Chapter 5. Conditional Statements

In this chapter we will cover the conditional statements in C#, which we can use to execute different actions depending on a given condition. We will explain the syntax of the conditional operators if and if-else with suitable examples and explain the practical application of the operator for selection switch-case.

We will focus on the best practices to be followed in order to achieve a better programming style when using nested or other types of conditional statements.

Content

- Video

- Presentation

- Mind Maps

- In This Chapter

- Comparison Operators and Boolean Expressions

- Conditional Statements "if" and "if-else"

- Conditional Statement "switch-case"

- Exercises

- Solutions and Guidelines

- Demonstrations (source code)

- Discussion Forum

Video

Presentation

Mind Maps

Comparison Operators and Boolean Expressions

In the following section we will recall the basic comparison operators in the C# language. They are important, because we use them to describe conditions in our conditional statements.

Comparison Operators

There are several comparisons operators in C#, which are used to compare pairs of integers, floating-point numbers, characters, strings and other types:

|

Operator |

Action |

|

== |

Equal to |

|

!= |

Not equal to |

|

> |

Greater than |

|

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

|

< |

Less than |

|

<= |

Less than or equal to |

Comparison operators can be used to compare expressions such as two numbers, two numerical expressions, or a number and a variable. The result of the comparison is a Boolean value (true or false).

Let’s look at an example of using comparisons:

|

int weight = 700; Console.WriteLine(weight >= 500); // True

char gender = 'm'; Console.WriteLine(gender <= 'f'); // False

double colorWaveLength = 1.630; Console.WriteLine(colorWaveLength > 1.621); // True

int a = 5; int b = 7; bool condition = (b > a) && (a + b < a * b); Console.WriteLine(condition); // True

Console.WriteLine('B' == 'A' + 1); // True |

In the sample code we perform a comparison between numbers and between characters. The numbers are compared by size while characters are compared by their lexicographical order (the operation uses the Unicode numbers for the corresponding characters).

As seen in the example, the type char behaves like a number and can be subtracted, added and compared to numbers freely. However, this should be used cautiously as it could make the code difficult to read and understand.

By running the example we will produce the following output:

|

True False True True True |

In C# several types of data that can be compared:

- numbers (int, long, float, double, ushort, decimal, …)

- characters (char)

- Booleans (bool)

- References to objects, also known as object pointers (string, object, arrays and others)

Every comparison can affect two numbers, two bool values, or two object references. It is allowed to compare expressions of different types, like an integer with a floating-point number for example. However, not every pair of data types can be compared directly. For example, we cannot compare a string with a number.

Comparison of Integers and Characters

When comparing integers and characters, we directly compare their binary representation in memory i.e. we compare their values. For example, if we compare two numbers of type int, we will compare the values of their respective series of 4 bytes. Here is one example for integer and character comparisons:

|

Console.WriteLine("char 'a' == 'a'? " + ('a' == 'a')); // True Console.WriteLine("char 'a' == 'b'? " + ('a' == 'b')); // False Console.WriteLine("5 != 6? " + (5 != 6)); // True Console.WriteLine("5.0 == 5L? " + (5.0 == 5L)); // True Console.WriteLine("true == false? " + (true == false)); // False |

The result of the example is as follows:

|

char 'a' == 'a'? True char 'a' == 'b'? False 5 != 6? True 5.0 == 5L? True true == false? False |

Comparison of References to Objects

In .NET Framework there are reference data types that do not contain their value (unlike the value types), but contain the address of the memory in the heap where their value is located. Strings, arrays and classes are such types. They behave like a pointer to some value and can have the value null, i.e. no value. When comparing reference type variables, we compare the addresses they hold, i.e. we check whether they point to the same location in the memory, i.e. to the same object.

Two object pointers (references) can refer to the same object or to different objects, or one of them can point to nowhere (to have null value). In the following example we create two variables that point to the same value (object) in the heap.

|

string str = "beer"; string anotherStr = str; |

After executing the source code above, the two variables str and anotherStr will point to the same object (string with value "beer"), which is located at some address in the heap (managed heap).

We can check whether the variables point to the same object with the comparison operator (==). For most reference types this operator does not compare the content of the objects but rather checks if they point at the same location in memory, i.e. if they are one and the same object. The size comparisons (<, >, <= and >=) are not applicable for object type variables.

