Chapter 14. Defining Classes

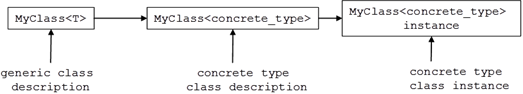

In this chapter we will understand how to define custom classes and their elements. We will learn to declare fields, constructors and properties for the classes. We will revise what a method is and we will broaden our knowledge about access modifiers and methods. We will observe the characteristics of the constructors and we will set out how the program objects coexist in the dynamic memory and how their fields are initialized. Finally, we will explain what the static elements of a class are – fields (including constants), properties and methods and how to use them properly. In this chapter we will also introduce generic types (generics), enumerated types (enumerations) and nested classes.

Content

- Video

- Presentation

- Mind Maps

- In This Chapter

- Custom Classes

- Usage of Class and Objects

- Organizing Classes in Files and Namespaces

- Modifiers and Access Levels (Visibility)

- Declaring Classes

- The Reserved Word "this"

- Fields

- Methods

- Accessing Non-Static Data of the Class

- Hiding Fields with Local Variables

- Visibility of Fields and Methods

- Constructors

- Properties

- Static Classes and Static Members

- Structures

- Enumerations

- Inner Classes (Nested Classes)

- Generics

- Exercises

- Solutions and Guidelines

- Demonstrations (source code)

- Discussion Forum

Video

Presentation

Mind Maps

The aim of every program written by the programmer is to solve a given problem based on the implementation of a certain idea. In order to create a solution, first, we sketch a simplified actual model, which does not represent everything, but focuses on these facts, which are significant for the end result. Afterwards, based on the sketched model, we are looking for an answer (i.e. to create an algorithm) for our problem and the solution we describe via given programming language.

Nowadays, the most used programming languages are the object-oriented. And because the object-oriented programming (OOP) is close to the way humans think, using one easily allows us to describe models of the surrounding life. Certain reason for this behavior is, because OOP offers tools to draw the set of concepts, which outline classes of objects in every model. The term – class and the definition of custom classes, different from the .NET system framework’s, is built-in feature of the C# programming language. The purpose of this chapter is to get us know with it.

Let’s Recall: What Does It Mean Class and Object?

Class in the OOP is called a definition (specification) of a given type of objects from the real-world. The class represents a pattern, which describes the different states and behavior of the certain objects (the copies), which are created from this class (pattern).

Object is a copy created from the definition (specification) of a given class, also called an instance. When one object is created by the description of one class we say the object is from type "name of the class".

For example, if we have a class type Dog, which describes some of the characteristics of a real dog, then, the objects based on the description of the class (e.g. the doggies "Fido" and "Rex") are from type class Dog. It means the same when the string "some string" is from class type String. The difference is that objects from type Dog is are copies of the class, which is not part of the system library classes of the .NET Framework, but defined by ourselves (the users of the programming language).

What Does a Class Contain?

Every class contains a definition of what kind of data types and objects has in order to be described. The object (the certain copy of this class) holds the actual data. The data defines the object’s state.

In addition to the state, in the class is described the behavior of the objects. The behavior is represented by actions, which can be performed by the objects themselves. The resource in OOP, through which we can describe this behavior of the objects from a given class, is the declaration of methods in the class body.

Elements of the Class

Now, we will go through the main elements of every class, and we will explain them in details latter. The main elements of a C# classes are the following:

- Class declaration – this is the line where we declare the name of the class, e.g.:

|

public class Dog |

- Class body – similar to the method idioms in the language, the classes also have single class body. It is defined right after the class declaration, enclosed in curly brackets "{" and "}". The content inside the brackets is known as body of the class. The elements of the class, which are numbered below, are part of the body.

|

public class Dog { // … The body of the class comes here … } |

- Constructor – it is used for creating new objects. Here is a typical constructor:

|

public Dog() { // … Some code … } |

- Fields – they are variables, declared inside the class (somewhere in the literature are known as member-variables). The data of the object, which these variables represent, and are retained into them, is the specific state of an object, and one is required for the proper work of object’s methods. The values, which are in the fields, reflect the specific state of the given object, but despite of this there are other types of fields, called static, which are shared among all the objects.

|

// Field definition private string name; |

- Properties – this is the way to describe the characteristics of a given class. Usually, the value of the characteristics is kept in the fields of the object. Similar to the fields, the properties may be held by certain object or to be shared among the rest of the objects.

|

// Property definition private string Name { get; set; } |

- Methods – from the chapter "Methods" we know that methods are named blocks of programming code. They perform particular actions and through them the objects achieve their behavior based on the class type. Methods execute the implemented programming logic (algorithms) and the handling of data.

Here is how a class looks like. The class Dog defined here owns all the elements, which we described so far:

|

// Class declaration public class Dog { // Opening bracket of the class body

// Field declaration private string name;

// Constructor declaration (peremeterless empty constructor) public Dog() { }

// Another constructor declaration public Dog(string name) { this.name = name; }

// Property declaration public string Name { get { return name; } set { name = value; } }

// Method declaration (non-static) public void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("{0} said: Wow-wow!", name ?? "[unnamed dog]"); } } // Closing bracket of the class body |

At the moment we will not explain in greater details this code, because the related information will be presented later in this chapter.

In the chapter "Creating and Using Objects" we saw in details how new objects of a given class are created and how they can be used. Now, shortly we will revise this programming technique.

How to Use a Class Defined by Us (Custom Class)?

In order to be able to use a given class, first we need to create an object of it. This is done by the reserved word new in combination with some of the constructors of the class. This will create an object from a given class (type).

If we want to manipulate the newly created object, we will have to assign it to a variable from its class type. By doing it, in this variable we will keep the connection (reference) to the object.

Using the variable, and the “dot” notation, we can call the methods and the properties of the object, and as well as gain access to the fields (member-variables).

Example – A Dog Meeting

Let’s have the example from the previous section where we defined the class Dog, describing a dog, and let’s add a method Main() to the class. In this method we will demonstrate how to use the mentioned elements until here: create few Dog objects, assign properties to these objects and call methods on these objects:

|

static void Main() { string firstDogName = null; Console.Write("Enter first dog name: "); firstDogName = Console.ReadLine();

// Using a constructor to create a dog with specified name Dog firstDog = new Dog(firstDogName);

// Using a constructor to create a dog wit a default name Dog secondDog = new Dog();

Console.Write("Enter second dog name: "); string secondDogName = Console.ReadLine();

// Using property to set the name of the dog secondDog.Name = secondDogName;

// Creating a dog with a default name Dog thirdDog = new Dog();

Dog[] dogs = new Dog[] { firstDog, secondDog, thirdDog };

foreach (Dog dog in dogs) { dog.Bark(); } } |

The output from the execution will be the following:

|

Enter first dog name: Axl Enter second dog name: Bobby Axl said: Wow-wow! Bobby said: Wow-wow! [unnamed dog] said: Wow-wow! |

In the example program, with the help of Console.ReadLine(), we got the name of the objects of type dog, which the user should input.

We assigned the first entered string to the variable firstDogName. Afterwards we used this variable when we created the first object from class type Dog – firstDog, by assigning it to the parameter of the constructor.

We created the second object Dog, without using a string for the name of the dog in the constructor. With the help of Console.ReadLine() we got the name of the dog and then the value was assigned to the property Name. This is done by using a “dot” convention, applied to the variable, which keeps the reference to the second object from type Dog – secondDog.Name.

When we created the third object from class type Dog, we used for the name of the dog its default value which is null. Note that in the Bark() method dogs whthout name (name == null) are printed as “[unnamed dog]”.

Afterward we created an array from type Dog, by initializing it with the three newly created objects.

At the end, we used a loop, to go through the array of objects from type Dog. For every element from the array we again used the “dot” notation, be calling the method Bark() for the particular object: dog.Bark().

