Chapter 8. Numeral Systems

In this chapter we will take a look at working with different numeral systems and how numbers are represented in them. We will pay more attention to how numbers are represented in decimal, binary and hexadecimal numeral systems, since they are most widely used in computers and programming. We will also explain the different ways for encoding numeral data in computers – signed or unsigned integers and the different types of real numbers.

Content

- Video

- Presentation

- Mind Maps

- In This Chapter

- History in a Nutshell

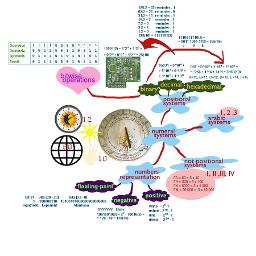

- Numeral Systems

- Representation of Numbers

- Exercises

- Solutions and Guidelines

- Discussion Forum

Video

Presentation

Mind Maps

Different numeral systems have been used since the ancient times. This claim is supported by the fact that in ancient Egypt people used sun dials, which measure time with the help of numeral systems. Most historians believe that ancient Egyptians are the first civilization, which divided the day into smaller parts. They accomplished this by using the first sun dials, which were nothing more than a simple pole stuck in the ground, oriented by the length and direction of the shadow.

Later a better sundial was invented, which looked like the letter T and divided the time between sunrise and sunset into 12 parts. This proves the use of the duodecimal system in ancient Egypt, the importance of the number 12 is usually related to the fact that moon cycles in a single year are 12 or the number of phalanxes found in the fingers of one hand (four in each finger, excluding the thumb).

In modern times, the decimal system is the most widely spread numeral system. Maybe this is due to the fact that it enables people to count by using the fingers on their hands.

Ancient civilizations divided the day into smaller parts by using different numeral systems – duodecimal and sexagesimal with bases 12 and 60 respectively. Greek astronomers such as Hipparchus used astronomical approaches, which were earlier used by the Babylonians in Mesopotamia. The Babylonians did astronomical calculations using the sexagesimal system, which they had inherited from the Sumerians, who had developed it on their own around 2000 B.C. It is not known exactly why the number 60 was chosen for a base of the numeral system but it is important to note that this system is very appropriate for the representation of fractions, because the number 60 is the smallest number that can be divided by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20 and 30 without a remainder.

Applications of the Sexagesimal Numeral System

The sexagesimal system is still used today for measuring angles, geographical coordinates and time. It still finds application on the watch dial and the sphere of the geographical globe. The sexagesimal system was used by Eratosthenes for dividing a circumference into 60 parts in order to create an early system of geographical latitudes, made up from horizontal lines passing through places well known in the past.

One century after Eratosthenes, Hipparchus standardized these lines by making them parallel and conformable to the geometry of the Earth. He introduced a system of geographical longitude lines, which included 360 degrees and respectively passed from north to south and pole to pole. In the book "Almagest" (150 A.D.), Claudius Ptolemy further developed Hipparchus’ studies by dividing the 360 degrees of geographical latitude and longitude into other smaller parts. He divided each of the degrees into 60 equal parts, each of which was later divided again into 60 smaller and equal parts. The parts created by the division were called partes minutiae primae, or "first minute" and respectively partes minutiae secundae, or "second minute". These parts are still used today and are called "minutes" and "seconds" respectively.

Short Summary

We took a short historical trip through the millennia, which helped us learn that numeral systems were created, used and developed as far back as the Sumerians. The presented facts explain why a day contains (only) 24 hours, the hour has 60 minutes and the minute has 60 seconds. This is a result of the fact that the ancient Egyptians divided the day after they had started using the duodecimal numeral system. The division of hours and minutes into 60 equal parts is a result of the work of ancient Greek astronomers, who did their calculations using the sexagesimal numeral system, which was created by the Sumerians and used by the Babylonians.

So far we have taken a look at the history of numeral systems. Let’s now take a detailed look at what they really are and what is their role in computing.

What Are Numeral Systems?

Numeral systems are a way of representing numbers by a finite type-set of graphical signs called digits. We must add to them the rules for depicting numbers. The characters, which are used to depict numbers in a given numeral system, can be perceived as that system’s alphabet.

During the different stages of the development of human civilization, various numeral systems had gained popularity. We must note that today the most widely spread one is the Arabic numeral system. It uses the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, as its alphabet. (An interesting fact is that the depiction of Arabic numerals in modern times is different from the ten digits mentioned above but in spite of all they are still referred to the same numeral system – the decimal one).

Beside an alphabet, every numeral system has a base. The base is a number equal to the different digits used by the system for depicting the numbers in it. For example, the Arabic numeral system is decimal because it has 10 digits. A random number can be chosen as a base, which has an absolute value different than 1 and 0. It can also be a real or a complex number with a sign.

A practical question we can ask is: which is the best numeral system that we should use? To answer it, we must decide what the optimal way to depict a number (the digit count in the number) is and the number of digits the given numeral system uses – its base. Mathematically it can be proven that the best ratio between the length of depiction and the number of used digits is accomplished by using Euler's number (e = 2,718281828), which is the base of natural logarithms.

Working in a system with such base e is extremely inconvenient and impractical because that number cannot be represented as a ratio of two natural numbers. This gives us grounds to conclude that the optimal base of a numeral system is either 2 or 3.

Although the number 3 is closer to the Neper number, it is unsuitable for technical implementation. Because of that the binary numeral system is the only one suitable for practical use and it is used in the modern computers and electronic devices.

