.WriteLine("8 ");break; default:Console.WriteLine("def ");{ Console.WriteLine("hoho "); } for (int k = 0; k < i; k++, Console.WriteLine(k - 'f'));break;} { Console.WriteLine("loop!"); } } |

Are you able to comprehend what this code does in a short glance? Does it do its job correctly, does it contain any errors?

What Does Quality Programming Code Mean?

The quality of a program encompasses two aspects: the quality perceived by the user (called external quality), and the quality in regard to the internal organization (called internal quality).

The external quality is largely determined by the operational correctness of the particular program (absence of defects). Things like usability and intuitiveness of the user interface (UI) do greatly influence the external quality as well. Performance, a term which includes operational speed, memory usage and resource utilization, also plays in the equation, whenever these things matter.

Internal quality, on the other hand, is determined by how well the program is built. It depends on whether the employed design and architecture are suitable and sufficiently simple, and whether it is easy to make a change or to add new functionality (maintainability). The comprehensibility of the implementation and the readability of the code are vital as well. In general, internal quality mostly has to do with the code of the program and its internal work.

Characteristics of Quality Code

Quality code is easy to read and understand. It is maintained easily and straightforwardly. It must withstand any kind of input without breaking or behaving strangely, and be well tested. The design and the architecture must be suitable and not over-engineered. Documentation should be at a decent level, or at least the code should be self-documenting. Formatting should be adequately chosen and applied consistently throughout the whole project.

At all levels (modules, classes, methods) there should be a strong relation and a high focus of the responsibilities (strong cohesion) – that means, a piece of code should only do one particular thing.

Functional independence (or more precisely, loose coupling) between modules, classes and methods is crucially important. Suitable and consistent naming of all program identifiers is a must. Documentation should be embedded in the code itself.

Why Should We Write Quality Code?

Let’s have a look again at our example:

|

static void Main() { int value=010, i=5, w; switch(value){case 10:w=5;Console.WriteLine(w);break;case 9:i=0;break; case 8:Console.WriteLine("8 ");break; default:Console.WriteLine("def ");{ Console.WriteLine("hoho "); } for (int k = 0; k < i; k++, Console.WriteLine(k - 'f'));break;} { Console.WriteLine("loop!"); } } |

Can you tell whether this code compiles without errors? Can you tell what it does just by glancing at it? Can you add new functionality and be sure that you will not break it up? Can you tell what the purpose of the k or the w variable is?

Visual Studio has an option for automatic code formatting. If the above code is put there and that option is invoked (via the keyboard combination [Ctrl+K, Ctrl+F]) it will be reformatted and will look completely differently. Unfortunately, the purpose of the variables will still remain unclear, but at least it should become obvious where each block ends:

|

static void Main() { int value = 010, i = 5, w; switch (value) { case 10: w = 5; Console.WriteLine(w); break; case 9: i = 0; break; case 8: Console.WriteLine("8 "); break; default: Console.WriteLine("def "); { Console.WriteLine("hoho "); } for (int k = 0; k < i; k++, Console.WriteLine(k - 'f')); break; } { Console.WriteLine("loop!"); } } |

If everyone was writing code as in the above example, it would not be possible to create big and serious software projects, because they are written by large teams of software engineers. If every team member’s code was like that, no one would ever be able to understand how the other members’ code works (and whether it works at all), and hardly anyone could even understand his / her own code.

Over the time, a serious amount of good practices have emerged and a lot of experience has been gained for writing quality code, to enable each programmer to understand and maintain his colleagues’ code. These practices endorse a variety of rules and recommendations for code formatting, identifier naming and proper program structure, all of which make writing software easier. Consistent and quality code is especially helpful when changing and maintaining a program. Quality code is flexible and stable. Because it is self-documenting and intuitive, its intentions become clear at a first sight. Quality code is easy to reuse because it does just one thing (strong cohesion), but does it well, depending on a minimal amount of other components (loose coupling), using only their public interfaces. As an end result, quality code saves time and labor, and makes the produced software more valuable.

Some programmers consider quality code as being overly simple. They tend to think that it limits their opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge. That is the reason why they write code that is hard to read, and for using features of the language which are unpopular or poorly documented. They squeeze functions on a single line. This is an entirely wrong practice.

Coding Conventions

Before continue with the recommendations on writing quality code, we should talk a bit about coding conventions. A coding convention is a set of rules for writing code, used within the boundaries of a particular organization or a project. It can include naming and formatting rules, and rules for logical composition. One such rule would recommend that class names start with a capital letter while variable names start with a lowercase letter. Another rule may state that the opening curly bracket preceding a block of statements should be on the same line, rather than on a new line.

|

Inconsistent usage of a single convention is worse and more dangerous than not having a convention at all. |

Conventions started to emerge in big and serious projects, where a large number of programmers had each been writing in their own style and everyone was adhering to their own (if any) rules. This was making the code harder to read and has forced project managers to introduce written rules. Later, the best coding conventions gained popularity and have become a de facto standard.

Microsoft provides an official coding convention called .NET Framework Guidelines and Best Practices for .NET 4.5 (http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms184412.aspx).

Since then, this coding convention has gained significant popularity and has become very widespread. The naming and formatting rules presented here are in sync with the above convention from Microsoft.

Large organizations adhere to strict conventions. Among separate teams, conventions may differ, however. Most team leaders choose to stick with the official convention of Microsoft, and they eventually extend it when necessary.

|

Code quality is not just a set of rules, which must be adhered to; it is rather a way of thinking. |

Managing Complexity

The management of complexity plays a central role when writing software. The main objective is to reduce the complexity that each member has to deal with at a certain moment. This way the brain of each of the members is burdened with less stuff to think about.

The complexity management starts from the architecture and the design. Each and every module (or rather, each autonomous code unit) should be designed with reducing complexity in mind.

Good practices should be applied at all levels – classes, methods, member variables, naming, operators, error handling, formatting, comments, etc. They transform a lot of the decisions about the code in a strictly-defined set of rules, which enables a developer to think about one thing less while reading and writing code.

The complexity management can be approached in another way: it is especially helpful for a developer to be able to abstract himself away from the big picture while writing a small piece of code. For that to be possible, the piece of code should have very clear boundaries, which are in-tact with the big picture. The old Roman rule “Divide and conquer” still applies when complexity is concerned.

The rules we are talking about later on are directed exactly towards eliminating complexity while working on a single, small piece of the system.

Identifiers are the names of classes, interfaces, structures, enumerations, properties, methods, parameters and variables. In C# and in many other languages, names are chosen by the developer. Names should not be random. They should be composed in such a way that they carry meaningful information about their purpose and their role in the code. This makes the code easier to read.

When naming an identifier, it is good to ask yourself these questions: What does this class do? What is the purpose of this variable? What is that method being used for? What information does this parameter hold?

Some good names are: FactorialCalculator, studentsCount, Math.PI, configFileName, CreateReport.

Some bad names are: k, k2, k3, junk, f33, KJJ, button1, variable, temp, tmp, temp_var, something, someValue.

It is especially bad to have a class or a method called Problem12. Some beginner programmers would give such a name to their solution of Problem 12 from the exercises. What will the name Problem12 tell you in a week or a month? If the problem is about finding a path in a labyrinth, name it PathInLabyrinth. Three months later you may encounter a similar problem and you will be able to find the labyrinth problem. How would you find it if you have named it inappropriately? Do not give a name that contains digits – this is an indication for bad naming.

|

The name of an identifier should describe its purpose. The solution of problem 12 from the exercises should NOT be called Problem12. That is a huge mistake! |

Avoid Abbreviations

Abbreviations should be avoided because they can be confusing. What does the class name GrBxPnl tell you? Isn’t GroupBoxPanel clearer? Exceptions are made for acronyms, which are more popular than their full form, for example HTML or URL. In that sense, HTMLParser is recommended over the excessive long name HyperTextMarkupLanguageParser.