Nature of Objects

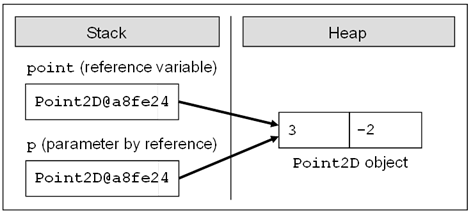

Let’s revise, when we create an object in .NET, one consists from two parts – the significant part (data), which contains its data and it is located in the memory of the operating system called a dynamic memory (heap) and a reference part to this object, which resides in the other part of the operating system’s memory, where are stored the local variable and parameters of the methods (the program execution stack).

For example, let’s have a class called Dog, which has the properties for name, kind and age. Let’s create a variable dog from this class. This variable is a reference to the object and is in the dynamic memory (heap).

The reference is a variable, which can access objects. The figure below depicts an example reference, which has link to the real object in the heap, and is called with the name dog. One, compare to the variable from primitive (value type), does not contain the real value (i.e. the data of the object), but the address, where one is located in the heap memory:

When we declare one variable from type a particular class, and we do not want the variable to be associated with a specific object, then we assign to it the value null. The reserved word null in the C# language means, that the variable does not point to any object (there is a missing value):

Organizing Classes in Files and Namespaces

In C# the only one limitation regarding the saving of our own custom classes is: they have to be saved in files with file extension .cs. In such a file several classes, structures and other types can be defined. Although it is not a requirement of the compiler, it is recommended every class to be stored in exactly one file, which corresponds to its name, i.e. the class Dog should be saved in a file Dog.cs.

Organizing Classes in Namespaces

As we should know from the chapter "Creating and Using Objects", the namespaces in C# are named group of classes, which are logically connected, without a requirement how they are stored in the file system.

If we want to include in our code namespaces for the operation in our classes, declared in some file or set of files, this should be done by the so named using directives. They are not required, but if they exist, they are on the first lines in the class file, before the declaration of the classes or other types. In the next paragraphs we will understand how they exactly are used.

After the insertion of the used namespaces, the next is the declaration of the namespace of the classes in the file. As we know, there is no requirement to declare classes in a namespace, but it is a good programming technique if we do it, because the class distribution in the namespace is used for better organization of the code and determination of the classes with equal names.

The namespaces contain classes, structure, interfaces and other types of data, and as well other namespaces. An example of nested namespace is System, which contains the namespace Data. The full name of the second namespace is System.Data and one is nested in the namespace System.

The full name of a class in .NET Framework is the class name, preceded by the namespace in which the class is declared, e.g.: <namespace_name>.

<class_name>. By the using reserved word we can use types from certain namespace, without writing the full name, e.g.:

|

using System; … DateTime date; |

Instead of:

|

System.DateTime date; |

One typical declaration sequence, which we should follow when we create custom classes in .cs files, is:

|

// Using directives – optional using <namespace1>; using <namespace2>;

// Namespace definition - optional namespace <namespace_name> { // Class declaration class <first_class_name> { // … Class body … }

// Class declaration class <second_class_name> { // … Class body … }

// …

// Class declaration class <n-th_class_name> { // … Class body … } } |

The declaring of the namespace and the relevant include of it is already explained in the chapter "Creating and Using Objects" and therefore we will not discuss it again.

Before we continue, let’s look into the first line of the previous snippet. Instead include of namespace it is a source code comment. This is not a problem in compilation time, the comments are "removed" from the code and thus the first line is still the including statement.

Encoding of Files and Using of Cyrillic and Unicode

While we are creating a .cs file, in which to declare our classes, it is good to think about its character encoding in the file system.

In the .NET Framework the compiled code is represented in Unicode so it is possible to use characters in our code from alphabets other than Latin. In the next example we use Cyrillic letters for identifiers in Bulgarian language as well as comments in the code, written in Bulgarian (in Cyrillic letters):

|

using System;

public class EncodingTest { // Тестов коментар static int години = 4;

static void Main() { Console.WriteLine("years: " + години); } } |

This code will compile and execute without a problem, but to keep the characters readable in the Visual Studio editor we need to provide an appropriate encoding of the file.

As we know from the "Strings" chapter, some not all characters can be stored in all encodings. If we use non-standard characters such as Chinese, Cyrillic or Arabic letters, we can use UTF-8 or other character encoding that supports these characters. By default Visual Studio uses the default character encoding (system locale) defined in the regional settings in Windows. This might be ISO-8859-1 in U.K. or U.S. and Windows-1251 in Bulgaria.

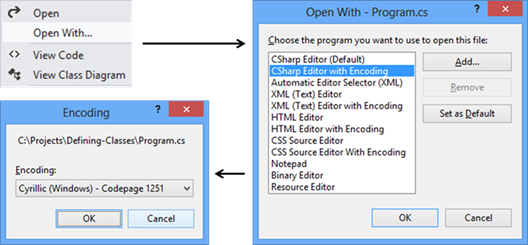

To use a different encoding other than the system’s default encoding in Visual Studio, we need to choose the appropriate encoding of the file when opening it in the editor:

1. From the File menu we choose Open and then File.

2. In the Open File window we click on the option next to the button Open and we choose Open With…

3. From the list in the Open With window we choose an editor with encoding support, for example CSharp Editor with Encoding.

4. Then press [OK].

5. In the window Encoding we choose the appropriate encoding from the dropdown menu Encoding.

6. Then press [OK].

The steps for saving files in the file system with a specific encoding are:

1. From the File menu we choose Save As.

2. In the window Save File As we press the drop-down box next to the button Save and choose Save with Encoding.

3. In Advanced Save Options we select the desired encoding from the list (preferably the universal UTF-8).

4. From the Line Endings we select the desired line ending type.

Although we have the ability to use characters from any non-English alphabet, in .cs files it is highly recommended to write all the identifiers and comments in English, because this way our code will be readable for more people in the world.

Imagine that you live in Germany and you need to type a code written by a Vietnamese person, where the names of all variables and comments are in Vietnamese. You will prefer English, right? Then think about how a developer from Vietnam will handle variables and comments in German.

Modifiers and Access Levels (Visibility)

Let’s revise, from the chapter "Methods” we know that a modifier is a reserved word and with the help of it we add additional information for the compiler and the code related to the modifier.

In C# there are four access modifiers: public, private, protected and internal. The access modifiers can be used only in front the following elements of the class: class declaration, fields, properties and methods.

Modifiers and Access Levels

As we explained, in C# there are four access modifiers – public, private, protected and internal. Based on them we control the access (visibility) to the elements of the class, in front of which they are used. The levels of access in .NET are public, protected, internal, protected internal and private. In this chapter we will review in details only public, private and internal. More about protected and protected internal we will learn in "Object-Oriented Programming Principles".

Access Level "public"

When we use the modifier public in front of some element, we are telling the compiler, that this element can be accessed from every class, no matter from the current project (assembly), from the current namespace. The access level public defines the miss of restrictions regarding the visibility. This access level is the least restricted access level in C#.

Access Level "private"

The access level private is the one, which defines the most restrictive level of visibility of the class and its elements. The modifier private is used to indicate, that the element, to which is issued, cannot be accessed from any other class (except the class, in which it is defined), even if this class exists in the same namespace. This is the default access level, i.e. it is used when there is no access level modifier in front of the respective element of a class (this is true only for elements inside a class).

Access Level "internal"

The modifier internal is used to limit the access to the elements of the class only to files from the same assembly, i.e. the same project in Visual Studio. When we create several projects in Visual Studio, the classes from will be compiled in different assemblies.

Assembly

.NET assemblies are collections of compiled types (classes and other types) and resources, which form a logical unit. Assemblies are stored in a binary file of type .exe or .dll. All types in C# and as general in .NET Framework can reside only inside assemblies. By every compilation of a .NET application one or several assemblies are created by the C# compiler and each assembly is stored inside an .exe or .dll file.

The definition of a class is based on strict syntactical rules:

|

[<access_modifier>] class <class_name> |

When we declare a class, it is mandatory to use the reserved word class. After it must stay the name of the class <class_name>.