Positional Numeral Systems

A positional numeral system is a system, in which the position of the digits is significant for the value of the number. This means that the value of the digits in the number is not strictly defined and depends on which position the given digit is. For example, in the number 351 the digit 1 has a value of 1, while in the number 1024 it has a value of 1000. We must note that the bases of the numeral systems are applicable only with positional numeral systems. In a positional numeral system the number A(p) = (a(n)a(n-1)…a(0),a(-1)a(-2)…a(-k)) can be represented in the following way:

In this sum Tm has the meaning of a weight factor for the mth digit of the number. In most cases Tm = Pm, which means that:

Formed using the sum above, the number A(p) is respectively made up from its whole part (a(n)a(n-1)…a(0)) and its fraction (a(-1)a(-2)…a(-k)), where every a belongs to the multitude of the natural numbers M={0, 1, 2, …, p-1}. We can easily see that in positional numeral systems the value of each digit is the-base-of-the-system times bigger than the one before it (the digit to the right, which is the lower-order digit). As a direct result from this we must add one to the left (higher-order) digit, if we need to note a digit in the current digit that is bigger than the base. The systems with bases of 2, 8, 10 and 16 have become wide spread in computing devices. In the table below we can see their notation of the numbers from 0 to 15:

|

Octal |

Decimal |

Hexadecimal |

|

|

0000 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0001 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

0010 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

0011 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

0100 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

0101 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

0110 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

0111 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

|

1000 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

|

1001 |

11 |

9 |

9 |

|

1010 |

12 |

10 |

A |

|

1011 |

13 |

11 |

B |

|

1100 |

14 |

12 |

C |

|

1101 |

15 |

13 |

D |

|

1110 |

16 |

14 |

E |

|

1111 |

17 |

15 |

F |

Non-Positional Numeral Systems

Besides the positional numeral systems, there are also non-positional numeral systems, in which the value of each digit is a constant and does not strictly depend on its position in the number. Such numeral systems are the Roman and Greek numeral systems. All non-positional numeral systems have a common drawback – the notation of big numbers in them is very inefficient. As a result of this drawback, they have gained only limited use. This could often lead to inaccuracy when determining the value of numbers. We will take a very brief look at the Roman and Greek numeral systems.

Roman Numeral System

The Roman numeral system uses sequences of the following symbols to represent the numbers:

|

Roman Digit |

Decimal Value |

|

I |

1 |

|

V |

5 |

|

X |

10 |

|

L |

50 |

|

C |

100 |

|

D |

500 |

|

M |

1000 |

As we have already mentioned, in this numeral system the position of the digit has no significance for the value of the number and for determining the value, the following rules are applied:

1. If two consecutively represented Roman digits are in such order that the value of the first one is bigger or equal to the value of the second one, their values are added. Example:

The number III=3, but the number MMD=2500.

2. If two consecutively represented roman digits are in increasing order of their values, they are subtracted. Example:

The number IX=9, the number MXL=1040, but the number MXXIV=1024.

Greek Numeral System

The Greek numeral system is a decimal system, in which a grouping of fives is done. It uses the following digits:

|

Greek Digit |

Decimal Value |

|

Ι |

1 |

|

Г |

5 |

|

Δ |

10 |

|

Η |

100 |

|

Χ |

1,000 |

|

Μ |

10,000 |

As we can see in the table, one is represented with a vertical line, five with the letter Г, and the powers of 10 with the first letter of the corresponding Greek word.

Here are some examples of numbers in this system:

- ΓΔ = 50 = 5 x 10

- ΓH = 500 = 5 x 100

- ΓX = 5000 = 5 x 1,000

- ΓM = 50,000 = 5 x 10,000

The Binary Numeral System – Foundation of Computing Technology

The binary numeral system is the system, which is used to represent and process numbers in modern computing machines. The main reason it is so widely spread is explained with the fact that devices with two stable states are very simple to implement and the production costs of binary arithmetic devices are very low.

The binary digits 0 and 1 can be easily represented in the computing machines as "current" and "no current", or as "+5V" and "-5V".

Along with its advantages, the binary system for number notation in computers has its drawbacks, too. One of its biggest practical flaws is that numbers represented in binary numeral system are very long, meaning they have a large number of bits. This makes it inconvenient for direct use by humans. To avoid this disadvantage, systems with larger bases are used in practice.

Decimal Numbers

Numbers represented in the decimal numeral system, are given in a primal appearance, meaning that they are easy to be understood by humans. This numeral system has the number 10 for a base. The numbers represented in it are ordered by the powers of the number 10. The lowest-order digit (first from right to left) of the decimal numbers is used to represent the ones (100=1), the next one to represent the tens (101=10), the next one to represent the hundreds (102=100), and so on. In other words – every following digit is ten times bigger than the one preceding it. The sum of the separate digits determines the value of the number. We will take the number 95031 as an example, which can be represented in the decimal numeral system as:

95031 = (9×104) + (5×103) + (0×102) + (3×101) + (1×100)

Represented that way, the number 95031 is presented in a natural way for humans because the principles of the decimal numeral system have been accepted as fundamental for people.

|

The discussed approaches are valid for the other numeral systems, too. They have the same logical setting but are applied to a system with a different base. The last statement is true for the binary and hexadecimal numeral systems, which we will discuss in details in a little bit. |

Binary Numbers

The numbers represented in the binary numeral system are represented in a secondary aspect – which means that they are easy to be understood by the computing machine. They are a bit harder to be understood by people. To represent a binary number, the binary numeral system is used, which has the number 2 for a base. The numbers represented in it are ordered by the powers of two. Only the digits 0 and 1 are used for their notation.

Usually, when a number is represented in a numeral system other than decimal, the numeral system’s base is added as an index in brackets next to the number. For example, with this notation 1110(2) we indicate a number in the binary numeral system. If no numeral system is explicitly specified, it is accepted that the number is in the decimal system. The number is pronounced by reading its digits in sequence from left to right (we read from the highest-order to the lowest-order bit).

Like with decimal numbers, each binary number being looked at from right to left is represented by a power of the number 2 in the respected sequence. The lowest-order position in a binary number corresponds to the zero power (20=1), the second position corresponds to 2 to the first power (21=2), the third position corresponds to 2 to the second power (22=4), and so on. If the number is 8 bits long, the last bit is 2 to the seventh power (27=128). If the number has 16 bits, the last bit is 2 to the fifteenth power. By using 8 binary digits (0 or 1) we can represent a total of 256 numbers, because 28=256. By using 16 binary digits we can represent a total of 65536 numbers, because 216=65536.