Use English

One of the most basic rules is to always use English. Would you be able to understand the code of a foreigner who names variables and methods in his own language? The one and only human language, which all programmers should know, is English.

|

English is a de facto standard in writing software. Always use English for naming the identifiers in the code (variables, methods, classes, etc.). Use English for comments as well. |

Let’s see how we pick appropriate identifiers in different cases.

Consistency in Naming

Naming should be consistent. What does this mean?

In a group of methods called LoadFile(), LoadSettings(), LoadFont(), LoadImageFromFile() and LoadLibrary() it is inappropriate to have a method ReadTextFile(). The word Read is not consistent with Load.

Opposite activities should be symmetrically named (you should be able to guess the name of the opposite activity just by knowing the complementing one): LoadLibrary() goes with UnloadLibrary(), but does not go with FreeHandle(). OpenFile() goes with CloseFile(), but does not go with DeallocateResource(). It is unnatural to have AssignName next to a GetName / SetName pair.

Notice that in .NET Framework class library, big groups of classes have consistent naming: collections (the namespace and all classes use the words like Collection and List, and never their synonyms), streams are always Streams, etc.

|

Use consistent names: use the same words for the same situations, do not use synonyms. Name opposite things symmetrically. |

Names of Classes, Interfaces and Other Types

From the chapter “Principles of Object-Oriented Programming” we know that classes describe real-world objects. Class names should consist of a noun (denominative or substantive) and possibly a number of adjectives (before or after the noun). For example, a class describing an African lion should be called AfricanLion.

The recommended casing of the letters (small / capital letters) for naming types in C# is Pascal Case: the first letter of every word in the name is always uppercase and the rest of the letters are lowercase. This way it is easier to read the identifier’s name (compare the lowercase name idatagridcolumnstyleeditingnotificationservice to its Pascal Case version IDataGridColumnStyleEditingNotificationService). The latter is the public class with probably the longest name in the .NET Framework (46 characters, from System.Windows.Forms).

Let’s give a few more examples. We are to write a class, which finds the prime numbers in a given range. A good name for that class is PrimeNumbers or PrimeNumbersFinder, or maybe PrimeNumbersScanner. Bad names would be FindPrimeNumber (a verb should not be used in the name of a class) or Numbers (it is not clear what the numbers are and what we are doing with them) or Prime (a class name should not be an adjective).

How Long Should Class Names Be?

In the common case, class names should not exceed 20 characters, but sometimes this rule is not adhered to if a real-world object is described which contains numerous longer words. As we saw above, it is possible to have a class with a name that is 46 characters long. Although the name is long, it is very clear what this class does. Because of this, the recommendation for class names being less than 20 characters is only advisory, not mandatory. If you are about to choose between a class name that is short and clear and another one which is longer and as clear as the short one, prefer the short name.

A bad advice would be to abbreviate names in order to keep them short. Are the following class names clear enough: CustSuppNotifSrvc, FNFException? Obviously they are not easy readable. Names like FileNotFoundException and CustomerSupportNotificationService are much clearer, although being longer.

Naming Interfaces and Other Types

Interface names should follow the same convention as class names: they are written in Pascal Case and consist of a noun and possibly a few adjectives. In order to distinguish them from the rest of the types, the convention suggests prefixing them with an “I”.

Some good examples are: IEnumerable, IFormattable, IDataReader, IList, IHttpModule, ICommandExecutor.

Bad examples would be: List, FindUsers, IFast, IMemoryOptimize, Optimizer, FastFindInDatabase, CheckBox.

In .NET there is one more notation for naming interfaces: naming them so that they end in "able": ICloneable, IEnumerable, IFormattable. These are interfaces that most often augment the basic role of an object. Most interfaces, however, do not follow this notation, such as the IList and ICollection interfaces.

Names of Enumeration Types

A few formats are allowed for naming enumerations: [Noun] or [Verb] or [Adjective]. Names can be in singular or plural form. Every member of an enumerated type should be named in the same manner. The below examples show correctly named enumerations:

|

enum Days { Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday };

enum Color { Black, Red, Green, Blue, Yellow, Orange, Pink, Gray, White }; |

Attribute Names

Attribute names in C# should be suffixed with Attribute. For example: WebServiceAttribute. Attributes are special annotations (metadata) for a class / method or other piece of code which specify a special instruction for the compiler or the runtime. For more information see the documentation in MSDN: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/z0w1kczw(v=vs.110).aspx.

Exception Names

The convention for naming exception classes suggests that exceptions end with Exception. The name should be informative and Pascal case should be used just like when naming classes. A good example of correctly named exception class would be FileNotFoundException. A bad example for exception class is FileNotFoundError.

Delegate Names

Delegates in C# and .NET Framework should be suffixed with Delegate or EventHandler. Thus DownloadFinishedDelegate would be a good example while WakeUpNotification would not adhere to the convention. A delegate is a data type which holds a reference to method with compatible signature. For more information about delegates see the official documentation in MSDN: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms173171(v=vs.110).aspx.

Naming Namespaces

Namespaces, covered in details in the “Creating and Using Objects” chapter, should use Pascal Case like class names. The following forms are preferable:

- Company.Product.Component…

- Product.Component…

Good example for naming a namespace is: Telerik.WinControls.GridView.

Bad examples for naming namespaces are: Classes, TELERIK.CONSTANTS and Telerik_WinControlsGridView.

Assembly Names

Assembly names should match the name of the base namespace which they hold. Good examples of correctly named assemblies are:

- Telerik.WinControls.GridView.dll

- Oracle.DataAccess.dll

- Interop.CAPICOM.dll

Improper (bad) assembly names are the following:

- Telerik_WinControlsGridView.dll

- OracleDataAccess.dll

- Oracle.dll

Method names should be PascalCase, e.g. each separate word starts with an uppercase letter.

Method names should be constructed according to the following pattern: <verb> + <object>, for example PrintReport(), LoadSettings() or SetUserName(). The object can be a noun or a noun and an adjective: ShowAnswer(), ConnectToRandomTorrentServer() or FindMaxValue().

A method name should address what that method does. If you are not able to come up with a good name, you most probably have to review the method itself and whether it is decently written.

Some bad examples for method names are: DoWork() (what kind of work?), Printer() (no verb), Find2() (why not Find7() then?), ChkErr() (abbreviations are not recommended), NextPosition() (no verb).

Sometimes a single verb is a good name for a method, as long as it becomes clear what the particular method does and what objects it operates on. For example, within a Task class, the methods Start(), Stop() and Cancel() are well-named because it is clear that they start, stop or cancel a task. In other cases a single verb is inappropriate. For example, within an Utils class, methods called Evaluate(), Create() and Stop() are inadequate because the context is not entirely clear.

Methods that Return a Value

Names of methods that return a value should describe the returned value in some way, e.g. GetNumberOfProcessors(), FindMinPath(), GetPrice(), GetRowsCount(), CreateNewInstance().

Bad examples for names of methods that return a value are the following: ShowReport() (it is not clear what the method returns), Value() (should be either GetValue() or HasValue()), Student() (no verb), Empty() (should be IsEmpty()).

Whenever a value is returned, the measuring unit should be clear: MeasureFontInPixels(…), instead of MeasureFont(…).