Besides the reserved word class and the name of the class, in the declaration of the class can be used several modifiers, e.g. the reviewed until now modifiers.

Class Visibility

Let’s consider two classes – A and B. We say that, class A accesses the elements of class B, if the first class can do one of the following:

1. Creates an object (instance) from class type B.

2. Can access distinct methods and fields in the class B, based on the access level assigned to the particular methods and fields.

There is also another operation, which can be done over the classes, when the visibility allows it. The operation is called inheritance of a class, but we will discuss it later in the chapter Object-Oriented Programming Principles.

As we understood, the access level term means "visibility". If the class A cannot "see" the class B, the access level of the methods and the fields in B does not matter.

The access levels, which an outer class can have, are only public and internal. Inner classes can be defined with other access levels.

Access Level "public"

If we declare a class access modifier as public, we can reach it from every class and from every namespace, regardless of where it exists. It means that every other class can create objects from this type and has access to the methods and the fields of the public class.

Just to know, if we want to use a class with access level public from other namespace, different from the current, we should use the reserved word for including different namespaces using or every time we should write the full name of the class.

Access Level "internal"

If we declare one class with access modifier internal, one will be accessible only from the same namespace. It means that only the classes from the same assembly can create objects from this type class and to have access to the methods and fields (with related access level) of the class. This access level is the default, where it is not used access modifier by the declaration of the class.

If we have two projects in common solution in Visual Studio and we want to use a class from one project into the other one then the referenced class should be declared as public.

Access Level "private"

If we want to be exhaustive, we have to mention that as access modifier for a class can be used the visibility modifier private, but this is related to the term "inner class" (nested class), which we will review in the "Nested Classes" section. Private classes like other private members are accessible only inside the class which defined them.

Body of the Class

By similarity to the methods, after the declaration of the class follows its body, i.e. the part of the class where resides the following programming code:

|

[<access_modifier>] class <class_name> { // … Class body – the code of the class goes here … } |

The body of the class begins with opening curly bracket "{" and ends with closing one – "}". The class always should have a body.

Class Naming Convention

Equal to the methods, for creation of the class names there are the following common standards:

1. The names of the classes begin with capital letter, and the rest of the letters are lower case. If the name of the class consists of several words, every word begins with capital letter, without separator to be used. This is the well-known PascalCase convention.

2. For name of the classes nouns are usually used.

3. It is recommended the name of the class to be in English language.

Here are some example class names, which are following the guidelines:

|

Dog Account Car BufferedReader |

More about the name of the classes we will learn in the chapter "High-Quality Programming Code".

The reserved word this in C# is used to reference the current object, when one is used from method in the same class. This is the object, which method or constructor is called. The reserved word can be deemed as an address (reference), given priory from the language authors, with which we access the elements (fields, methods, constructor) of the own class:

|

this.myField; // access a field in the class this.DoMyMethod(); // access a method in the class this(3, 4); // access a constructor with two int parameters |

Currently, we will not explain the given code above. Later, we will do it in other sections of this chapter, dedicated to the elements of the class (fields, methods, constructors) and as well related to the reserved word this.

Objects describe things from the real world. In order to describe an object, we focus on its characteristics, which are related to the problems solved in our program. These characteristics of the real-world object we will hold in the declaration of the class in special types of variables. These variables, called fields (or member-variables), are holding the state of the object. When we create an object based on certain class definition, the values of the fields are containing the characteristics of the created object (its state). These characteristics have different values different for the different objects.

Until now we have discussed only two types of variables (see "Methods") depending on where they are declared:

1. Local variables – these are the variables declared in the body of some method (or block).

2. Parameters – these are the variables in the list of parameters, which one method can have.

In C# a third type of variable exists, called field or instance variable.

Fields are declared in the body of the class, outside the body of a single method or constructor.

|

Fields are declared in the body of the class but not in the bodies of the methods or the constructors. |

This is a sample code declaring several fields:

|

class SampleClass { int age; long distance; string[] names; Dog myDog; } |

More formal, the declaration of a field is done in the following way:

|

[<modifiers>] <field_type> <field_name>; |

The <field_type> part determinates the type of a given field. This type can be primitive (byte, short, char and so on), an array, or also some class type (e.g. Dog or string).

The <field_name> part is the name of the field. As the name of the normal variables, when we declare the name of the instance-variables, we should obey the rules for naming of identifiers in C# (see chapter "Primitive Types and Variables").

The <modifiers> part is a definition, which describes the access modifiers and as well other modifiers. The last ones are not a mandatory part of the field declaration.

Modifiers and the access modifiers, allowed in the declaration of one field, are explained in chapter "Primitive Types and Variables".

In this chapter, from the other modifiers, which are not based on access levels, and can be used in the declaration of fields, we will discuss static, const and readonly.

Scope

The scope of a class field starts from the line where is declared and ends at the closing bracket of the body of the class.

Initialization during Declaration

When we declare one field it is possible to assign to it an initial value. We do this similarly to an assignment of normal local variable:

|

[<modifiers>] <field_type> <field_name> = <initial_value>; |

Of course, the <initial_value> has to be a type compatible with the field’s type, e.g.:

|

class SampleClass { int age = 5; long distance = 234; // The literal 234 is of integer type

string[] names = new string[] { "Peter", "Martin" }; Dog myDog = new Dog();

// … Other code … } |

Default Values of the Fields

Every time, when we create a new object of a given class, it is allocated memory in the heap for every field from the class. In order this to be done the memory is initialized automatically with the default values for the certain field. The fields, which do not have explicitly a default value in the code, use the default value specified for the .NET type, to which they belong.

This is different for the local variables defined in methods. If a local variable in a method does not have a value assigned, the code will not compile. If a member variable (field) in a class does not have a value assigned, it will be automatically zeroed by the compiler.

|

When an object is created all of the fields are initialized with their respective default values in .NET, except if they are not explicitly initialized with some other value. |

In some languages (as C and C++) the newly created objects are not initialized with default values of theirs data and this creates conditions for hard-to-find errors. The last leads to uncontrolled behavior, where the program sometimes works correctly (when the allocated memory by chance has good values), and sometimes does not work (when the allocated memory does not contain the proper values). In C# and generally in .NET Framework this problem is solved by the default values for each type coming from the framework.

The value of all types is 0 or something similar. For the most used types these values are as the follows:

|

Type of the Field |

Default Value |

|

bool |

false |

|

byte |

0 |

|

char |

'\0' |

|

decimal |

0.0M |

|

double |

0.0D |

|

float |

0.0F |

|

int |

0 |

|

object reference |

null |

For more detailed information you can check chapter "Primitive Types and Variables" and its section about the primitive types and their default values.

For example, if we create a class Dog and we define for it fields name, age and length and check for the gender isMale, without explicitly initializing them, they will be automatically zeroed when we create an object of this class:

|

public class Dog { string name; int age; int length; bool isMale;

static void Main() { Dog dog = new Dog(); Console.WriteLine("Dog's name is: " + dog.name); Console.WriteLine("Dog's age is: " + dog.age); Console.WriteLine("Dog's length is: " + dog.length); Console.WriteLine("Dog is male: " + dog.isMale); } } |

Respectively, when we execute the program we will have as output the following:

|

Dog's name is: Dog's age is: 0 Dog's length is: 0 Dog is male: False |

Automated Initialization of Local Variables and Fields

If we define a local variable in one method, without initializing it, and afterward we try to use it (e.g. printing its value), this will trigger a compilation error, because the local variables are not initialized with default values when they are declared.

|

Unlike fields, local variables are not initialized with default values when they are declared. |

Let’s have look into one example:

|

static void Main() { int notInitializedLocalVariable; Console.WriteLine(notInitializedLocalVariable); } |

If we try to compile, we will receive the following error:

|

Use of unassigned local variable 'notInitializedLocalVariable' |

Custom Default Values

A good programming practice is, when we declare fields in the class, to explicitly initialize them with some default value, even if the default value is zero. This will make our code clearer and easy to read.