Let’s look at some examples of numbers in the binary numeral system. Take, for example, the decimal number 148. It is composed of three digits: 1, 4 and 8, and it corresponds to the following binary number:

10010100(2)

148 = (1×27) + (1×24) + (1×22)

The full notation of the number is depicted in the following table:

|

Number |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Power |

27 |

26 |

25 |

24 |

23 |

22 |

21 |

20 |

|

Value |

1×27= 128 |

0×26= 0 |

0×25= 0 |

1×24= 16 |

0×23= 0 |

1×22= 4 |

0×21= 0 |

0×20= 0 |

The sequence of eight zeros or ones represents one byte, an ordinary eight bit binary number. All numbers from 0 to 255 including can be represented in a single byte. In most cases this is not enough; as a result several consecutive bytes can be used to represent a big number. Two bytes form the so called "machine word" (word), which corresponds to 16 bits (in 16-bit computing machines). Besides it, computing machines use the so called double word or dword, corresponding to 32 bits.

|

If a binary number ends in 0 it is even, if it ends in 1 it is odd. |

Converting From Binary to Decimal Numeral System

When turning from binary to decimal numeral system, we do a conversion of a binary number to a decimal number. Every number can be converted from one numeral system to another by doing a sequence of operations that are possible in both numeral systems. As we have already mentioned, numbers in the binary system consist of binary digits, which are ordered by the powers of 2. Let’s take the number 11001(2). Converting into decimal is done by calculating the following sum:

11001(2) = 1×24 + 1×23 + 0×22 + 0×21 + 1×20 =

= 16(10) + 8(10) + 1(10) = 25(10)

From this follows that 11001(2) = 25(10)

In other words – every single binary digit is multiplied by 2 raised to the power of the position it is in. In the end all of the numbers resulting from the binary digits are added up to get the decimal value of the binary number.

Another method of conversion exists, known as the Horner Scheme. When using it, we multiply the left most digit by 2 and add it to the one to its right. We multiply this result by two and the neighboring digit (one to the right) is added. This is repeated until all the digits in the number have been exhausted and we add the last digit without multiplying it. Here is an example:

1001(2) = ((1 × 2 + 0) × 2 + 0) × 2 + 1 = 2 × 2 × 2 + 1 = 9

Converting from Decimal to Binary Numeral System

When transitioning from decimal to binary numeral system, we convert a decimal number into a binary one. To accomplish this, we divide it by 2 with a remainder. This is how we get the quotient and the remainder, which is separated.

Let’s use the number 148 again as an example. We do an integer division by the base we want to convert to (in this case it is 2). After that using the remainders of the division (they will always be either zero or one), we represent the converted number. We continue dividing until we get a zero quotient. Here is an example:

148:2=74 with remainder 0;

74:2=37 with remainder 0;

37:2=18 with remainder 1;

18:2=9 with remainder 0;

9:2=4 with remainder 1;

4:2=2 with remainder 0;

2:2=1 with remainder 0;

1:2=0 with remainder 1;

After we are done with the division, we represent the remainders in reverse order as follows:

10010100

i.e. 148(10) = 10010100 (2)

Operations with Binary Numbers

The arithmetical rules of addition, subtraction and multiplication are valid for a single digit of binary numbers:

0 + 0 = 0 0 - 0 = 0 0 × 0 = 0

1 + 0 = 1 1 - 0 = 1 1 × 0 = 0

0 + 1 = 1 1 - 1 = 0 0 × 1 = 0

1 + 1 = 10 10 - 1 = 1 1 × 1 = 1

In addition, with binary numbers we can also do logical operations such as logical multiplication (conjunction), logical addition (disjunction) and the sum of modulo two (exclusive or).

We must also note that when we are doing arithmetic operations with multi-order numbers we must take into account the connection between the separate orders by transfer or loan, when doing addition or subtraction respectively. Let’s take a look at some details regarding bitwise operators.

Bitwise "and"

The bitwise AND operator can be used for checking the value of a given bit in a number. For example, if we want to check if a given number is even (we check if the lowest-order bit is 1):

10111011 AND 00000001 = 00000001

The result is 1, which means that the number is odd (if the result was 0 the number would be even).

In C# the bitwise "and" is represented with & and is used like this:

|

int result = integer1 & integer2; |

Bitwise "or"

The bitwise OR operator can be used if we want, for example, to "raise" a given bit to 1:

10111011 OR 00000100 = 10111111

Bitwise "or" in C# is represented with | and is used like this:

|

int result = integer1 | integer2; |

Bitwise "exclusive or"

The bitwise operator XOR – every binary digit is processed separately, and when we have a 0 in the second operand, the corresponding value of the bit in the first operand is copied in the result. At every position that has a value of 1 in the second operand, we reverse the value of the corresponding position in the first operand and represent it in the result:

10111011 XOR 01010101 = 11101110

In C# the notation of the "exclusive or" operator is ^:

|

int result = integer1 ^ integer2; |

Bitwise Negation

The bitwise operator NOT – this is a unary operator, which means that it is applied to a single operand. What it does is to reverse every bit of the given binary number to its opposite value:

NOT 10111011 = 01000100

In C# the bitwise negation is represented with ~:

|

int result = ~integer1; |

Hexadecimal Numbers

With hexadecimal numbers we have the number 16 for a system base, which implies the use of 16 digits to represent all possible values from 0 to 15 inclusive. As we have already shown in one of the tables in the previous sections, for notating numbers in the hexadecimal system, we use the digits from 0 to 9 and the Latin numbers from A to F. Each of them has the corresponding value:

A=10, B=11, C=12, D=13, E=14, F=15

We can give the following example for hexadecimal numbers: D2, 1F2F1, D1E and so on.

Transition to decimal system is done by multiplying the value of the right most digit by 160, the next one to the left by 161, the next one to the left by 162 and so on, and adding them all up in the end. Example:

D1E(16) = E*160 + 1*161 + D*162 = 14*1 + 1*16 + 13*256 = 3358(10).