Single Purpose of a Method

A method that does more than one thing is hard to be appropriately named: how would you call a method that does an annual income report, downloads software updates from the web and scans the system for viruses? Maybe CreateAnnualIncomesReportDownloadUpdatesAndScanForViruses?

|

Methods should have one purpose only, solving only one task, not multiple tasks at the same time! |

Methods solving multiple tasks (weak cohesion) cannot and should not be named properly. They must be refactored.

Cohesion and Naming

A name should describe everything that the method does. If a suitable name cannot be found, it most probably means that the cohesion is weak, i.e. the method does many things and should be split up into separate methods.

Here is an example: we have a method that sends an e-mail, prints a report and calculates the distance between two points in 3D Euclidean space. How would you call it? Maybe SendEmailAndPrintReportAndCalc3DDistance()? It is obvious that something is wrong with this method – we should refactor it instead of striving to find a better name. It is even worse if that method is simply called SendEmail(). This way we are misleading other programmers that this method only sends email, while in reality it does many other things. The last is very, very bad practice.

|

Naming a method misleadingly is even worse than naming it method1(). If a method calculates a cosine and we name it sqrt(), we will likely enrage other colleagues that are willing to use our code. |

How Long Should Method Names Be?

The same recommendations apply here as for classes – you should not abbreviate unless it is clear. The names should be meaningful and this is more important than its length. If the method name is too long (e.g. more than 50 characters), check whether it does a single task.

Good method names are: LoadCustomerSupportNotificationService(), Math.Sqrt(), CreateMonthlyAndAnnualIncomesReport().

Bad method names are LoadCustSuppSrvc(), CreateMonthIncReport().

Method Parameters

Parameters should be named in the following form: [Noun] or [Adjective] + [Noun]. Every word of the name should start with an uppercase letter, except for the first word. This notation is called camelCase. As with any other code element, parameter naming should be meaningful and should carry useful information.

Good examples of parameter names are the following: firstName, report, fontSizeInPixels, speedKmH, font, usersList.

Bad examples of parameter names are: p, p1, p2, populate, LastName, last_name, convertImage.

Property Names

Property names start with an uppercase letter (PascalCase, like methods), but do not contain a verb (like variables). A property name consists of an [Adjective] + [Noun] or just [Noun].

In the presence of a property called X, it is not a good practice to have a method called GetX() – it will be confusing.

If the property is of type enumeration, you could think about naming the property like the enumeration type itself. In the presence of an enumeration called CacheLevel, the property would as well be called CacheLevel.

Using the same name for the property and its type is allowed and is usual in .NET Framework class library. For example the property Cursor of the class Button in Windows Forms is of type Cursor.

Variable Names

Variable names (local variables in a method) and member-variables (fields in a class) should adhere to the camelCase notation, according to Microsoft.

Variables should have a good name, as all other identifiers in the code should. A good variable name clearly and precisely describes the object that the variable holds. Good variable names are: account, blockSize and customerDiscount. Bad names are: r18pq, __hip, rcfd, val1, val2.

A name should address the problem that the variable solves. It should answer the question “What?”, not “How?”. In this sense, good names are employeeSalary, employees. Bad names are the ones that are irrelevant to the solved problem: myArray, customerFile, customerHashTable.

|

Prefer names from the business domain in which the software operates, not from the technical names that come from the programming language: use CompanyNames rather than StringArray. |

The optimal length of a variable name is from 10 to 16 characters. The length of the name depends on the scope – variables with wider scope and a longer lifetime should have a more descriptive name:

|

protected Account[] customerAccounts; |

Variables with a narrower scope and a shorter lifetime could have shorter length:

|

for (int i=0; i < customers.Length; i++) { … } |

Variable names should be instantly understandable. Because of this it is not a good idea to remove vowels from the name in order to abbreviate it – btnDfltSvRzlts is not quite understandable.

The most important thing is: whatever naming rules are chosen for variables, they should be applied consistently throughout the code – in all the modules of the project and by the whole team. An inconsistently applied rule is worse than not having a rule at all.

Names of Boolean Identifiers

Parameters, properties and variables can be of a Boolean type. In this point we describe the specifics of these identifiers.

Their names should be a prerequisite for either truth or falsehood. For example, names like canRead, available, isOpen and valid are good. Examples of inadequate names for Boolean variables are: student, read, reader.

It would be useful if Boolean identifiers start with is, has or can (with an uppercase letter for properties), but only if this adds for clarity.

Negated names should not be used (avoid prefixing with “not”), because the following oddities may occur:

|

if (! notFound) { … } |

Good examples: configFileLoaded, hasPendingPayment, customerFound, validAddress, positiveBalance, isPrime.

Bad examples: notFound, fsafdashghg, run, programStop, player, list, findCustomerById, isUnsuccessfull.

Named Constants

Like we already know from the chapter “Defining Classes” constants in C# are something like static immutable variables and are defined as follows:

|

public struct Int32 { public const int MaxValue = 2147483647; } |

Names of constants should be written in Pascal Case or entirely in uppercase, with underscores between words (ALL_CAPS):

|

public static class Math { public const double PI = 3.14159265359; public const double GoldenRatio = 1.61803398875; } |

Named constants should clearly describe what the purpose of the particular number, string or whatever value is, rather than the value itself. A constant named number314159 is useless and confusing.

The official recommendation from Microsoft for naming the constants (const and readonly identifiers) is to use Pascal Case but some developers prefer the ALL_CAPS style which is widely used in C++ and Java.

Naming of Specific Data Types

Names of variables used as counters are recommended to contain a word that specifies that, for example usersCount, rolesCount, filesCount.

Variables that represent the state of an object should be named accordingly. A few examples: threadState, transactionState.

Temporary variables should most often have common and short names, which make obvious that they are temporary, with a very short lifetime. Good examples are index, oldValue, count. Inappropriate names are a, aa, tmpvar1, tmpvar2. Although using names like tmp and temp is acceptable it is better to choose more meaningful name like oldValue and lastIndex.

Naming by Prefixing or Suffixing

Prefix and suffix naming conventions do exist in older languages such as C. A very popular notation during many years has been the Hungarian notation. Hungarian notation is a prefix naming notation in which every variable comes with a prefix that indicates its type and purpose. For example, in Win32 API, the name lpcstrUserName would mean a variable that is a pointer to an array of characters, which ends in 0, and is interpreted as a non-Unicode string.

In C#, .NET Framework, Java and all modern programming languages, similar conventions have never gained popularity because the development environments are able to show the type of any variable. Do not use Hungarian notation in C#! Exceptions are made by some graphics libraries, to a certain extent.

Formatting, along with naming is one of the most basic prerequisites for readable code. Without proper formatting, the code is not going to be readable, whatever rules for naming and code structuring are chosen.

Formatting has two objectives: easier to read code, and, as a consequence – code that is easy to maintain. Formatting that makes the code harder to read is not good. Every aspect of formatting (indentation, empty lines, alignment, etc.) can provide benefits as well as cause harm. Formatting should follow the logical structure of the program so that the logical understanding is supported.

|

The formatting of a program should represent its logical structure. All formatting rules are introduced towards improving code readability by exposing its logical structure. |

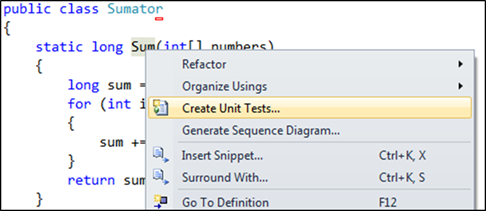

In Visual Studio, the code can be automatically formatted with the [Ctrl+K, Ctrl+F] key combination. Different standards can be applied whenever auto formatting is performed – the Microsoft conventions as well as user-defined standards are available. Try it yourself: select a piece of code and press [Ctrl+K] followed by [Ctrl+F].