One example for such initialization is the modified example class SampleClass from the previous section:

|

class SampleClass { int age = 0; long distance = 0; string[] names = null; Dog myDog = null;

// … Other code … } |

Modifiers "const" and "readonly"

As was explained in the beginning in this section, in the declaration of one field is allowed to use the modifications const and readonly. The fields, declared as const or readonly are called constants. They are used when a certain value is used several times. These values are declared only ones without repetitions. Examples of constants in the .NET Framework are the mathematical constants Math.PI and Math.E, and as well the constants String.Empty and Int32.MaxValue.

Constants Based on "const"

The fields, declared with const, have to be initialized during the de facto declaration and afterwards theirs value cannot be changed. They can be accessed without to create an instance (an object) of the class and they are common for all created objects in our program. Something more, when we compile the code, the places where const fields are referred are replaced with theirs particular values directly without to use the constant variable at all. For this reason the const fields are called compile-time constants, because they are replaced with the value during the compilation process.

Constants Based on "readonly"

The modifier readonly creates fields, which values cannot be changed once they are assigned. Fields, declared as readonly, allow one-time initialization either in the moment of the declaration or in the class constructors. Later theirs values cannot be changed. Because of this reason, the readonly fields are called run-time constants – constants, because their values cannot be changed after assignment and run-time, because this process happens during the execution of the program (in runtime).

Let’s illustrate the foregoing with the following example:

|

public class ConstAndReadOnlyExample { public const double PI = 3.1415926535897932385; public readonly double Size;

public ConstAndReadOnlyExample(int size) { this.Size = size; // Cannot be further modified! }

static void Main() { Console.WriteLine(PI); Console.WriteLine(ConstAndReadOnlyExample.PI); ConstAndReadOnlyExample instance = new ConstAndReadOnlyExample(5); Console.WriteLine(instance.Size);

// Compile-time error: cannot access PI like a field Console.WriteLine(instance.PI);

// Compile-time error: Size is instance field (non-static) Console.WriteLine(ConstAndReadOnlyExample.Size);

// Compile-time error: cannot modify a constant ConstAndReadOnlyExample.PI = 0;

// Compile-time error: cannot modify a readonly field instance.Size = 0; } } |

In chapter "Methods" we have discussed how to declare and use a method. In this section we will revise how we do this and we will focus on some additional features from the process of creating methods. Till now we have used static methods only. Now it is time to start using non-static (instance) methods.

Declaring of Class Method

The declaration of methods is done in the following way:

|

// Method definition [<modifiers>] [<return_type>] <method_name>([<parameters_list>]) { // … Method's body … [<return_statement>]; } |

The mandatory elements for declaration of a method are the type of the return value <return_type>, the name of the method <method_name> and the opening and the closing brackets – "(" and ")".

The parameter list <params_list> is not mandatory. We use it to pass data to the method, which we declare, when this is required.

We know, if the return type <return_type> is void, then <return_statement> can be declared without the return statement. If <return_type> is different from void, the method has to return a result with the help of the reserved word return and an expression, which is from the type <return_type> or a compatible one.

The work, which the method has to do, is situated in the method body, enclosed in curly brackets – "{" and "}".

We already discussed some of the access modifiers that can be used in the declaration of a method in the section "Visibility of Methods and Fields" we will review in details this again.

The static modifier will be explained in depth in the section "Static Classes and Static Members".

Example – Method Declaration

Let’s see the declaration of a method, which sums two values:

|

int Add(int number1, int number2) { int result = number1 + number2; return result; } |

The name of the method is Add and the return value type is int. The parameter list consists of two elements – the variables number1 and number2. Accordingly, the return value is the sum of the two parameters as a result.

Accessing Non-Static Data of the Class

In "Creating and Using Objects", we have discussed how based on the "dot" operator we can access fields and to call the methods of a given class. Now, let’s recall how we use conventional non-static methods of a given class, i.e. the methods do not have the modifier static in theirs declaration.

E.g. let’s have the class Dog with the field age. To print the value of this field we need to create a Dog instance and access the field of this instance via a “dot” notation:

|

public class Dog { int age = 2;

static void Main() { Dog dog = new Dog(); Console.WriteLine("Dog's age is: " + dog.age); } } |

The result will be:

|

Dog's age is: 2 |

Accessing Non-Static Fields from Non-Static Method

The access to the value of one field can be done via the “dot” notation (as in the last example dog.age), or via a method or property. Now, let’s create in the class Dog a method, which will return the value of age:

|

public int GetAge() { return this.age; } |

As we see, to access the value of the age field, inside, from the owner class, we use the reserved word this. We know that the word this is a reference to the current object, in which the method resides. Therefore, in our example, with "return this.age", we say "from the current object (this) take (the use of the operator “dot”), the value of the field age, and return it as result from the method (with the help of the reserved word return). Then, instead from the Main() method to access the values of the field age of the object dog, we simple call the method GetAge():

|

static void Main() { Dog dog = new Dog(); Console.WriteLine("Dog's age is: " + dog.GetAge()); } |

The result of the execution based on the change will be the same.

Formally, the declaration of access to a field in the boundaries of a class is the following:

|

this.<field_name> |

Let’s emphasize, that this access option is possible only from non-static code, i.e. method or block, which is without static modifier.

Except for retrieving of the value of one field, we can use the reserved word this for modification of the field.

E.g., let’s declare a method MakeOlder(), which will be called every year on the date of the birthday of our pet and this method will increment the age with one year:

|

public void MakeOlder() { this.age++; } |

To check if this is correct in the Main() method we add the following lines:

|

// One year later, at the birthday date… dog.MakeOlder(); Console.WriteLine("After one year dog's age is: " + dog.age); |

After the execution of the program, the result is the following:

|

Dog's age is: 2 After one year dog's age is: 3 |

Calling Non-Static Methods

Like the fields, which do not have static modifier in theirs declarations, the methods, which are also non-static, can be called in the body of a class via the reserved word this. This is happening again with the "dot" notation and more specifically with the required arguments (if there are any):

|

this.<method_name>(…) |

For example, let’s create a method PrintAge(), which prints the age of the object from type Dog, and for this purpose calls the method GetAge():

|

public void PrintAge() { int myAge = this.GetAge(); Console.WriteLine("My age is: " + myAge); } |

The first line of the example is indicating that we want to receive the age (the value of the field age) of the current object, using the method GetAge(). This is done via the reserved word this.

|

The access to the non-static elements of a class (fields and methods) is done via the reserved word this and the operator for access – "dot". |

Skip "this" Keyword When Accessing Non-Static Data

When we access the fields of a class or we call its non-static methods, it is possible to omit the reserved word this. Then both methods, which we already declared will be written in this way:

|

public int GetAge() { return age; // The same like this.age }

public void MakeOlder() { age++; // The same like this.age++ } |

The reserved word this is used to indicate explicitly that we want to have access to a non-static field of a class or to call some of its non-static methods. When this explicit clarification is not needed, it can be skipped and directly to access the elements of the class.

Although it is understood clearly, the reserved word this is often used for access to fields in the class, because it helps to make the code easier to read, understand and maintain, by explicitly stating that we access a field and not a local variable.

|

When it is not required explicitly the reserved word this can be skipped when we access the elements of the class. For better readability use this keyword even when not required. |

Hiding Fields with Local Variables

From the section "Declaring Fields" above, we know that the scope of one field starts from the line where the declaration is made to the closing curly bracket of the class. For example let's see the OverlappingScopeTest class:

|

public class OverlappingScopeTest { int myValue = 3;

void PrintMyValue() { Console.WriteLine("My value is: " + myValue); }

static void Main() { OverlappingScopeTest instance = new OverlappingScopeTest(); instance.PrintMyValue(); } } |

This code will have the following result on the console:

|

My value is: 3 |

On the other hand, when we implement the body of one method we have to declare local variables which we will use for the work of the method. As we know, the scope of a local variable begins from the line where it is declared to the closing bracket of the body of the method. For example, let’s add this method to the class OverlappingScopeTest:

|

Int CalculateNewValue(int newValue) { int result = myValue + newValue; return result; } |

In this case, the local variable, which we will use to calculate the new value, is result.