Transition from decimal to hexadecimal numeral system is done by dividing the decimal number by 16 and taking the remainders in reverse order. Example:

3358 / 16 = 209 + remainder 14 (E)

209 / 16 = 13 + remainder 1 (1)

13 / 16 = 0 + remainder 13 (D)

We take the remainders in reverse order and get the number D1E(16).

Fast Transition from Binary to Hexadecimal Numbers

The fast conversion from binary to hexadecimal numbers can be quickly and easily done by dividing the binary number into groups of four bits (splitting it into half-bytes). If the number of digits is not divisible by four, leading zeros in the highest-orders are added. After the division and the eventual addition of zeros, all the groups are replaced with their corresponding digits. Here is an example:

Let’s look at the following: 1110011110(2).

1. We divide it into half-bytes and add the leading zeros

Example: 0011 1001 1110.

2. We replace every half-byte with the corresponding hexadecimal digit and we get 39E(16).

Therefore 1110011110 (2) = 39E(16).

Numeral Systems – Summary

As a summary, we will formulate again in a short but clear manner the algorithms used for transitioning from one positional numeral system to another:

- Transitioning from a decimal to a k-based numeral system is done by consecutively dividing the decimal to the base of the k system and the remainders (their corresponding digit in the k based system) are accumulated in reverse order.

- Transitioning from a k-based numeral system to decimal is done by multiplying the last digit of the k-based number by k0, the one before it by k1, the next one by k2 and so on, and the products are the added up.

- Transitioning from a k-based numeral system to a p-based numeral system is done by intermediately converting to the decimal system (excluding hexadecimal and binary numeral systems).

- Transitioning from a binary to hexadecimal numeral system and back is done by converting each sequence of 4 binary bits into its corresponding hexadecimal number and vice versa.

Binary code is used to store data in the operating memory of computing machines. Depending on the type of data we want to store (strings, integers or real numbers with an integral and fractal part) information is represented in a particular manner. It is determined by the data type.

Even a programmer using a high level language must know how the data is allocated in the operating memory of the machine. This is also relevant to the cases when the data is stored on an external carrier, because when it is processed, it will be situated in the operating memory.

In the current section we will take a look at the different ways to present and process different types of data. In general they are based on the concepts of bit, byte and machine word.

Bit is a binary unit of information with a value of either 0 or 1.

Information in the memory is grouped in sequences of 8 bits, which form a single byte.

For an arithmetic device to process the data, it must be presented in the memory by a set number of bytes (2, 4 or 8), which form a machine word. These are concepts, which every programmer must know and understand.

Representing Integer Numbers in the Memory

One of the things we have not discussed so far is the sign of numbers. Integers can be represented in the memory in two ways: with a sign or without a sign. When numbers are represented with a sign, a signed order is introduced. It is the highest-order and has the value of 1 for negative numbers and the value of 0 for positive numbers. The rest of the orders are informational and only represent (contain) the value of the number. In the case of a number without a sign, all bits are used to represent its value.

Unsigned Integers

For unsigned integers 1, 2, 4 or 8 bytes are allocated in the memory. Depending on the number of bytes used in the notation of a given number, different scopes of representation with variable size are formed. Through n bytes all integers in the range [0, 2n-1] can be represented. The following table shows the range of the values of unsigned integers:

|

Number of bytes for representing the number in the memory |

Range |

|

|

Notation with order |

Regular notation |

|

|

1 |

0 ÷ 28-1 |

0 ÷ 255 |

|

2 |

0 ÷ 216-1 |

0 ÷ 65,535 |

|

4 |

0 ÷ 232-1 |

0 ÷ 4,294,967,295 |

|

8 |

0 ÷ 264-1 |

0 ÷ 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 |

We will give as an example a single-byte and a double-byte representation of the number 158, whose binary notation is the following 10011110(2):

1. Representation with 1 byte:

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

2. Representation with 2 bytes:

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

For negative numbers 1, 2, 4 or 8 bytes are allocated in the memory of the computer, while the highest-order (the left most bit) has a signature meaning and carries the information about the sign of the number. As we have already mentioned, when the signature bit has a value of 1, the number is negative, otherwise it is positive.

The next table shows the range of the values of the signed integer numbers in the computer according to the number of bytes used for their notation:

|

Number of bytes for representing the number in the memory |

Rank |

|

|

Notation with order |

Regular notation |

|

|

1 |

-27 ÷ 27-1 |

-128 ÷ 127 |

|

2 |

-215 ÷ 215-1 |

-32,768 ÷ 32,767 |

|

4 |

-231 ÷ 231-1 |

-2,147,483,648 ÷ 2,147,483,647 |

|

8 |

-263 ÷ 263-1 |

-9,223,372,036,854,775,808 ÷ |

To encode negative numbers, straight, reversed and additional code is used. In all these three notations signed integers are within the range: [-2n-1, 2n-1-1]. Positive numbers are always represented in the same way and the straight, reversed and additional code all coincide for them.

Straight code (signed magnitude) is the simplest representation of the number. The highest-order bit carries the sign and the rest of the bits hold the absolute value of the number. Here are some examples:

The number 3 in signed magnitude is represented as an eight-bit-long number 00000011.

The number -3 in signed magnitude is represented in an eight-bit-long number as 10000011.

Reversed code (one’s complement) is formed from the signed magnitude of the number by inversion (replacing all ones with zeros and vice-versa). This code is not convenient for the arithmetical operations addition and subtraction because it is executed in a different way if subtraction is necessary. Moreover the sign carrying bits need to be processed separately from the information carrying ones. This drawback is avoided by using additional code, which instead of subtraction implements addition with a negative number. The latter is depicted by its addition, i.e. the difference between 2n and the number itself. Example:

The number -127 in signed magnitude is represented as 1 1111111 and in one’s complement as 1 0000000.

The number 3 in signed magnitude is represented as 0 0000011, and in one’s complement looks like 0 1111100.

Additional code (two’s complement) is a number in reversed code to which one is added (through addition). Example:

The number -127 is represented with additional code as 1 0000001.