Now we are going to review the formatting rules according to the coding convention of Microsoft for C#.

Why Does Code Need Formatting?

First let’s look at the below example:

|

public const string FILE_NAME ="example.bin" ; static void Main ( ){ FileStream fs= new FileStream(FILE_NAME,FileMode . CreateNew) // Create the writer for data . ;BinaryWriter w=new BinaryWriter ( fs );// Write data to Test.data. for( int i=0;i<11;i++){w.Write((int)i);}w .Close(); fs . Close ( ) // Create the reader for data. ;fs=new FileStream(FILE_NAME,FileMode. Open , FileAccess.Read) ;BinaryReader r = new BinaryReader(fs); // Read data from Test.data. for (int i = 0; i < 11; i++){ Console .WriteLine (r.ReadInt32 ()) ;}r . Close ( ); fs . Close ( ) ; } |

Is that enough as an answer?

Block Formatting

Blocks are surrounded by “{” and “}”. In C# they should be on separate lines (unlike in Java and JavaScript). The contents of the block should be indented to the right by a single tab:

|

if (some condition) { // Block contents indented by a single [Tab] // Don't use spaces for indentation } |

This rule applies for namespaces, classes, methods, conditional statements, loops, etc.

Nested blocks are indented additionally. The body of the class here is indented relative to the body of the namespace, and the body of the method is indented additionally, as well as the conditional statement:

|

namespace Chapter_21_Quality_Code { public class IndentationExample { private int Zero() { if (true) { return 0; } } } } |

Rules for Formatting a Method

According to the Microsoft’s coding convention, some formatting rules when declaring methods should be adhered to.

Formatting Multiple Method Declarations

Whenever a class has more than one method, their declarations should be separated by an empty line:

|

IndentationExample.cs |

|

public class IndentationExample {

public static void FirstMethod() { // … } // One blank line follows

public static void SecondMethod() { // … } } |

How to Put Parentheses?

The Microsoft coding convention suggests that a space should be put between a keyword (for, while, if, switch) and an opening parenthesis:

|

while (!EOF) { // … Code … } |

This is made for the keywords to stand out.

Next to a method name and before an opening parenthesis, no whitespace should be present:

|

public void CalculateCircumference(int radius) { return 2 * Math.PI * radius; } |

In this line of thought, between the name of the method and the opening parenthesis "(" there should not be any whitespace (spaces, tabs etc.):

|

public static void PrintLogo() { // … Code … } |

Formatting the Parameter List of Methods: Space after Commas

When a method has many parameters, we should put a space between the previous comma and the type of the next parameter, but not before the comma:

|

public void CalcDistance(Point startPoint, Point endPoint) |

Similarly, the same rule is applied when calling a method with more than one parameter. Before the arguments preceded by a comma, a space should be put:

|

DoSmth(1, 2, 3); |

Rules for Formatting of Types

When classes, interfaces, structures and enumerations are created, a few recommendations should be followed for formatting the code inside.

Rules for Ordering the Contents of a Class

As we know, the class name is declared on the first line, preceded by the class keyword:

|

public class Dog { |

Constants follow next. They should be ordered according to their access modifier – public constants are first, then protected and then private:

|

// Static variables public const string SPECIES = "Canis Lupus Familiaris"; |

Then follow the non-static fields. Like static fields, those labeled public are first, then protected and finally private fields follow:

|

// Instance variables private int age; |

After non-static class fields, constructor declarations follow:

|

// Constructors public Dog(string name, int age) { this.Name = name; this.age = age; } |

After the constructors, properties are declared:

|

// Properties public string Name { get; set; } |

Finally, after the properties, the methods are declared. It is recommended that methods are grouped by functionality, not by access level or scope. For example, a method with a private access modifier could easily be between two methods with a public modifier in order to make reading and understanding the code easier. We end by putting a curly bracket for the end of the class:

|

// Methods public void Breath() { // TODO: breathing process }

public void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); } } |

Formatting Rules for Loops and Conditional Statements

Formatting of loops and conditional statements follows the same rules as methods and classes. The body of a conditional statement or a loop is always put in a block beginning with “{” and ending with “}”. The opening bracket is always on a new line, immediately after the condition of the loop or the conditional statement. The body of a loop or a conditional statement is always indented to the right by a single tabulation. If the condition is long and does not fit at a single line, it is carried over on a new line and then indented to the right by two tabs. Here is an example of a correctly formatted loop and a conditional statement:

|

static void Main() { Dictionary<int, string> bulgarianNumbersHashtable = new Dictionary<int, string>(); bulgarianNumbersHashtable.Add(1, "one"); bulgarianNumbersHashtable.Add(2, "two"); bulgarianNumbersHashtable.Add(3, "three");

foreach (KeyValuePair<int, string> pair in bulgarianNumbersHashtable.ToArray()) { Console.WriteLine("Pair: [{0},{1}]", pair.Key, pair.Value); } } |

It is especially wrong to indent the body of a loop or a conditional statement as follows:

|

foreach (Student s in students) { Console.WriteLine(s.Name); Console.WriteLine(s.Age); } |

Usage of Empty Lines

It is very common for beginner programmers to insert empty lines in a chaotic manner. Really, when new lines do not harm, why shouldn’t we put them wherever we want and why should we remove them since they do not affect the meaning of the code? The reason is very simple: empty lines are used for separating parts of the program, which are not logically connected, much like new lines separate the end and the beginning of two paragraphs.

Empty lines are used to separate two methods, to separate a group of member-variables from another group of member-variables with a different logical task, for separating a group of related statements from another group of related statements.

Here is a bad example of two methods in which empty lines are used inappropriately and that hinders code readability:

|

public static void PrintList(IList<int> list) { Console.Write("{ "); foreach (int item in list) { Console.Write(item);

Console.Write(" ");

} Console.WriteLine("}"); } static void Main() { IList<int> firstList = new List<int>(); firstList.Add(1);

firstList.Add(2); firstList.Add(3); firstList.Add(4); firstList.Add(5); Console.Write("firstList = "); PrintList(firstList); List<int> secondList = new List<int>(); secondList.Add(2);

secondList.Add(4); secondList.Add(6); Console.Write("secondList = "); PrintList(secondList); List<int> unionList = new List<int>(); unionList.AddRange(firstList); Console.Write("union = ");

PrintList(unionList); } |

You see that the empty lines do not represent the logical structure of the program, and that is why they break the main rule in formatting.

If we reformat the program so that empty lines are properly used to separate logically related groups of statements, we will come up with much more readable code:

|

public static void PrintList(IList<int> list) { Console.Write("{ "); foreach (int item in list) { Console.Write(item); Console.Write(" "); } Console.WriteLine("}"); }

static void Main() { IList<int> firstList = new List<int>(); firstList.Add(1); firstList.Add(2); firstList.Add(3); firstList.Add(4); Console.Write("firstList = "); PrintList(firstList);

List<int> secondList = new List<int>(); secondList.Add(2); secondList.Add(4); secondList.Add(6); Console.Write("secondList = "); PrintList(secondList);

List<int> unionList = new List<int>(); unionList.AddRange(firstList); Console.Write("union = "); PrintList(unionList); } |

Rules for Moving to the Next Line and Alignment

When a line is longer, split it up into two or more lines and indent the lines after the first one by a single tab:

|

Dictionary<int, string> egyptianNumbersHashtable = new Dictionary<int, string>(); |

It is wrong to align similar statements according to the longest of them, since that can obstruct the maintenance of the code:

|

DateTime date = DateTime.Now.Date; int count = 0; Student student = new Strudent(); List<Student> students = new List<Student>(); |

Or

|

matrix[x, y] == 0; matrix[x + 1, y + 1] == 0; matrix[2 * x + y, 2 * y + x] == 0; matrix[x * y, x * y] == 0; |

It is wrong to align arguments to the right, based on the opening parenthesis of a method call:

|

Console.WriteLine("word '{0}' is seen {1} times in the text", wordEntry.Key, wordEntry.Value); |

The above code should be properly formatted as follows (this is not the only proper way, though):

|

Console.WriteLine( "word '{0}' is seen {1} times in the text", wordEntry.Key, wordEntry.Value); |

Let’s now discuss the classes and the best practices about using efficiently classes when writing high-quality code.