Sometimes the name of the local variable can overlap with the name of some field. In this case there is a collision.

Let’s first look at one example, before we explain what it is about. Let’s modify the method PrintMyValue() in the following way:

|

void PrintMyValue() { int myValue = 5; Console.WriteLine("My value is: " + myValue); } |

If we declare in this way the method, could it be possible to compile this code? And if it is compiled, is it possible to execute it? If it is compiled and executed which value will be printed – the one of the field or the one of the local variable?

After the execution of the Main() method, the result will be:

|

My value is: 5 |

This is so, because C# allows defining local variables, which names match with fields of the class. If this happens, we say that the scope of the local variable overlays the field variable (scope overlapping).

Therefore the scope of the local variable myValue with value 5 overlapped the scope of the field variable in the class. Then, when we print we will get the local variable value.

Despite this, sometimes it is required use the field instead the local variable with the same name. In this case, to retrieve the value of the field, we use the reserved word this. For this purpose we access the field by using the "dot" operator, applied to the reserved word this. In this way, we say deliberately that we want to use the field of the class, and not the local variable with the same name.

Let’s take a look again at our example relate to the printing of the value myValue:

|

void PrintMyValue() { int myValue = 5; Console.WriteLine("My value is: " + this.myValue); } |

This time, after we applied the changes, the result from the call of the method is different:

|

My value is: 3 |

Visibility of Fields and Methods

In the beginning of this chapter we have discussed the generality of the modifiers and the access levels for the elements in one class in C#. Later we have discussed the access level in the declaration for one class.

Now we will discuss the visibility levels of fields and methods in a class. Because the fields and the methods are elements of the class (members) and have similar rules for access levels, we will expose these rules simultaneously.

Differently from the declaration of a class, when we declare fields and methods in the class we can use the four access levels – public, protected, internal and private. The access level protected will not be discussed in this chapter, because it is related to class inheritance and is explained in details in the chapter "Object-Oriented Programming Principles".

Before we continue, let’s revise, if one class A is not visible (does not have access) from other class B, then none of its elements (fields and method) can be accessed from class B.

|

If two classes are not visible one to other, then their members (fields and methods) are not visible also, regardless of what kind of access levels their elements have. |

In the next subsections, to the explanations until now, we will review examples, in which we have two classes (Dog and Kid) and which are visible one to other, i.e. every from the classes can create objects from the other type – the other class and to access its elements depending from the defined access level declared. Here is how the first class Dog looks like:

|

public class Dog { private string name = "Doggy";

public string Name { get { return this.name; } }

public void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); }

public void DoSomething() { this.Bark(); } } |

In addition to the fields and the methods the property Name is used, which just returns the field’s value. We will discuss in details the property concept later, so currently we will just focus on everything else except the properties.

The code of the class Kid looks like this:

|

public class Kid { public void CallTheDog(Dog dog) { Console.WriteLine("Come, " + dog.Name); }

public void WagTheDog(Dog dog) { dog.Bark(); } } |

Currently, all elements (fields and methods) of both classes are declared with access modifier public, but when we discuss the other access modifiers we will change some of them accordingly. What we would like to find is how the change in the access levels of the elements (fields and methods) of the class Dog will be reflected, when the access is made with:

- The own body of the class Dog.

- The body of the class Kid, respectively, taking into account that Kid is in the same namespace (or assembly), in which the Dog class is defined or not.

Access Level "public"

When a method or a value of a class is declared with access level public, the last can be used from other classes, independently from the fact if another class is declared in the same namespace, assembly or outside of it.

Let’s review both type of access to members of a class, which are matched in our classes Dog and Kid:

|

The access to the member of the class is done inside the same class directly (the class refers itself). |

|

|

The access to the member of the class is done via a reference to an object created in the body of another class (the class refers another class). |

When the members of both classes are public, we have the following:

|

Dog.cs |

|

|

|

class Dog { public string name = "Doggy"; public string Name { get { return this.name; } } public void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); } public void DoSomething() { this.Bark(); } } |

|

Kid.cs |

|

|

|

class Kid { public void CallTheDog(Dog dog) { Console.WriteLine("Come, " + dog.name); } public void WagTheDog(Dog dog) { dog.Bark(); } } |

As we can see, we implement without problem the access to the field name and the method Bark() of the class Dog from the body of the same class. Independently, if the namespace of the class Kid is the same as Dog, we can, from its body, access the field name and to call the method Bark() via the “dot” operator, applied to the reference dog of the object from type Dog.

Access Level "internal"

When a member of some class is declared with access level internal, then this element from the class can be accessed from every class in the same assembly (i.e. in the same project in Visual Studio), but not from classes outside it (i.e. from other projects in Visual Studio – from the same solution or from a different solution).

Not that if we have a Visual Studio project, all classes in it are from the same assembly and classes defined in different Visual Studio projects (in the same or in a different solution) are from different assemblies.

Below is the explanation about the access level internal:

|

Dog.cs |

|

|

|

class Dog { internal string name = "Doggy";

public string Name { get { return this.name; } }

internal void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); }

public void DoSomething() { this.Bark(); } } |

Respectively, for the class Kid, we discuss two cases:

- When the class in the same assembly, then the access to the elements of Dog will be allowed, independent of whether the classes are in the same namespace or not:

|

Kid.cs |

|

|

|

class Kid { public void CallTheDog(Dog dog) { Console.WriteLine("Come, " + dog.name); }

public void WagTheDog(Dog dog) { dog.Bark(); } } |

- When the class Kid is external for the assembly, in which Dog is declared, then the access to the field name and the method Bark() will be denied:

|

Kid.cs |

|

|

|

class Kid {

{ Console.WriteLine("Come, " + dog.name); }

{ dog.Bark(); } } |

Actually the access level internal for members of the class Dog is impossible for two reasons: insufficient visibility of the class and insufficient visibility of its members. To allow access from other assembly to the class Dog, one is required to be declared public and in the same time its members to be declared as public. If the class or its members have lower visibility, the access to it from other assemblies is denied (i.e. from other Visual Studio projects which compile to different .dll / .exe file).

If we try to compile the class Kid, when one is external for the assembly, in which the class Dog resides, we will get a compilation error.

Access Level "private"

The access level, which is the most restrictive, is private. The elements of the class, which are declared with access modifier private (or without any, because private is the default one), cannot be accessed outside of the class in which they are declared.

Therefore, if we declare the field name and the method Bark() of the class Dog with access modifier private, there is no problem to access them from the same instance of the class Dog, but access from any other classes is not permitted. If you try to access a private method from external class, a compilation error occur. Below is the figure about the access level private:

|

Dog.cs |

|

|

|

class Dog { private string name = "Doggy";

public string Name { get { return this.name; } }

private void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); }

public void DoSomething() { this.Bark(); } } |

Accessing the name fields from the same class is permitted, but accessing it from a different class (Kid) is restricted:

|

Kid.cs |

|

|

|

class Kid {

{ Console.WriteLine("Come, " + dog.name); }

{ dog.Bark(); } } |

We should know, when we assign access modifier to a filed, one in most of the cases has to be private, because this ensures the highest level of security applied to the field. Respectively, the access and the modification of the value from other classes (if it is required) will be done only via properties or methods. More about this technique we will learn in the section "Properties and Encapsulation of Fields" as well as in the "Encapsulation" section of the chapter "Object-Oriented Programming Principles".

How to Decide Which Access Level to Use?