In the Binary Coded Decimal, also known as BCD code, in one byte two decimal digits are recorded. This is achieved by encoding a single decimal digit in each half-byte. Numbers presented in this way can be packed, which means that they can be represented in a packed format. If we represent a single decimal digit in one byte we get a non-packed format.

Modern microprocessors use one or several of the discussed codes to present negative numbers, the most widespread method is using two’s complement.

Integer Types in C#

In C# there are eight integer data types either signed or unsigned. Depending on the amount of bytes allocated for each type, different value ranges are determined. Here are descriptions of the types:

|

Type |

Size |

Range |

Type in .NET Framework |

|

sbyte |

8 bits |

-128 ÷ 127 |

System.SByte |

|

byte |

8 bits |

0 ÷ 255 |

System.Byte |

|

short |

16 bits |

-32,768 ÷ 32,767 |

System.Int16 |

|

ushort |

16 bits |

0 ÷ 65,535 |

System.UInt16 |

|

int |

32 bits |

-2,147,483,648 ÷ 2,147,483,647 |

System.Int32 |

|

uint |

32 bits |

0 ÷ 4,294,967,295 |

System.UInt32 |

|

long |

64 bits |

–9,223,372,036,854,775,808 ÷ 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 |

System.Int64 |

|

ulong |

64 bits |

0 ÷ 18,446,744,073,709,551,615 |

System.UInt64 |

We will take a brief look at the most used ones. The most commonly used integer type is int. It is represented as a 32-bit number with two’s complement and takes a value in the range [-231, 231-1]. Variables of this type are most frequently used to operate loops, index arrays and other integer calculations. In the following table an example of a variable of the type int is being declared:

|

int integerValue = 25; int integerHexValue = 0x002A; int y = Convert.ToInt32("1001", 2); // Converts binary to int |

The type long is the largest signed integer type in C#. It has a size of 64 bits (8 bytes). When giving value to the variables of type long the Latin letters "l" or "L" are placed at the end of the integer literal. Placed at that position, this modifier signifies that the literal has a value of the type long. This is done because by default all integer literals are of the type int. In the next example, we declare and give 64-bit value to variables of type long:

|

long longValue = 9223372036854775807L; long newLongValue = 932145699054323689l; |

An important condition is not to exceed the range of numbers that can be represented in the used type. However, C# offers the ability to control what happens when an overflow occurs. This is done via the checked and unchecked blocks. The first are used when the application needs to throw an exception (of the type System.OverflowException) in case that the range of the variable is exceeded. The following programming code does exactly that:

|

checked { int a = int.MaxValue; a = a + 1; Console.WriteLine(a); } |

In case the fragment is in an unchecked block, an exception will not be thrown and the output result will be wrong:

|

-2147483648 |

In case these blocks are not used, the C# compiler works in unchecked mode by default.

C# includes unsigned types, which can be useful when a larger range is needed for the variables in the scope of the positive numbers. Below are some examples for declaring variables without a sign. We should pay attention to the suffixes of ulong (all combinations of U, L, u, l).

|

byte count = 50; ushort pixels = 62872; uint points = 4139276850; // or 4139276850u, 4139276850U ulong y = 18446744073709551615; // or UL, ul, Ul, uL, Lu, lU |

Big-Endian and Little-Endian Representation

There are two ways for ordering bytes in the memory when representing integers longer than one byte:

- Little-Endian (LE) – bytes are ordered from left to right from the lowest-order to the highest. This representation is used in the Intel x86 and Intel x64 microprocessor architecture.

- Big-Endian (BE) – bytes are ordered from left to right starting with the highest-order and ending with the lowest. This representation is used in the PowerPC, SPARC and ARM microprocessor architecture.

Here is an example: the number A8B6EA72(16) is presented in both byte orders in the following way:

There are some classes in C# that offer the opportunity to define which order standard to be used. This is important for operations like sending / receiving streams of information over the internet or other types of communication between devices made by different standards. The field IsLittleEndian of the BitConverter class for example shows what mode the class is working in and how it stores data on the current computer architecture.

Representing Real Floating-Point Numbers

Real numbers consist of a whole and fraction parts. In computers, they are represented as floating-point numbers. Actually this representation comes from the Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic (IEEE 754), adopted by the leading microprocessor manufacturers. Most hardware platforms and programming languages allow or require the calculations to be done according to the requirements of this standard. The standard defines:

- Arithmetical formats: a set of binary and decimal data with a floating-point, which consists of a finite number of digits.

- Exchange formats: encoding (bit sequences), which can be used for data exchange in an effective and compact form.

- Rounding algorithms: methods, which are used for rounding up numbers during calculations.

- Operations: arithmetic and other operations of the arithmetic formats.

- Exceptions: they are signals for extraordinary events such as division by zero, overflowing and others.

According to the IEEE-754 standard a random real number R can be presented in the following way:

R = M * qp

where M is the mantissa of the number, p is the order (exponent), and q accordingly is the base of the numeral system the number is in. The mantissa must be a positive or negative common fraction |M|<1, and the exponent – a positive or negative integer.

In the mentioned method of representation of numbers, every floating-point number will have the following summarized format ±0,M*q±p.

When notating numbers in the floating-point format using the binary numeral system in particular, we will have R = M * 2p. In this representation of real numbers in the computer memory, when we change the exponent, the decimal point in the mantissa moves ("floats"). The floating-point representation format has a semi-logarithmic form. It is depicted in the following figure:

Representing Floating-Point Numbers – Example

Let’s give an example of how a floating-point number is represented in the memory. We want to write the number -21.15625 in 32-bit (single precision) floating-point format according to the IEEE-754 standard. In this format, 23 bits are used for the mantissa, 8 bits for the exponent and 1 bit for the sign. The notation of the number is as follows:

The sign of the number is negative, which means that the mantissa has a negative sign:

S = -1

The exponent has a value of 4 (represented with a shifted order):

p = (20 + 21 + 27) - 127 = (1+2+128) – 127 = 4

For transitioning to the real value we subtract 127 from the additional code because we are working with 8 bits (127 = 27-1) starting from the zero position.