Software Design

When a system is designed, separate subtasks are often divided into separate modules or subsystems. The task that each one solves must be clearly defined. The relationships between the modules should be decided in advance, not on the go.

In the previous chapter we explained OOP and we showed how object-oriented modeling can be used to define classes of the real actors in the domain of the solved problem. We mentioned design patterns as well.

Good software design has minimal complexity and is easy to understand. It is maintained easily and changes are incorporated straightforwardly (see the "Spaghetti Code" section in the previous chapter). Every program element (method, class, module) is logically connected internally (strong cohesion), functionally-independent and minimally tied to the other modules (loose coupling). Well-designed code is easily reused.

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP)

When creating quality classes, the main rules stem from the four main OO principles: abstraction, inheritance, encapsulation and polymorphism.

Abstraction

A few basic rules:

- Public properties of a class should have the same level of abstraction.

- The interface of a class should be simple and clear.

- A class should describe only one thing.

- A class should hide its internal implementation.

Code is developed and changes and evolves over time. In spite of the evolution of classes, their interfaces should remain in-tact. A bad practice of a class having inconsistent interface is shown below:

|

class Employee { public string firstName; public string lastName; … public SqlCommand FindByPrimaryKeySqlCommand(int id); } |

The latter method is incompatible with the level of abstraction at which Employee works. The user of this class should not be aware at all that a database is used internally.

Inheritance

Do not hide methods in derived classes:

|

public class Timer { public void Start() { … } }

public class AtomTimer : Timer { public void Start() { … } } |

The method in the derived class hides the base (original) implementation. This is not recommended. If, in a rare case, this is desired and necessary, the keyword new should be used.

Move common methods, data and behavior as high as possible in the inheritance tree. This way, functionality is less likely to be duplicated and will be accessible to a wider audience.

If you have a class with a single successor only, consider this suspicious. That level of abstraction is probably unnecessary. A suspicious method would be one that re-implements a base method, but does nothing more than the corresponding base method.

Deep inheritance with more than 6 levels is hard for tracing, debugging and maintaining, and is not recommended. In a derived class, use member-variables through properties, rather than directly.

The example below demonstrates wrongly written code when inheritance should be preferred over type checking:

|

switch (shape.Type) { case Shape.Circle: shape.DrawCircle(); break; case Shape.Square: shape.DrawSquare(); break; … } |

It would make more sense if Shape was inherited by Circle and Square, which implement the virtual method Shape.Draw().

Encapsulation

A good approach is to make all members private. Only those of them that should be visible from outside could be marked protected, or eventually public.

Implementation details should be hidden. The user of a high-quality class should not be aware of its inner-workings; he should only know what it does and how it is used.

Member-variables (fields) should be hidden behind properties. Public member-variables are a manifestation of low-quality code. Constants are an exception in this regard.

The public members of a class should be consistent with the abstraction represented by this class. Do not make assumptions about the usage scenario of a class.

|

Do not rely on undocumented, internal implementation logic. |

Constructors

It is preferred that all class members are initialized in the constructor. Usage of an uninitialized class is dangerous. A half-initialized class is maybe even more dangerous. Initialize member-variables in the same order as they are declared.

Deep and Shallow Copy

When we assign values sometime we need to copy an object (make a duplicate). This can be done in two ways: deep copy or shallow copy.

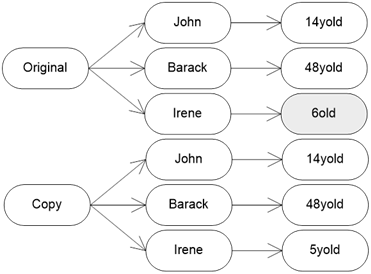

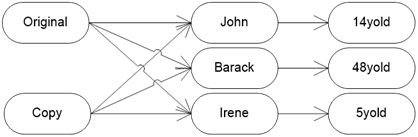

Deep copies of an object are copies in which all member-variables are copied, and their member-variables also, and so on, until no other member-variables refer to objects. In a shallow copy, only the members at the first level are copied. Example of deep copied object and its members:

Shallow copies work differently. When a shallow copy is created, the original object and its copy share some of their members:

Shallow copies are dangerous because a change in one object leads to indirect changes in others. Notice how the change of Iren’s age in the original does not affect the age of Iren in the copy when we use deep copies. With shallow copies, the change will be reflected in both places.

The quality of our methods is of significant importance to creating high-quality software and its maintenance. They contribute to more readable and more comprehensible programs. Methods do help us reduce the complexity of our software, in order to make it more flexible and easier to modify.

It is up to us, to what extent we will benefit from these advantages. The higher the quality of our methods, the more we gain from their usage. In the next paragraphs we are introducing some of the basic principles for creating quality methods.

Why Should We Use Methods?

Before talking about good method names, let’s spend some time and summarize the reasons for using methods.

A method solves a small problem. Many individual methods solve many small problems. Taken together, they solve a bigger problem – this is an illustration of the old Roman principle “Divide and conquer”, which, in this case allows us to tackle smaller problems more easily.

With methods, the overall complexity of a task is reduced: complex problems are being split up into simpler ones, additional layers of abstraction are added, implementation details are hidden, and the risk of failure is lowered. Code duplication is avoided as well. Complex sequences of actions are hidden.

Since methods are the smallest reusable unit of code, their biggest advantage is the ability they give us to reuse code. In fact, that’s exactly how methods emerged.

A method should do the work described by its name, and nothing more. If a method does not do what its name suggests, then either its name is wrong, or it does many things at the same time, or the method simply is incorrectly implemented. In any of these three cases, the method does not meet the requirements for code quality and should be refactored accordingly.

A method should either do its expected job, or should inform for an error and terminate. In .NET, informing for errors is done by throwing an exception. In case of invalid input, it is unacceptable for a method to return a wrong result. Instead, the method should inform the caller that it cannot do its job because the necessary preconditions are not met (such as invalid parameters being supplied, or an unexpected internal object state, etc.).

For example, suppose we have a method for reading the contents of a file. It should be called ReadFileContents() and should return byte[] or string, depending on whether we are treating the contents as binary or text. If the file does not exist or cannot be opened for whatever reason, the method should throw an exception rather than return an empty string or null.

Returning a neutral value (such as null) instead of an error message is generally not recommended, except in cases where that value does not collide with an error condition, such as a Find() method returning null because nothing was found. Otherwise, the caller loses its ability to handle the error, and the cause of the error is lost because of the lack of a richly informative exception.

|

A public method should either correctly accomplish exactly what its name suggests, or should inform the caller for an error by throwing an exception. Any other behavior is incorrect! |

The above rule has some exceptions when private methods are concerned. Unlike public methods, which should either work correctly or throw an exception, a compromise can be made for private methods. Since only the author of the class is supposed to call them, he should be aware of the validity of the passed arguments. Therefore, error conditions need not be handled because they can be predicted and prevented in the first place. But do not forget – this is still a compromise.