Before we end up the section regarding visibility of the elements of a class, let’s try something. Let’s define in the class Dog the field name and the method Bark() witch access modifier private. Let’s also declare the method Main() with the following body:

|

public class Dog { private string name = "Doggy";

// …

private void Bark() { Console.WriteLine("wow-wow"); }

// …

static void Main() { Dog myDog = new Dog(); Console.WriteLine("My dog's name is " + myDog.name); myDog.Bark(); } } |

The question is, if the class Dog can compile when we have declared the elements with access modifier private and in the same time is applied a ”dot” notation to myDog in Main()?

The compilation finished successfully. Respectively, the result from the execution of the method Main() which is declared in the class Dog will be the following:

|

My dog's name is Rolf Wow-wow |

Everything works, because the access modifiers for the elements of the class are applied to the class and not to a level objects. Because the variable myDog is defined in the body of the class Dog (where also is situated Main() – the start method of the program), we can access its elements (fields and methods) via “dot” notation, regardless we have declared the access level as private. If we try to do the same in the body of the class Kid, this will be not possible, because the access to private fields from outside class is forbidden.

In object-oriented programming, when creating an object from a given class, it is necessary to call a special method of the class known as a constructor.

What Is a Constructor?

Constructor of a class is a pseudo-method, which does not have a return type, has the name of the class and is called using the keyword new. The task of the constructor is to initialize the memory, allocated for the object, where its fields will be stored (those which are not static ones).

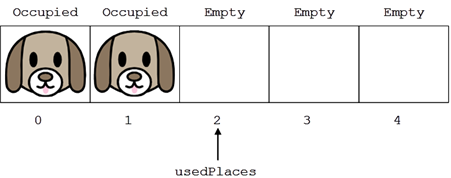

The only one way to call a constructor in C# is through the keyword new. It allocates memory for the new object (in the stack or in the heap, depending on whether the object is a value type or a reference type), resets its fields to zero, calls their constructors (or chain of constructors, formed in succession), and at the end returns a reference to the newly created object.

Consider an example, which will clarify how the constructor works. We know from chapter "Creating and Using Objects" how to create an object:

|

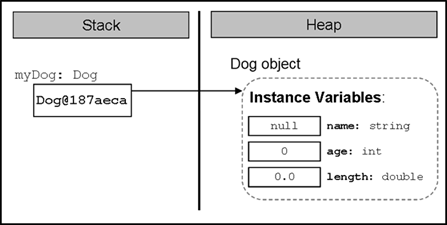

Dog myDog = new Dog(); |

In this case by using the keyword new we call the constructor of the class Dog and by doing this, memory is allocated, needed for the newly created object of the Dog type. When it comes to classes they are allocated in the dynamic memory (in the so called "managed heap").

Let’s follow the process of calling a constructor during the creation of new object step by step.

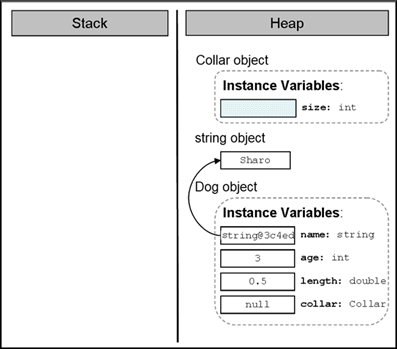

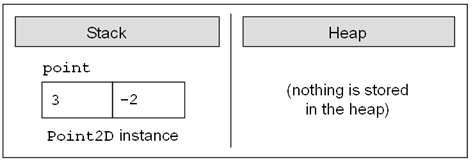

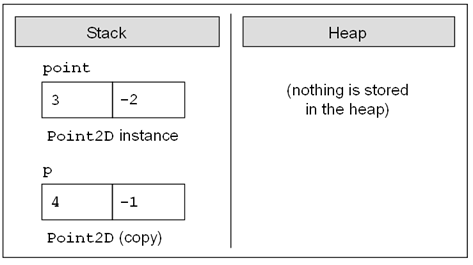

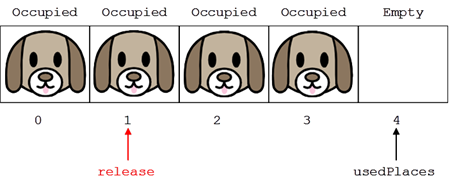

First, memory is allocated for the object:

Next, its fields (if any) are initialized with the default values for their respective types:

If the creation of the new object is successfully completed, the constructor returns a reference to it, which is assigned to the variable myDog, from class type Dog:

Declaring a Constructor

If we have the class Dog, here is how its most simplified constructor (without parameters) will look like:

|

public Dog() { } |

Formally, the declaration of the constructor appears in the following way:

|

[<modifiers>] <class_name>([<parameters_list>]) |

As we already know, the constructors are similar to methods, but they do not have a return type (therefore we called them pseudo-methods).

Constructor’s Name

In C# it is mandatory that the name of every constructor matches the name of the class in which it resides – <class_name>. In the example above the name of the constructor is the same as the name of the class – Dog. We should know that, as with methods, the name of the constructor is always followed by round brackets – "(" and ")".

In (C#) it is not allowed to declare a method whose name matches the name of the class (hence the name of the constructors). If nevertheless, a method is declared with the class name, this will cause a compilation error.

|

public class IllegalMethodExample { // Legal constructor public IllegalMethodExample () { }

// Illegal method private string IllegalMethodExample() { return "I am illegal method!"; } } |

When we try to compile this class the compiler will display the following compilation error message:

|

SampleClass: member names cannot be the same as their enclosing type |

Parameter List

Similar to the methods, if we need extra data to create an object, the constructor gets it through a parameter list – <parameters_list>. In the example constructor of the class Dog there is no need of additional data to create an object of this type and therefore there is no parameter list. More about the parameter list will be explained in one of the later sections –"Declaring a Constructor with Parameters".

Of course, after the declaration of the constructor its body is following, which is like every method body in C#, but generally contains mostly initialization logic, i.e. setting the initial values of the fields of the class.

Modifiers

It is evident that modifiers can be added in the declaration of the constructors – <modifiers>. For modifiers that we know and which are not access modifiers, i.e. const and static, we should know that only const is not allowed to be used in constructors. Later in this chapter, in the "Static Constructors" section we will learn more about the constructors declared with modifier static.

Visibility of the Constructors

Similar to the methods and the fields, the constructors can be declared with levels of visibility: public, protected, internal, protected, internal and private. The access levels protected and protected internal will be explained in chapter "Object-Oriented Programming Principles". The rest of the access levels have the same meaning and behavior as with fields and methods.

Initialization of the Fields in the Constructor

As explained earlier when creating a new object and calling its constructor, a new memory is allocated for the non-static fields of the object of the class and they are initialized with the default values for their types (see the section "Calling a Constructor").

Furthermore, through the constructors we mainly initialize the fields of the class with values set by us and not with the default ones.

E.g., in the examples we discussed so far, the field name of the object from type Dog is always initialized during its declaration:

|

string name = "Axl"; |

Instead of doing this during the declaration of the field, a better programming style is to assign its value in the constructor:

|

public class Dog { private string name;

public Dog() { this.name = "Axl"; }

// … The rest of the class body … } |

Although we initialize the fields in the constructor, some people recommend explicitly assigning their type’s default values during initialization with the purpose of improving the readability of the code, but it is a matter of personal choice:

|

public class Dog { private string name = null;

public Dog() { this.name = "Axl"; }

// … The rest of the class body … } |

Fields Initialization in the Constructor

Let’s see in details what the constructor does after being called and the class fields have been initialized in its body. We know that, when called, it will allocate memory for each field and this memory will be initialized with the default values.

If the fields are of primitive type, then after the default values, we shall assign new values.

In case the fields are from reference type, such as our field name, the constructor will initialize them with null. It will then create the object of the corresponding type, in this case the string "Axl" and at the end a reference will be assigned to the new object in the respective field, in our case the field name.