The mantissa has the following value (without taking the sign into account):

M = 1 + 2-2 + 2-4 + 2-7 + 2-9 =

= 1 + 0.25 + 0.0625 + 0.0078125 + 0.001953125 =

= 1.322265625

We should note that we added a one, which was missing from the binary notation of the mantissa. We did it because the mantissa is always normalized and starts with a one by default.

The value of the number is calculated using the formula R = M * 2p, which in our example looks like the following:

R = -1,3222656 * 24 = -1,322265625 * 16 = -21,1562496 ≈ -21,15625

Mantissa Normalization

To use the order grid more fully, the mantissa must contain a one in its highest-power order. Every mantissa fulfilling this condition is called normalized. In the IEEE-754 standard, the one in the whole part of the mantissa is by default, meaning the mantissa is always a number between 1 and 2.

If during the calculations a result that does not fulfill this condition is reached, it means that the normalization is violated. This requires the normalization of the number prior to its further processing, and for this purpose the decimal point in the mantissa is moved and the corresponding order change is made.

The Float and Double Types in C#

In C# we have at our disposal two types, which can represent floating-point numbers. The float type is a 32-bit real number with a floating-point and it is accepted to be called single precision floating-point number. The double is a 64-bit real number with a floating-point and it is accepted that it has a double precision floating-point. These real data types and the arithmetic operations with them correspond to the specification outlined by the IEEE 754-1985 standard. In the following table are presented the most important characteristics of the two types:

|

Type |

Size |

Range |

Significant Digits |

Type in .NET Framework |

|

float |

32 bits |

±1.5 × 10−45 ÷ ±3.4 × 1038 |

7 |

System.Single |

|

double |

64 bits |

±5.0 × 10−324 ÷ ±1.7 × 10308 |

15-16 |

System.Double |

In the float type we have a mantissa, which contains 7 significant digits, while in the double type it stores 15-16 significant digits. The remaining bits are used for specifying the sign of the mantissa and the value of the exponent. The double type, aside from the larger number of significant digits, also has a larger exponent, which means that it has a larger scope of the values it can assume. Here is an example how to declare variables of the float and double types:

|

float total = 5.0f; float result = 5.0f; double sum = 10.0; double div = 35.4 / 3.0; double x = 5d; |

The suffixes placed after the numbers on the right side of the equation, serve the purpose of specifying what type the number should be treated as (f for float, d for double). In this case they are in place because by default 5.0 will be interpreted as a double and 5 – as an int.

|

In C#, floating-point numbers literals by default are of the double type. |

Integers and floating-point numbers can both be present in a given expression. In that case, the integer variables are converted to floating-point variables and the result is defined according to the following rules:

1. If any of the floating-point types is a double, the result will be double (or bool).

2. If there is no double type in the expression, the result is float (or bool).

Many of the mathematical operations can yield results, which have no specific numerical value, like the value "+/- infinity" or NaN (which means "Not a Number"), these values are not numbers. Here is an example:

|

double d = 0; Console.WriteLine(d); Console.WriteLine(1/d); Console.WriteLine(-1/d); Console.WriteLine(d/d); |

If we execute it we get the following result:

|

0.0 Infinity -Infinity NaN |

If we execute the code above using int instead of double, we will receive a System.DivideByZeroException, because integer division by 0 is not an allowed operation.

Errors When Using Floating-Point Numbers

Floating-point numbers (presented according to the IEEE 754 standard) are very convenient for calculations in physics, where very big numbers are used (with several hundred digits) and also numbers that are very close to zero (with hundreds of digits after the decimal point before the first significant digit). When working with these numbers, the IEEE 754 format is exceptionally convenient because it keeps the number’s order in the exponent and the mantissa is only used to store the significant digits. In 64-bit floating-point numbers accuracy of 15-16 digits, as well as exponents displacing the decimal point with 300 positions left or right can be achieved.

Unfortunately not every real number has an exact representation in the IEEE 754 format, because not each number can be presented as a polynomial of a finite number of addends, which are negative powers of two. This is fully valid even for numbers, which are used daily for the simplest financial calculations. For example the number 0.1 represented as a 32-bit floating-point value is presented as 0.099999994. If the appropriate rounding is used, the number can be accepted as 0.1, but the error can be accumulated and cause serious deviations, especially in financial calculations. For example when adding up 1000 items with a unit price of 0.1 EUR each, we should get a sum of 100 EUR but if we use a 32-bit floating-point numbers for the calculations the result will be 99.99905. Here is C# example in action, which proves the errors caused by the inaccurate presentation of decimal real numbers in the binary numeral system:

|

float sum = 0f; for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) { sum += 0.1f; } Console.WriteLine("Sum = {0}", sum); // Sum = 99.99905 |

We can easily see the errors in such calculations if we execute the example or modify it to get even more striking errors.

Precision of Floating-Point Numbers

The accuracy of the results from floating-point calculations depends on the following parameters:

1. Precision of the number representation.

2. Precision of the used number methods.

3. Value of the errors resulting from rounding up, etc.

Calculations with them can be inaccurate because they are represented in the memory with some kind of precision. Let’s look at the following code fragment as an example:

|

double sum = 0.0; for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) { sum += 0.1; } Console.WriteLine("{0:r}", sum); Console.WriteLine(sum); |

During the execution, in the loop we add the value 1/10 to the variable sum. When calling the WriteLine() method, we use the round-trip format specifier "{0:r}" to print the exact (not rounded) value contained in the variable, and after that we print the same value without specifying a format. We expect that when we execute the program we will get 1.0 as a result but in reality, when rounding is turned off, the program returns a value very close to the correct one but still different:

|

0.99999999999999989 1 |

As we can see in the example, by default, when printing floating-point numbers in .NET Framework, they are rounded, which seemingly reduces the errors of their inaccurate notation in the IEEE 754 format. The result of the calculation above is obviously wrong but after the rounding it looks correct. However, if we add 0.1 a several thousand times, the error will accumulate and the rounding will not be able to compensate it.