The following example illustrates the comparison of references to objects:

|

string str = "beer"; string anotherStr = str; string thirdStr = "be" + 'e' + 'r'; Console.WriteLine("str = {0}", str); Console.WriteLine("anotherStr = {0}", anotherStr); Console.WriteLine("thirdStr = {0}", thirdStr); Console.WriteLine(str == anotherStr); // True - same object Console.WriteLine(str == thirdStr); // True - equal objects Console.WriteLine((object)str == (object)anotherStr); // True Console.WriteLine((object)str == (object)thirdStr); // False |

If we execute the sample code, we will get the following result:

|

str = beer anotherStr = beer thirdStr = beer True True True False |

Because the strings used in the example (instances of the class System.String, defined by the keyword string in C#) are of reference type, their values are set as objects in the heap. The two objects str and thirdStr have equal values, but are different objects, located at separate addresses in the memory. The variable anotherStr is also reference type and gets the address (the reference) of str, i.e. points to the existing object str. So by the comparison of the variables str and anotherStr, it appears that they are one and the same object and are equal. The result of the comparison between str and thirdStr is also equality, because the operator == compares the strings by value and not by address (a very useful exception to the rule for comparison by address). However, if we convert the three variables to objects and then compare them, we will get a comparison of the addresses in the heap where their values are located and the result will be different.

This above example shows that the operator == has a special behavior when comparing strings, but for the rest of the reference types (like arrays or classes) it applies comparison by address.

You will learn more about the class String and the comparison of strings in the chapter about "Strings".

Logical Operators

Let’s recall the logical operators in C#. They are often used to construct logical (Boolean) expressions. The logical operators are: &&, ||, ! and ^.

Logical Operators && and ||

The logical operators && (logical AND) and || (logical OR) are only used on Boolean expressions (values of type bool). In order for the result – of comparing two expressions with the operator && – to be true (true), both operands must have the value true. For instance:

|

bool result = (2 < 3) && (3 < 4); |

This expression is "true", because both the operands: (2 < 3) and (3 < 4) are "true". The logical operator && is also called short-circuit, because it does not lose time in additional unnecessary calculations. It evaluates the left part of the expression (the first operand) and if the result is false, it does not lose time for evaluating the second operand – it’s not possible the end result to be "true" when the first operand is not "true". For this reason it is also called short-circuit logical operator "and".

Similarly, the operator || returns true if at least one of the two operands has the value "true". Example:

|

bool result = (2 < 3) || (1 == 2); |

This example is "true", because its first operand is "true". Just like the && operator, the calculation is done fast – if the first operand is true, the second is not calculated at all, as the result is already known. It is also called short-circuit logical operator "or".

Logical Operators & and |

The operators for comparison & and | are similar to && and ||, respectively. The difference lies in the fact that both operands are calculated one after the other, although the final result is known in advance. That’s why these comparison operators are also known as full-circuit logical operators and are used very rarely.

For instance, when two operands are compared with & and the first one is evaluated "false", the calculation of the second operand is still executed. The result is clearly "false". Likewise, when two operands are compared with | and the first one is "true", we still evaluate the second operand and the final result is nevertheless "true".

We must not confuse the Boolean operators & and | with the bitwise operators & and |. Although they are written in the same way, they take different arguments (Boolean or integer expressions) and return different result (bool or integer) and their actions are not identical.

Logical Operators ^ and !

The ^ operator, also known as exclusive OR (XOR), belongs to the full-circuit operators, because both operands are calculated one after the other. The result of applying the operator is true if exactly one of the operands is true, but not both simultaneously. Otherwise the result is false. Here is an example:

|

Console.WriteLine("Exclusive OR: "+ ((2 < 3) ^ (4 > 3))); |

The result is as follows:

|

Exclusive OR: False |

The previous expression is evaluated as false, because both operands: (2 <3) and (4 > 3) are true.

The operator ! returns the reversed value of the Boolean expression to which it is attached. Example:

|

bool value = !(7 == 5); // True Console.WriteLine(value); |

The above expression can be read as "the opposite of the truth of the phrase "7 == 5". The result of this pattern is True (the opposite of False). Note that when we print the value true it is displayed on the console as "True" (with capital letter). This "defect" comes from the VB.NET language that also runs in .NET Framework.

Conditional Statements "if" and "if-else"

After reviewing how to compare expressions, we will continue with conditional statements, which will allow us to implement programming logic.