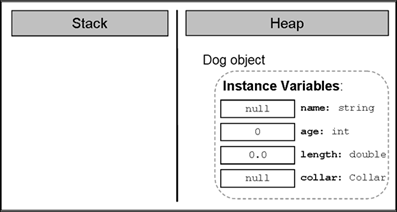

The same will happen if we have other fields, which are not primitive types, and then initialize them in the constructor. E.g. let’s have a class called Collar, which describes a dog’s accessory – Collar:

|

public class Collar { private int size;

public Collar() { } } |

Let our class Dog has a field called collar, which is from type Collar and which is initialized in the constructor of the class:

|

public class Dog { private string name; private int age; private double length; private Collar collar;

public Dog() { this.name = "Axl"; this.age = 3; this.length = 0.5; this.collar = new Collar(); }

static void Main() { Dog myDog = new Dog(); } } |

Representation in the Memory

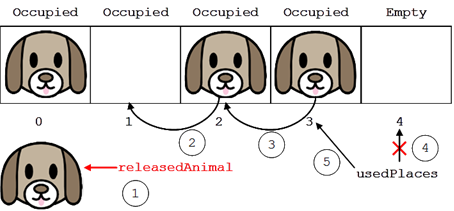

Let’s follow the steps through which the constructor goes, after being called in the Main() method. As we know it will allocate memory in the heap for all the fields and will initialize them with their default values:

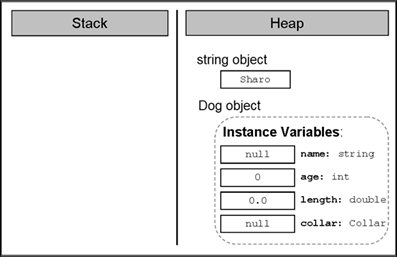

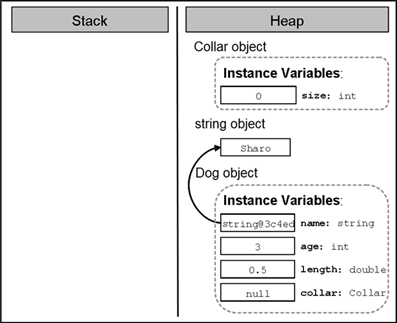

Then, the constructor will have to ensure the creation of the object for the field name (i.e. it will call the constructor of the class string, which will do the work on the string creation):

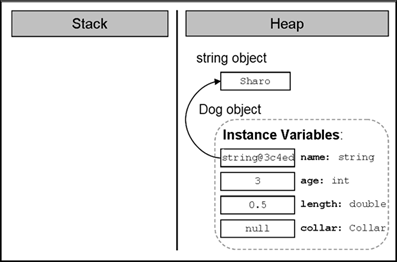

Now the constructor will keep the reference to the new string in the field name:

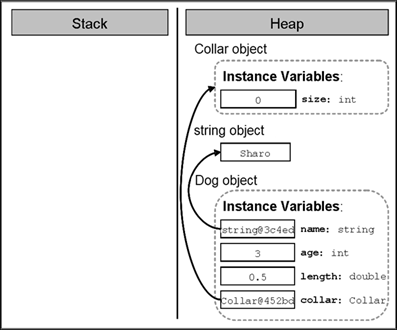

Then is the creation of the object from type Collar. Our constructor (of the class Dog) calls the constructor of the class Collar, which allocates memory for the object:

Next, the constructor will initialize it with the default value for the respective type:

After that the reference to the newly created object, which the constructor of the class Collar returns as a result, will be assigned to the field collar:

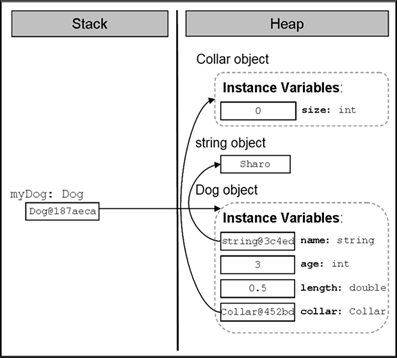

Finally, the reference to the new object from type Dog will be assigned to the local variable myDog in the method Main():

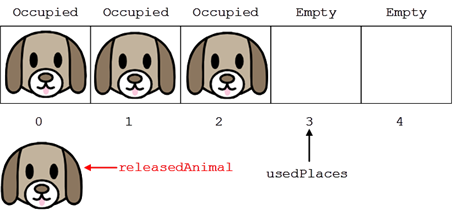

Order of Initialization of the Fields

To avoid confusion, let’s explain the order in which the fields of a class are initialized regardless of whether we have assigned to them values and / or initialized them in the constructor.

First memory is allocated for the respective field in the heap and this memory is initialized with the default value of the field type. E.g. let’s again consider the example with the class Dog:

|

public class Dog { private string name;

public Dog() { Console.WriteLine( "this.name has value of: \"" + this.name + "\""); // … No other code here … } // … Rest of the class body … } |

When we try to create a new object of our class type the console will show:

|

this.name has value of: "" |

After the initialization of the fields with the default value for the respective type, the second step in CLR (Common Language Runtime) is to assign a value to the field if such has been set when declaring the field.

So, if we change the line in the class Dog, where we declare the field name, it will first be initialized with the value null and then it will be assigned the value "Rex".

|

private string name = "Rex"; |

Respectively, for every creation of a new object of the class:

|

static void Main() { Dog dog = new Dog(); } |

The following will be printed:

|

this.name has value of: "Rex" |

Only after these two steps of initializing the fields of the class (default value initialization and possibly the value set by the programmer during the declaration of the field) the constructor of the class is called. At this time, the fields get the values, which are set in the body of the constructor.

Declaring a Constructor with Parameters

In the previous section, we saw how we can set values to the fields, other than the default values. Very often, however, during the declaration of the constructor, we don’t know what values the various fields will take. To tackle this problem, the required information, similar to the methods with parameters, the fields are assigned the values, given to them in the body of the constructor. For example:

|

public Dog(string dogName, int dogAge, double dogLength) { name = dogName; age = dogAge; length = dogLength; collar = new Collar(); } |

Similarly, the call of a constructor with parameters is done in the same way as the call of method with parameters – the required values are supplied as a list, the elements of which are separated with commas:

|

{ Dog myDog = new Dog("Moby", 2, 0.4); // Passing parameters

Console.WriteLine("My dog " + myDog.name + " is " + myDog.age + " year(s) old. " + " and it has length: " + myDog.length + " m."); } |

The result of the execution of this Main() method is the following:

|

My dog Moby is 2 year(s) old. It has length: 0.4 m. |

There is no limitation for the number of the constructors of a class in C#. The only requirement is that they differ in their signature (what signature is we already explained in chapter "Methods").

Scope of Parameters of the Constructor

By analogy with the scope of the variables in the parameter list of a method, the variables in the parameter list of one constructor have a scope from the opening bracket of the constructor to the closing bracket, i.e. throughout the body of the constructor.

Very often, when we declare a constructor with parameters it is possible to name the variables from the parameter list with the same names as the names of the fields, which are going to be initialized. Let’s, for example, consider the constructor of the class Dog:

|

public Dog(string name, int age, double length) { name = name; age = age; length = length; collar = new Collar(); } |

Let’s compile and execute the Main() method declared a little bit above:

|

My dog is 0 year(s) old. It has length: 0 m |

Strange result, isn’t it? In fact this result is not so awkward. The explanation is the following: the scope, in which the variables from the list of the constructor parameters are acting, overlaps the scope of acting of the fields with the same names in the constructor. Thus, we do not assign any value to the fields because in practice we have no access to them. For example, instead of assigning the variable value to the field age, we assign the value of the variable age to the variable itself:

|

age = age; |

As we saw from the section "Hiding Fields with Local Variables", to avoid this problem we should access the field, to which we want to assign a value, using the keyword this:

|

public Dog(string name, int age, double length) { this.name = name; this.age = age; this.length = length; this.collar = new Collar(); } |

Now, assuming we execute again the Main() method:

|

static void Main() { Dog myDog = new Dog("Moby", 2, 0.4);

Console.WriteLine("My dog " + myDog.name + " is " + myDog.age + " year(s) old. " + " and it has length: " + myDog.length + " m"); } |

The result will be exactly what we expect it to be:

|

My dog Moby is 2 year(s) old. It has length: 0.4 m |

Constructor with Variable Number of Arguments

Similar to methods with variable number of arguments, discussed in chapter "Methods", constructors can also be declared with a parameter for a variable number of arguments. The rules for declaring and calling constructors with a variable number of arguments are the same as the ones, described for declaring and calling with the methods:

1. When we declare a constructor with variable number of arguments, we must use the reserved word params, and then insert the type of the parameters, followed by square parentheses. Finally the name of the array follows, in which array the arguments used for the calling of the method are stored. For example for whole number arguments we can use params int[] numbers.