Two examples of high-quality methods:

|

long Sum(int[] elements) { long sum = 0; foreach (int element in elements) { sum = sum + element; } return sum; }

double CalcTriangleArea(double a, double b, double c) { if (a <= 0 || b <= 0 || c <= 0) { throw new ArgumentException("Sides should be positive."); } double s = (a + b + c) / 2; double area = Math.Sqrt(s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c)); return area; } |

Strong Cohesion and Loose Coupling

The rules regarding the logical relatedness of the responsibilities (strong cohesion) and the functional independence through a minimal amount of interaction with other methods and classes (loose coupling) are of a major importance when methods are concerned.

As we already explained, a method should solve only one problem, not many. A method should not solve numerous unrelated problems and should not have side effects. Otherwise, coming up with a precise and descriptive name is hard. This means that all of our methods should have strong cohesion, i.e. be concerned towards solving a single problem.

Methods should depend as little as possible on the rest of the methods in their class and on the methods / properties / fields in other classes. This concept is called loose coupling.

In the best-case scenario, a method should depend only on its parameters and not use any other data as its input or output. Such methods can be easily pulled out and reused in another project, because they are unbound to the environment in which they execute.

Sometimes methods depend on private variables declared within their class, or they alter the state of the object they belong to. This is not wrong and is entirely OK. In such a case we are talking about coupling between the method and its class. Such coupling is not problematic because the class and its internal data and logic are encapsulated: the whole class can still be moved into another project and reused without any modifications.

Most of the classes from .NET Common Type System (CTS) and .NET Framework define methods that depend only on the data within their class and the passed arguments. In standard libraries, the methods dependencies from external classes are minimal and that is why they are easy to reuse. The .NET Framework class library strongly follows the idea of loose coupling.

Whenever a method reads or modifies global data and depends on 10 additional objects, which must be initialized within the instance of its own class, it is considered a coupled to its environment and to all of these objects. This means that it functions in an overly complex way and is affected by too many external conditions, therefore the probability for an error is high. Methods that depend on too many external conditions are hard to read, understand and maintain. Strong functional coupling is bad and should be avoided as much as possible, because it often leads to spaghetti code.

Look at the same two methods like at our previous example. They are slightly modified and no longer fulfill the requirements of loose coupling and strong cohesion. Do you spot errors?

|

long Sum(int[] elements) { long sum = 0; for (int i = 0; i < elements.Length; i++) { sum = sum + elements[i]; elements[i] = 0; // Hidden side effect } return sum; }

double CalcTriangleArea(double a, double b, double c) { if (a <= 0 || b <= 0 || c <= 0) { return 0; // Incorrect result } double s = (a + b + c) / 2; double area = Math.Sqrt(s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c)); return area; } |

How Long Should a Method Be?

Throughout the years, research has been done regarding the optimal length of methods, but after all, a universal formula has not been found.

The practice shows that, in general, shorter methods (not longer than a single screen) should be preferred. Such methods are visible on the screen without scrolling and this simplifies their reading and understanding and the probability for making mistakes.

The longer a method, the more complex it becomes. Consequent modifications become considerably harder and more time-consuming than with shorter methods. These factors lead towards errors and harder maintenance.

The recommended length of a method is not more than a single screen, but this recommendation is only advisory. If a method fits on the screen, it is easier to read because scrolling is not needed. If a method is longer than one screen, we should think whether we can split it up into a few simpler methods. Since splitting is not always possible to be done in a meaningful way, the recommendation about method length is only advisory.

Although longer methods are not preferred, the latter should not be an absolute excuse for splitting up a method only to make it shorter. Methods should be as long as necessary.

|

Strong cohesion of methods is much more important than their length. |

If we are implementing a complex algorithm and consequently come up with a longer, meaningful method, which does one thing and does it well, the length is not a problem.

In any case, we should at least consider splitting up a longer method into smaller methods solving particular subtasks, whenever the method becomes too long.

Method Parameters

One of the basic rules for ordering method parameters is that the primary one(s) should precede the rest. For example:

|

public void Archive(PersonData person, bool persistent) { … } |

The opposite would be much more confusing:

|

public void Archive(bool persistent, PersonData person) { … } |

Another rule is to have meaningful parameter names. A common mistake is to tie the parameter names to their type:

|

public void Archive(PersonData personData) { … } |

Instead of the meaningless personData (which carries information only about the type), we can use a better name so that it becomes clear what kind of an object we are archiving:

|

public void Archive(PersonData loggedUser) { … } |

If there are other methods with similar parameters, their ordering should be consistent:

|

public void Archive(PersonData person, bool persistent) { … }

public void Retrieve(PersonData person, bool persistent) { … } |

It is important that no parameters are left unused. Unused parameters can only mislead the person who uses the code.

Parameters should not be used as local variables, that is, they should not be modified. Modifying method parameters makes the code harder to read and the logic becomes more convoluted. You can always declare a new variable instead of modifying a parameter. Conserving memory is not an excuse in such a scenario.

Implicit assumptions should be documented. An example would be to specify the measurement unit of a parameter to a method that computes the cosine of an angle – whether the angle is in radians or degrees, in case the name does not make it obvious.

The parameter count should not exceed 7. Seven is a special, magic number. It is proven in the psychology that the human mind cannot trace more than 7 (+/- 2) things simultaneously. As with parameter count, this recommendation is only advisory. Sometimes you need to pass more parameters. If that is the case, think about passing them as an object that represents a class with many fields. For example, instead of having an AddStudent(…) method with 15 parameters (name, address, contacts, etc.), you can reduce them by grouping logically related parameters into separate objects: AddStudent(personalData, contacts, universityDetails). This way, each of the three parameters will contain a few fields inside, and the same information will be passed to the method, but in an easier to understand form.

Sometimes it is more appropriate, from a logical standpoint, to pass only one or a few of the fields of an object, rather than the whole object. This mostly depends on whether the method should be aware of the existence of this object or not. Suppose we have a method that calculates the final grade of a given student – CalcFinalGrade(Student s). Because the final grade depends only on the previous grades and the rest of the student’s data does not matter, it would be better if only the list of grades is passed – CalcFinalGrade(IList<Grade>), instead of a Student object.

In this section we review a few good practices for using local variables.

Returning a Result

Whenever a result is returned, it should first be saved in a variable, before being returned. The following example does not hint at what exactly is returned:

|

return days * hoursPerDay * ratePerHour; |

It would be better like that:

|

int salary = days * hoursPerDay * ratePerHour; return salary; |

There are a few reasons for saving the result before returning it. For one, the additional variable contributes to self-documenting the code and makes it clear exactly what is returned. Another reason is tracing the returned value when debugging – we can stop the program from executing as soon as the value is computed and then inspect it. A third reason is that it helps us avoid long expressions, which can become quite convoluted.

Principles for Initialization

In .NET, all member-variables (fields) belonging to a class are initialized automatically at the time of being declared (unlike C/C++). This is managed by the runtime and provides for a safer environment, less prone to errors caused from incorrectly initialized memory. All reference type variables are initialized to null and all primitive types to 0 (false for bool).