Conditional statements if and if-else are conditional control statements. Because of them the program can behave differently based on a defined condition checked during the execution of the statement.

Conditional Statement "if"

The main format of the conditional statements if is as follows:

|

if (Boolean expression) { Body of the conditional statement; } |

It includes: if-clause, Boolean expression and body of the conditional statement.

The Boolean expression can be a Boolean variable or Boolean logical expression. Boolean expressions cannot be integer (unlike other programming languages like C and C++).

The body of the statement is the part locked between the curly brackets: {}. It may consist of one or more operations (statements). When there are several operations, we have a complex block operator, i.e. series of commands that follow one after the other, enclosed in curly brackets.

The expression in the brackets which follows the keyword if must return the Boolean value true or false. If the expression is calculated to the value true, then the body of a conditional statement is executed. If the result is false, then the operators in the body will be skipped.

Conditional Statement "if" – Example

Let’s take a look at an example of using a conditional statement if:

|

static void Main() { Console.WriteLine("Enter two numbers."); Console.Write("Enter first number: "); int firstNumber = int.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); Console.Write("Enter second number: "); int secondNumber = int.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); int biggerNumber = firstNumber; if (secondNumber > firstNumber) { biggerNumber = secondNumber; } Console.WriteLine("The bigger number is: {0}", biggerNumber); } |

If we start the example and enter the numbers 4 and 5 we will get the following result:

|

Enter two numbers. Enter first number: 4 Enter second number: 5 The bigger number is: 5 |

Conditional Statement "if" and Curly Brackets

If we have only one operator in the body of the if-statement, the curly brackets denoting the body of the conditional operator may be omitted, as shown below. However, it is a good practice to use them even if we have only one operator. This will make the code is more readable.

Here is an example of omitting the curly brackets which leading to confusion:

|

int a = 6; if (a > 5) Console.WriteLine("The variable is greater than 5."); Console.WriteLine("This code will always execute!"); // Bad practice: misleading code |

In this example the code is misleadingly formatted and creates the impression that both printing statements are part of the body of the if-block. In fact, this is true only for the first one.

|

Always put curly brackets { } for the body of “if” blocks even if they consist of only one operator! |

Conditional Statement "if-else"

In C#, as in most of the programming languages there is a conditional statement with else clause: the if-else statement. Its format is the following:

|

if (Boolean expression) { Body of the conditional statement; } else { Body of the else statement; } |

The format of the if-else structure consists of the reserved word if, Boolean expression, body of a conditional statement, reserved word else and else-body statement. The body of else-structure may consist of one or more operators, enclosed in curly brackets, same as the body of a conditional statement.

This statement works as follows: the expression in the brackets (a Boolean expression) is calculated. The calculation result must be Boolean – true or false. Depending on the result there are two possible outcomes. If the Boolean expression is calculated to true, the body of the conditional statement is executed and the else-statement is omitted and its operators do not execute. Otherwise, if the Boolean expression is calculated to false, the else-body is executed, the main body of the conditional statement is omitted and the operators in it are not executed.

Conditional Statement "if-else" – Example

Let’s take a look at the next example and illustrate how the if-else statement works:

|

static void Main() { int x = 2; if (x > 3) { Console.WriteLine("x is greater than 3"); } else { Console.WriteLine("x is not greater than 3"); } } |

The program code can be interpreted as follows: if x>3, the result at the end is: "x is greater than 3", otherwise (else) the result is: "x is not greater than 3". In this case, since x=2, after the calculation of the Boolean expression the operator of the else structure will be executed. The result of the example is:

|

x is not greater than 3 |

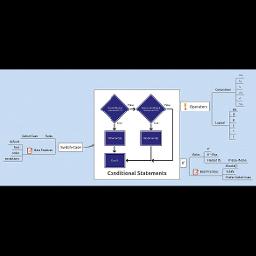

The following scheme illustrates the process flow of this example:

Nested "if" Statements

Sometimes the programming logic in a program or an application needs to be represented by multiple if-structures contained in each other. We call them nested if or nested if-else structures.

We call nesting the placement of an if or if-else structure in the body of another if or else structure. In such situations every else clause corresponds to the closest previous if clause. This is how we understand which else clause relates to which if clause.

It’s not a good practice to exceed three nested levels, i.e. we should not nest more than three conditional statements into one another. If for some reason we need to nest more than three structures, we should export a part of the code in a separate method (see chapter Methods).