The reason for the wrong answer in the example is that the number 0.1 does not have an exact representation in the double type and it has to be rounded. Let’s replace double with float:

|

float sum = 0.0f; for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) { sum += 0.1f; } Console.WriteLine("{0:r}", sum); |

If we execute the code above, we will get an entirely different sum:

|

1.00000012 |

Again the reason for this is rounding.

If we investigate why the program yields these results, we will see that the number 0.1 of the float type is represented in the following manner:

All this looks correct except for the mantissa, which has a value slightly bigger than 1.6, not exactly 1.6 because this number cannot be presented as sum of the negative powers of 2. If we have to be very precise, the value of the mantissa is 1 + 1 / 2 + 1 / 16 + 1 / 32 + 1 / 256 + 1 / 512 + 1 / 4096 + 1 / 8192 + 1 / 65536 + 1 / 131072 + 1 / 1048576 + 1 / 2097152 + 1 / 8388608 ≈ 1.60000002384185791015625 ≈ 1.6. Thus the number 0.1 presented in the IEE 754 is slightly more than 1.6 × 2-4 and the error occurs not during the addition but before that, when 0.1 is recorded in the float type.

Double and Float types have a field called Epsilon, which is a constant, and it contains the smallest value larger than zero, which can be represented by an instance of System.Single or System.Double respectively. Each value smaller than Epsilon is considered to be equal to 0. For example, if we compare two numbers, which are different after all, but their difference is smaller than Epsilon, they will be considered equal.

The Decimal Type

The System.Decimal type in .NET Framework uses decimal floating-point arithmetic and 128-bit precision, which is very suitable for big numbers and precise financial calculations. Here are some characteristics of the decimal type:

|

Type |

Size |

Range |

Significant numbers |

Type in .NET framework |

|

decimal |

128 bits |

±1.0 × 10−28 ÷ ±7.9 × 1028 |

28-29 |

System.Decimal |

Unlike the floating-point numbers, the decimal type retains its precision for all decimal number in its range. The secret to this excellent precision when working with decimal numbers lies in the fact that the internal representation of the mantissa is not in the binary system but in the decimal one. The exponent is also a power of 10, not 2. This enables numbers to be represented precisely, without them being converted to the binary numeral system.

Because the float and double types and the operations on them are implementer by the arithmetic coprocessor, which is part of all modern computer microprocessors, and decimal is implemented by the software in .NET CLR, it is tens of times slower than double, but is irreplaceable for the execution of financial calculations.

In case our target is to assign a given literal to variable of type decimal, we need to use the suffixes m or M. For example:

|

decimal calc = 20.4m; decimal result = 5.0M; |

Let’s use decimal instead of float / double in the example from before:

|

decimal sum = 0.0m; for (int i = 1; i <= 10000000; i++) { sum += 0.0000001m; } Console.WriteLine(sum); |

This time the result is exactly what we expected:

|

1.0000000 |

Even though the decimal type has a higher precision than the floating-point types, it has a smaller value range and, for example, it cannot be used to represent the following value 1e-50. As a result, an overflow may occur when converting from floating-point numbers to decimal.

Character Data (Strings)

Character (text) data in computing is text, encoded using a sequence of bytes. There are different encoding schemes used to encode text data. Most of them encode one character in one byte or in a sequence of several bytes. Such encoding schemes are ASCII, Windows-1251, UTF-8 and UTF-16.

The ASCII encoding scheme compares the unique number of the letters from the Latin alphabet and some other symbols and special characters and writes them in a single byte. The ASCII standard contains a total of 127 characters, each of which is written in one byte. A text, written as a sequence of bytes according to the ASCII standard, cannot contain Cyrillic or characters from other alphabets such as the Arabian, Korean and Chinese ones.

Like the ASCII standard, the Windows-1251 encoding scheme compares the unique number of the letters in the Latin alphabet, Cyrillic and some other symbols and specialized characters and writes them in one byte. The Windows-1251 encoding defines the numbers of 256 characters – exactly as many as the different values that can be written in one byte. A text written according to the Windows-1251 standard can contain only Cyrillic and Latin letters, Arabian, Indian or Chinese are not supported.

The UTF-8 encoding is completely different. All characters in the Unicode standard – the letters and symbols used in all widely spread languages in the world (Cyrillic, Latin, Arabian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and many other languages and writing systems) – can be encoded in it. The UTF-8 encoding contains over half a million symbols. In the UTF-8 encoding, the more commonly used symbols are encoded in 1 byte (Latin letters and digits for example), the second most commonly used symbols are coded in 2 bytes (Cyrillic letters for example), and the ones that are used even more rarely are coded in 3 or 4 bytes (like the Chinese, Japanese and Korean alphabet).

The UTF-16 encoding, like UTF-8 can depict text of all commonly used languages and writing systems, described in the Unicode standard. In UTF-16, every symbol is written in 16 bits (2 bytes) and some of the more rarely used symbols are presented as a sequence of two 16-bit values.

Presenting a Sequence of Characters

Character sequences can be presented in several ways. The most common method for writing text in the memory is to write in 2 or 4 bytes its length, followed by a sequence of bytes, which presents the text itself in some sort of encoding (for example Windows-1251 or UTF-8).

Another, less common method of writing texts in the memory, typical for the C language, represents texts as a sequence of characters, usually coded in 1 byte, followed by a special ending character, most frequently a 0. When using this method, the length of the text saved at a given position in the memory is not known in advance. This is considered a disadvantage in many situations.