2. It is allowed for the constructor with a variable number of arguments to have other parameters too in the parameter list.

3. The parameter for the variable number of arguments must be the last in the parameter list of the constructor.

Consider a sample declaration of a constructor of a class, which describes a lecture:

|

public Lecture(string subject, params string[] studentsNames) { // … Initialization of the instance variables … } |

The first parameter in the declaration is the name of the subject of the lecture and the next parameter represents a variable number of arguments – the names of the students. Here is how a sample object of this class would be constructed:

|

Lecture lecture = new Lecture("Biology", "Peter", "Mike", "Steven"); |

Accordingly, as the first parameter is the name of the subject – "Biology", and all the rest arguments – the names of the attending students.

As we saw, we can declare constructors with parameters. This gives us a possibility to declare constructors with different signatures (number and order of the parameters) with the purpose of providing convenience to those who will create objects from our class. Creating constructors with different signatures is called constructor overloading.

Consider, for example, the class Dog. We can declare different constructors:

|

// No parameters public Dog() { this.name = "Axl"; this.age = 1; this.length = 0.3; this.collar = new Collar(); }

// One parameter public Dog(string name) { this.name = name; this.age = 1; this.length = 0.3; this.collar = new Collar(); }

// Two parameters public Dog(string name, int age) { this.name = name; this.age = age; this.length = 0.3; this.collar = new Collar(); }

// Three parameters public Dog(string name, int age, double length) { this.name = name; this.age = age; this.length = length; this.collar = new Collar(); }

// Four parameters public Dog(string name, int age, double length, Collar collar) { this.name = name; this.age = age; this.length = length; this.collar = collar; } |

Reusing Constructors

In our last example we saw that, depending on the needs for creating objects of our class, we can declare different variants of the constructors. It is easy to notice that a large part of the constructor code is repeated. This leads us to the question whether there is an alternative way for a constructor, which is already doing an initializing, to be reused by the others to perform the same initialization. On the other hand, at the beginning of the chapter it was mentioned that a constructor cannot be called in the manner in which the methods are called but by the keyword new. There should be a way – otherwise a lot of code will be repeated unnecessarily.

In C# a mechanism exists through which one constructor can call another one declared in the same class. This is done again with the keyword this, but used in another syntax structure in declaring the constructors:

|

[<modifiers>] <class_name>([<parameters_list_1>]) : this([<parameters_list_2>]) |

To the well-known form of declaring a constructor (the first line of the declaration above), we can add a colon, followed by the keyword this, followed by parentheses. If the constructor we want to call has parameters, in the brackets we need to add a list of parameters parameters_list_2 to be supplied.

Here is how the code from the section about constructor overloading would look like, in which instead of repeating the initialization of each of the fields, we will call the constructors declared in the same class:

|

// No parameters public Dog() : this("Axl") // Constructor call { // More code could be added here }

// One parameter public Dog(string name) : this(name, 1) // Constructor call { }

// Two parameters public Dog(string name, int age) : this(name, age, 0.3) // Constructor call { }

// Three parameters public Dog(string name, int age, double length) : this(name, age, length, new Collar()) // Constructor call { }

// Four parameters public Dog(string name, int age, double length, Collar collar) { this.name = name; this.age = age; this.length = length; this.collar = collar; } |

As indicated by comments in the first constructor in the example above, if necessary, in addition to calling any of the other constructors with certain parameters, every constructor can add into its body a code, which performs additional initializations or other actions.

Default Constructor

Consider the following question – what happens if we don’t declare a constructor in our class? How can we create objects from this type?

As it often happens, when a class is without a single constructor, this issue is resolved by C#. When we do not declare any constructors, the compiler will create one for us and this one will be used to create objects such as our class. This constructor is called default implicit constructor and it will not have any parameters and will be empty (i.e. it will not do anything in addition to the default zeroing of the object fields).

|

When we do not declare any constructor in a given class, the compiler will create one, known as a default implicit constructor. |

For example, let’s declare the class Collar, without declaring any constructor in it:

|

public class Collar { private int size;

public int Size { get { return size; } } } |

Although we do not have an explicitly declared constructor without parameters, we can create objects of this class in the following way:

|

Collar collar = new Collar(); |

The default parameterless constructor looks the following way:

|

<access_level> <class_name>() { } |

We should know that the default constructor is always named like the class <class_name>, and its parameter list is always empty as well as its body. The compiler simply adds one if there is no constructor in the class. The default constructor is usually public (except for some very specific situations, where it is protected).

|

The default constructor is always without parameters. |

To make sure that the default constructor is always without parameters let’s try to call the default constructor by setting it with parameters:

|

Collar collar = new Collar(5); |

The compiler will display the following error message:

|

'Collar' does not contain a constructor that takes 1 arguments |

How the Default Constructor Works?

As we can guess, the only thing the default constructor will do when creating objects of our class, is to zero the fields of the class. For example, if in the class Collar we have not declared any constructor and we create an object from it, and later we try to print the value in the field size:

|

static void Main() { Collar collar = new Collar(); Console.WriteLine("Collar's size is: " + collar.Size); } |

The result will be:

|

Collar's size is: 0 |

We see that the value saved in the field size of the object collar is just the default value of the whole number type – int.

When a Default Constructor Will Not Be Created?

We have to know that if we declare at least one constructor in a given class then the compiler will not create a default constructor.

To investigate this, consider the following example:

|

public Collar(int size) : this() { this.size = size; } |

Let this be the only constructor in the class Collar. We try to call a constructor without parameters in it, hoping that the compiler will have created a default parameterless constructor for us. After we try to compile, we will find out that what we are trying to do is not possible. The compiler will show the following error:

|

'Collar' does not contain a constructor that takes 0 arguments |

The rule about the default implicit parameterless constructor is:

|

If we declare at least one constructor in a given class, the compiler will not create a default constructor for us. |

Difference between a Default Constructor and a Constructor without Parameters

Before we finish this section for the constructors, we will clarify something very important:

|

Although the default constructor and the one without parameters are similar in signature, they are completely different. |

The difference is that the default implicit constructor is created by the compiler, if we do not declare any constructor in our class, and the constructor without parameters is declared by us.

Moreover, as explained earlier, the default constructor will always have access level protected or public, depending on the access modifier of the class, while the level of access of the constructor without parameters all depends on us – we define it.

In the world of object-oriented programming there is an element of the classes called property, which is somewhere between a field and a method and serves to better protect the state in the class. In some languages for object-oriented programming, like C#, Delphi / Pascal, Visual Basic, Python, JavaScript, and others, the properties are a part of the language, i.e. there is a special mechanism to declare and use them. Other languages like Java do not support the property concept and for this purpose the programmers should declare a pair of methods (for reading and modifying the property) to provide this functionality.

Properties in C# – Introduction by Example

Using the properties is a good and proven practice and an important part of the concepts for object-oriented programming. The creation of a property in programming is done by declaring two methods – one for access (reading) and one for modifying (setting) the value of the respective property.

Consider an example. Assume we have again class Dog, which describes a dog. A characteristic of a dog is, for example, its color. The access to the property "color" of a dog and its corresponding modification can be accomplished in the following way:

|

// Getting (reading) a property string colorName = dogInstance.Color;

// Setting (modifying) a property dogInstance.Color = "black"; |