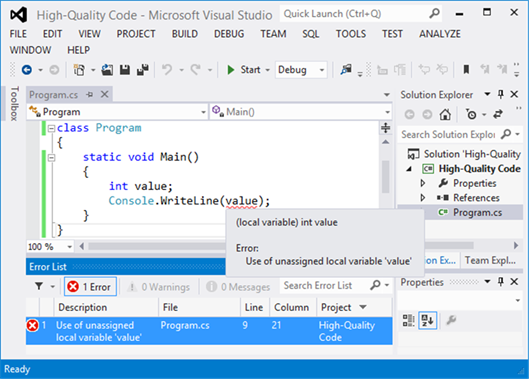

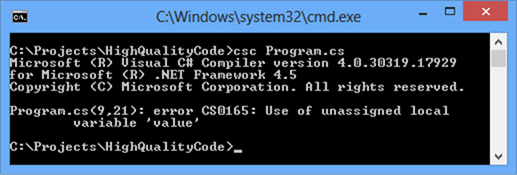

The compiler forces the explicit initialization of all local variables; otherwise a compile-time error is given. Here is an example that would cause such an error, because an attempt is made to use an uninitialized variable:

|

static void Main() { int value; Console.WriteLine(value); } |

Here is how the compilation attempt looks like in Visual Studio:

Here is how the compilation attempt looks like in the console C# compiler:

Let’s look at the following more complex example:

|

int value; if (condition1) { if (condition2) { value = 1; } } else { value = 2; } Console.WriteLine(value); |

Fortunately, the compiler is smart enough to analyze the control flow and to catch such problems – the same error is thrown, because not all scenarios assign correctly the variable.

Note that adding an else to the nested if in the above code will make it compile without errors. If the variable is not initialized at its declaration, but is assigned to a value in all the possible paths of the control flow, the compiler will still be happy.

A good practice, however, is to initialize all variables explicitly at the time of their declaration:

|

int value = 0; Student intern = null; |

Partially Initialized Objects

Some objects, in order to be properly initialized, should have at least a few of their fields set. For example, an object of type Person should have valid values set for at least the name and the family name fields. This is something the compiler cannot prevent us from forgetting.

One way to solve this problem is to remove the default constructor (the one not taking any parameters) and to add one or more constructors, which take the sufficient data as their parameters, to enable the proper initialization of the object. This is the sole purpose of parameterized constructors.

Declaring a Variable within a Block or a Method

According to the coding convention for .NET, a local variable should be declared at the beginning of its enclosing block or method:

|

static int Archive() { int result = 0; // beginning of method body // … Code … } |

Another example:

|

if (condition) { int result = 0; // beginning of an "if" block // … Code … } |

An exception is made for variables declared within the initialization part of a for-loop:

|

for (int i = 0; i < data.Length; i++) { … } |

The above recommendation is pretty disputable. Most good programmers prefer to declare a local variable as close to its intended place of use as possible. This helps reduce a variable’s lifetime (refer to the next paragraph), and, at the same time, the probability for mistakes.

Scope, Lifetime and Span of Variables

The term variable scope actually denotes how “famous” a variable is. In .NET, three layers of variable scope exist: static variables, member-variables of a class (fields), and local variables inside a method.

Minimizing the Variable Scope

The wider the scope of a variable, the higher the probability that more code will be tied to it, thereby increasing the level of coupling. Since strong coupling is not desirable, variable scope should be as narrow as possible.

A good approach in using variables is to initially declare them with the minimal scope, and extend it only when necessary. This is a natural way of assigning a variable the scope it needs. If you don’t know what scope to use, start with private and if needed, switch to protected or public.

Static variables should best be private and accessing them should be controlled via appropriate methods.

Here is an example of bad semantic coupling based on a static variable, a horribly bad practice:

|

public class Globals { public static int state = 0; }

public class Genious { public static void PrintSomething() { if (Globals.state == 0) Console.WriteLine("Hello."); else Console.WriteLine("Good bye."); } } |

If the state variable was marked private, such coupling would be impossible, at least not possible directly.

Minimizing the Variable Span

The span of a variable corresponds to the average amount of lines between its occurrences in the code. Considering minimal variable span, variables should be declared and initialized as close as possible to their first occurrence in the code, and not necessarily in the beginning of a method or a code block.

Keep the variable span as small as possible! This improves the code quality, readability, understandability and maintainability because less code needs to be inspected in order to read and understand the code.

Minimizing the Variable Lifetime

The lifetime of a local variable inside a method lasts between the place of its declaration (the beginning of a block, most usually), until the end of the enclosing block. Class fields (member-variables) exist as long as their class is instantiated. Static variables last throughout the entire execution of the program.

As you may guess, the lifetime should be kept minimal. This reduces the lines of code that you should consider at the same time when reading the code. This will maximized the portion of the code you can safely ignore when you read the code. This will reduce the total complexity in your brain, because it works better with smaller and simpler pieces of code, right?

Minimizing the Variable Span and Lifetime – Example

Below we have an example of bad use of local variables (unnecessarily large span):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

int count; int[] numbers = new int[100];

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length; i++) { numbers[i] = i; } count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length / 2; i++) { numbers[i] = numbers[i] * numbers[i]; }

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length; i++) { if (numbers[i] % 3 == 0) { count++; } }

Console.WriteLine(count); |

lifetime = span = |

In this example, the count variable’s purpose is to count the numbers, which are evenly divisible by 3. It is used only in the last for loop, but is declared and initialized long before it.

What's wrong with the above code? If you try to read it and find how the count is calculated, you will need to inspect all its 23 lines, right? The code might be written differently and the variable count might be declared and zeroed just before the last for-loop. Thus if we need to read the code and find how count is calculated, we will need to inspect only 10 lines, not 23.

See below how the above code fragment can be refactored in order to reduce the lifetime and span of the count variable:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 |

int[] numbers = new int[100]; for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length; i++) { numbers[i] = i; }

for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length / 2; i++) { numbers[i] = numbers[i] * numbers[i]; }

int count = 0; for (int i = 0; i < numbers.Length; i++) { if (numbers[i] % 3 == 0) { count++; } }

Console.WriteLine(count); |

lifetime =

span = 3.33 |

It is important that the programmer tracks the usage of a particular variable, along with its scope, span and lifetime. The main objective is to reduce the scope, the lifetime and the span as much as possible. This leads to an important rule about correctly using variables:

|

Declare local variables as late as possible, immediately before using them for the first time. Initialize them at the time of declaration. |

Variables with a wider scope and a longer lifetime should have more descriptive names, such as totalStudentsCount instead of count. That is because they occur at more locations within a larger piece of code, and hence the context around them is not going to be entirely clear.

Variables that span across just 4-5 lines can have short and simple names, for example count. They do not need long names because their purpose becomes clear from their limited context (a few lines), and ambiguities can rarely arise there.

Use of Variables – More Rules

A very important rule is to use a variable for one purpose only. The excuse that memory is conserved the other way is not generally convincing. If a variable is used for multiple different purposes, what name can we give it? Consider a variable that is used to count the number of students, and occasionally the count of their grades. How would you call it: count, studentsCount, gradesCount or studentsOrGradesCount?

|

Use one variable for a single purpose only. Otherwise, an appropriate name cannot be found. |

Unused local variables should not be present in the code. Their declarations alone are useless. Fortunately, most of the decent development environments do warn you about such anomalies.

The use of local variables with hidden meaning should be avoided. For example, John has left the variable X for Tom to see, so that he could get to the conclusion to implement another method that would use that same variable. Didn’t get it? Good, let’s hope you don’t do it either.

When using expressions, the simple rule is: avoid complex expressions! A complex expression is one that performs more than one thing:

|

for (int i = 0; i < xCoord.Length; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < yCoord.Length; j++) { matrix[i][j] = matrix[xCoord[FindMax(i) + 1]][yCoord[FindMin(i) + 1]] * matrix[yCoord[FindMax(i) + 1]][xCoord[FindMin(i) + 1]]; } } |

In the above sample we have a complex calculation, which fills a given matrix based on a computation over some coordinates. It is in fact very hard to understand what exactly is going on, because the used expressions are overly complex.

There are many reasons to avoid the use of complex expressions as in the above example. Let’s mention a few:

- Code becomes hard to read. Therefore, tracing what is going on and whether the code is correct becomes hard, too.