Char Type

The char type in the C# language is a 16-bit value, in which a single Unicode character or part of it is coded. In most alphabets (for example the ones used by all European languages) one letter is written in a single 16-bit value, and thus it is assumed that a variable of the char type represents a single character. Here is an example:

|

char ch = 'A'; Console.WriteLine(ch); |

String Type

The string type in C# holds text, encoded in UTF-16. A single string in C# consists of 4 bytes length and a sequence of characters written as 16-bit values of the char type. The string type can store texts written in all widespread alphabets and human writing systems – Latin, Cyrillic, Chinese, Japanese, Arabian and many, many others. Here is an example of the usage of the string:

|

string str = "Example"; Console.WriteLine(str); |

1. Convert the numbers 151, 35, 43, 251, 1023 and 1024 to the binary numeral system.

2. Convert the number 1111010110011110(2) to hexadecimal and decimal numeral systems.

3. Convert the hexadecimal numbers FA, 2A3E, FFFF, 5A0E9 to binary and decimal numeral systems.

4. Write a program that converts a decimal number to binary one.

5. Write a program that converts a binary number to decimal one.

6. Write a program that converts a decimal number to hexadecimal one.

7. Write a program that converts a hexadecimal number to decimal one.

8. Write a program that converts a hexadecimal number to binary one.

9. Write a program that converts a binary number to hexadecimal one.

10. Write a program that converts a binary number to decimal using the Horner scheme.

11. Write a program that converts Roman digits to Arabic ones.

12. Write a program that converts Arabic digits to Roman ones.

13. Write a program that by given N, S, D (2 ≤ S, D ≤ 16) converts the number N from an S-based numeral system to a D based numeral system.

14. Try adding up 50,000,000 times the number 0.000001. Use a loop and addition (not direct multiplication). Try it with float and double and after that with decimal. Do you notice the huge difference in the results and speed of calculation? Explain what happens.

15. * Write a program that prints the value of the mantissa, the sign of the mantissa and exponent in float numbers (32-bit numbers with a floating-point according to the IEEE 754 standard). Example: for the number -27.25 should be printed: sign = 1, exponent = 10000011, mantissa = 10110100000000000000000.

1. Use the methods for conversion from one numeral system to another. You can check your results with the help of the Windows built-in calculator, which supports numeral systems in "Programmer" mode. The results are: 10010111, 100011, 101011, 11111011, 1111111111 and 10000000000.

2. Like the previous exercise. Result: F59E(16) and 62878(10).

3. Like the previous exercise. The results are: FA(16) = 250(10) = 11111010(2), 2A3E(16) = 10814(10) = 10101000111110(2), FFFF(16) = 65535(10) = 1111111111111111(2) and 5A0E9(16) = 368873(10) = 1011010000011101001(2).

4. The rule is "divide by 2 and concatenate the remainders in reversed order". For division with a remainder we use the % operator. You can cheat by invoking Convert.ToString(numDecimal, 2).

5. Start with a sum of 0. Multiply the right-most bit with 1 and add it to the sum. Multiply the next bit on the left by 2 and add it to the sum. Multiply the next bit on the left by 4, the next by 8 and so on. You can cheat by invoking Convert.ToInt32(binaryNumAsString, 2).

6. The rule is "divide by the base of the system (16) and concatenate the remainders in reversed order". A logic that gets a hexadecimal digit (0…F) by decimal number (0…15) should also be implemented. You can cheat by invoking num.ToString("X").

7. Start with a sum of 0. Multiply the right-most digit with 1 and add it to the sum. Multiply the next digit to the left by 16 and add it to the sum. Multiply the next digit by 16*16, the next by 16*16*16 and so on. You can cheat by invoking Convert.ToInt32(hexNumAsString, 16).

8. Use the fast method for transitioning between hexadecimal and binary numeral system (each hexadecimal digit turns to 4 binary bits).

9. Use the fast method for transitioning from binary to hexadecimal numeral system (each 4 binary bits correspond to a hexadecimal digit).

10. Directly apply the Horner scheme.

11. Scan the digits of the Roman number from left to right and add them up to a sum, which is initialized with a 0. When processing each Roman digit, take it with a positive or negative sign, depending on the digit after it (whether it has a bigger or smaller decimal value).

12. Take a look at the numbers from 1 to 9 and their corresponding Roman representation with the digits "I", "V" and "X":

1 -> I

2 -> II

3 -> III

4 -> IV

5 -> V

6 -> VI

7 -> VII

8 -> VIII

9 -> IX

We have exactly the same correspondence for the numbers 10, 20, …, 90 with their Roman representation "X", "L" and "C". The same is valid for the numbers 100, 200, …, 900 and their Roman representation with "C", "D" and "M" and so on.

We are now ready to convert the number N into the Roman numeral system. It must be in the range [1…3999], otherwise we should report an error. First we separate the thousands (N / 1000) and replace them with their Roman counterpart. After that we separate the hundreds (N / 100) % 10) and separate them with their Roman counterpart and so on.

13. You can convert first from S-based system to decimal number and then from decimal number to D-based system.

14. If you execute the calculations correctly, you will get 32.00 (for float), 49.9999999657788 (for double) and 50.00 (for decimal) respectively. The differences come from the fact that 0.000001 has no exact representation as float and double. You may notice also that adding decimal values is at least 10 times slower than adding double values.

15. Use the special method for conversion of single precision floating-point numbers to a sequence of 4 bytes: System.BitConverter.GetBytes(

<float>). Then use bitwise operations (shifting and bit masks) to extract the sign, mantissa and exponent following the IEEE 754 standard.

Discussion Forum

Comment the book and the tasks in the : forum of the Software Academy.

Tags: binary, book, C#, C# book, decimal, English, free, hexadecimal numeral systems, Nakov, numeral systems, programming, read online, Representation of Numbers, working with different numeral systems2 responses to “Chapter 8. Numeral Systems”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

![clip_image002[15] clip_image002[15]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image00215_thumb.png)

![clip_image004[10] clip_image004[10]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image00410_thumb.png)

![clip_image007[13] clip_image007[13]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image00713_thumb.png)

![clip_image009[10] clip_image009[10]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image00910_thumb.png)

![clip_image011[10] clip_image011[10]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image01110_thumb.png)

![clip_image013[8] clip_image013[8]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image0138_thumb.png)

[…] Chapter 8. Numeral Systems […]

Excellent. Thank you for this wonderful free resource. I really appreciate your hard work.