- Code is hard to maintain – think about the effort involved in fixing an error, in case the code does not work as expected.

- Code is hard to fix in case of defects. If the above code throws IndexOutOfRangeException, how would we know exactly which array has been involved? It could be xCoord or yCoord or matrix, occurrences of which are all scattered within the expressions.

- Code is hard to debug. In case of an error, it would be much harder to debug a complex expression because it stays on a single line, and debuggers step through the code in terms of lines.

All of these reasons suggest that writing complex expressions is harmful and should be avoided. Instead of a single complex expression, we can write a few less complex ones and save them in variables with descriptive names. In this way the code becomes simpler, easier to read and understand and easier to maintain, debug and fix.

Let’s rewrite the above code without using complex expressions:

|

for (int i = 0; i < xCoord.Length; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < yCoord.Length; j++) { int maxStartIndex = FindMax(i) + 1; int minStartIndex = FindMax(i) - 1; int minXcoord = xCoord[minStartIndex]; int maxXcoord = xCoord[maxStartIndex]; int minYcoord = yCoord[minStartIndex]; int maxYcoord = yCoord[maxStartIndex]; matrix[i][j] = matrix[maxXcoord][minYcoord] * matrix[maxYcoord][minXcoord]; } } |

Notice how simple and readable the code has become. Without knowing the exact calculation that this code is supposed to do, it is still hard to understand it, but at least we can debug it in case of an exception and find which line is causing it, and eventually fix it.

|

Do not write complex expressions. Only one operation should be performed at one line, otherwise the code becomes hard to read, maintain, debug and modify. |

Well written code should not contain “magic numbers” and “magic strings”. Such constants are all the literals in a program having a value other than 0, 1, -1, "" and null (with little exceptions).

In order to explain the concept why we need named constants, let’s examine the code below. In this code we use the number 3.14159206 (?) three times (directly and in a formula), which introduces duplicated code. If, for example, we decide to increase the precision of this constant or change it, we will need to modify the program at three different locations:

|

public class GeometryUtils { public static double CalcCircleArea(double radius) { double area = 3.14159206 * radius * radius; return area; }

public static double CalcCirclePerimeter(double radius) { double perimeter = 6.28318412 * radius; return perimeter; }

public static double CalcElipseArea( double axis1, double axis2) { double area = 3.14159206 * axis1 * axis2; return area; } } |

It comes to mind that it is better to define the repeating values only once on the code. In .NET such values are declared as named constants as follows:

|

public const double PI = 3.14159206; |

After this declaration, the PI constant is accessible to the whole program and can be used an unlimited number of times. In case we need to change the value, we change it at one location only, and the changes are reflected everywhere. Here is how our GeometryUtils class looks after declaring the number 3.14159206 as a named constant:

|

public class GeometryUtils { public const double PI = 3.14159206;

public static double CalcCircleArea(double radius) { double area = PI * radius * radius; return area; }

public static double CalcCirclePerimeter(double radius) { double perimeter = 2 * PI * radius; return perimeter; }

public static double CalcElipseArea( double axis1, double axis2) { double area = PI * axis1 * axis2; return area; } } |

When to Use Constants?

The use of constants allows us to avoid the use of “magic numbers” and strings in our programs, and enables us to give names to the numbers and strings we use. In the above example not only we avoided code duplication, but we documented the fact that the number 3.14159206 is the well-known mathematical constant ?.

Constants should be used whenever we need to use numbers or strings whose origin and meaning are not obvious. Constants should generally be defined for every number or string that is used more than once in a program (with some exceptions).

Here are a few typical cases in which named constants should be used:

- For filenames the program operates on. They need to be frequently changed and it is convenient to have them as named constants at the beginning of the program.

- For constants taking part in mathematical expressions. A good constant name improves the chance of understanding the formula.

- For buffer sizes and sizes of memory blocks. These sizes often need to be changed and that is why it is convenient to have them declared as named constants. Apart from that, using a constant named READ_BUFFER_SIZE rather than the number 8192 makes the code a lot more readable and comprehensible.

When Not to Use Constants?

Although many books recommend that all numbers and strings except 0, -1, 1, "" and null are best declared as named constants, there are a few exceptions in which declaring constants can be harmful. Remember, declaring constants is made in order to improve the readability and the maintainability of the code. When a constant does not contribute to the readability of the code, you should avoid it.

Here are a few situations in which using a named constant can be harmful:

- Error messages and other messages intended for the user (“Enter your name”, for example). Making such strings named constants will actually hinder the readability.

- SQL queries in named constants are not recommended (in case you are using a database, queries are usually written in SQL, and that is usually a string in the terms of the programming language).

- Button labels, dialog box titles, menu entries and captions of other UI components should not be declared as named constants.

The .NET Framework provides libraries that facilitate internationalization and allow exporting all the messages, captions and labels from the UI in special resource files. These are not constants, however. This approach is encouraged if the program you are writing will have to be internationalized.

|

Use named constants to avoid the usage and duplication of magic numbers and strings, and mostly to improve code readability. If the introduction of a named constant hinders the readability, better leave the hardcoded value in the code! |

Proper Use of Control Flow Statements

Control flow statements are represented by loops and conditional statements. We are going to review the good practices for using them properly.

With or Without Curly Brackets?

Loops and conditional statements allow their body to not be surrounded by brackets, in case the body consists only of a single statement. This can be dangerous. Consider the following example:

|

static void Main() { int two = 2; if (two == 1) Console.WriteLine("This is the ..."); Console.WriteLine("... number one."); Console.WriteLine( "Example of an if-clause without curly brackets."); } |

We are expecting to see only the last sentence, aren’t we? The result is a bit unexpected:

|

... number one. Example of an if-clause without curly brackets. |

That is because an if-statement without curly brackets only takes the first statement as its body, regardless of the indentation, which makes matters confusing.

|

Always enclose the body of loops and conditional statements in curly brackets – { and }. |

Proper Usage of Conditional Statements

Conditional statements in C# are represented by the if-else and the switch-case statements.

|

if (condition) {

} else {

} |

Deep Nesting of Conditional Statements

Deep nesting of if statements is a bad practice because it obstructs the comprehensibility of the code:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

private int Max(int a, int b, int c, int d) { if (a < b) { if (b < c) { if (c < d) { return d; } else { return c; } } else if (b > d) { return b; } else { return d; } } else if (a < c) { if (c < d) { return d; } else { return c; } } else if (a > d) { return a; } else { return d; } } |

This code is hardly readable because of the deep nesting. In order to improve it, we could introduce a few more methods where parts of the logic are exported and isolated. Here is how we could do that:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

private int Max(int a, int b) { if (a < b) { return b; } else { return a; } }

private int Max(int a, int b, int c) { if (a < b) { return Max(b, c); } else { return Max(a, c); } }

private int Max(int a, int b, int c, int d) { if (a < b) { return Max(b, c, d); } else { return Max(a, c, d); } } |

Extracting parts of the code into separate methods is the easiest and most efficient way to reduce the level of nesting of a group of conditional statements, while preserving their logic.

The refactored method is split into a few smaller ones. The overall length of the code has been decreased by 9 lines. Each of the new methods is simpler and easier to read. As a side benefit, we get two methods that can be easily reused for other purposes.

Proper Use of Loops

Proper use of the different looping constructs is very important to the creation of quality software. In the next paragraphs we outline some of the principles, which help us decide when, and how to use a particular loop construct.

Choosing an Appropriate Looping Construct

If we are not able to decide whether to use for, while or do-while loop, we can easily pick up one, adhering to the following principles.