Nested "if" Statements – Example

Here is an example of using nested if structures:

|

int first = 5; int second = 3;

if (first == second) { Console.WriteLine("These two numbers are equal."); } else { if (first > second) { Console.WriteLine("The first number is greater."); } else { Console.WriteLine("The second number is greater."); } } |

In the example above we have two numbers and compare them in two steps: first we compare whether they are equal and if not, we compare again, to determine which one is the greater. Here is the result of the execution of the code above:

|

The first number is greater. |

Sequences of "if-else-if-else-…"

Sometimes we need to use a sequence of if structures, where the else clause is a new if structure. If we use nested if structures, the code would be pushed too far to the right. That’s why in such situations it is allowed to use a new if right after the else. It’s even considered a good practice. Here is an example:

|

char ch = 'X'; if (ch == 'A' || ch == 'a') { Console.WriteLine("Vowel [ei]"); } else if (ch == 'E' || ch == 'e') { Console.WriteLine("Vowel [i:]"); } else if (ch == 'I' || ch == 'i') { Console.WriteLine("Vowel [ai]"); } else if (ch == 'O' || ch == 'o') { Console.WriteLine("Vowel [ou]"); } else if (ch == 'U' || ch == 'u') { Console.WriteLine("Vowel [ju:]"); } else { Console.WriteLine("Consonant"); } |

The program in the example makes a series of comparisons of a variable to check if it is one of the vowels from the English alphabet. Every following comparison is done only in case that the previous comparison was not true. In the end, if none of the if-conditions is not fulfilled, the last else clause is executed. Thus, the result of the example is as follows:

|

Consonant |

Conditional "if" Statements – Good Practices

Here are some guidelines, which we recommend for writing if, structures:

- Use blocks, surrounded by curly brackets {} after if and else in order to avoid ambiguity

- Always format the code correctly by offsetting it with one tab inwards after if and else, for readability and avoiding ambiguity.

- Prefer switch-case structure to of a series of if-else-if-else-… structures or nested if-else statement, if possible. The construct switch-case we will cover in the next section.

Conditional Statement "switch-case"

In the following section we will cover the conditional statement switch. It is used for choosing among a list of possibilities.

How Does the "switch-case" Statement Work?

The structure switch-case chooses which part of the programming code to execute based on the calculated value of a certain expression (most often of integer type). The format of the structure for choosing an option is as follows:

|

switch (integer_selector) { case integer_value_1: statements; break; case integer_value_2: statements; break; // … default: statements; break; } |

The selector is an expression returning a resulting value that can be compared, like a number or string. The switch operator compares the result of the selector to every value listed in the case labels in the body of the switch structure. If a match is found in a case label, the corresponding structure is executed (simple or complex). If no match is found, the default statement is executed (when such exists). The value of the selector must be calculated before comparing it to the values inside the switch structure. The labels should not have repeating values, they must be unique.

As it can be seen from the definition above, every case ends with the operator break, which ends the body of the switch structure. The C# compiler requires the word break at the end of each case-section containing code. If no code is found after a case-statement, the break can be omitted and the execution passes to the next case-statement and continues until it finds a break operator. After the default structure break is obligatory.

It is not necessary for the default clause to be last, but it’s recommended to put it at the end, and not in the middle of the switch structure.

Rules for Expressions in Switch

The switch statement is a clear way to implement selection among many options (namely, a choice among a few alternative ways for executing the code). It requires a selector, which is calculated to a certain value. The selector type could be an integer number, char, string or enum. If we want to use for example an array or a float as a selector, it will not work. For non-integer data types, we should use a series of if statements.

Using Multiple Labels

Using multiple labels is appropriate, when we want to execute the same structure in more than one case. Let’s look at the following example:

|

int number = 6; switch (number) { case 1: case 4: case 6: case 8: case 10: Console.WriteLine("The number is not prime!"); break; case 2: case 3: case 5: case 7: Console.WriteLine("The number is prime!"); break; default: Console.WriteLine("Unknown number!"); break; } |

In the above example, we implement multiple labels by using case statements without break after them. In this case, first the integer value of the selector is calculated – that is 6, and then this value is compared to every integer value in the case statements. When a match is found, the code block after it is executed. If no match is found, the default block is executed. The result of the example above is as follows:

|

The number is not prime! |

Good Practices When Using "switch-case"

- A good practice when using the switch statement is to put the default statement at the end, in order to have easier to read code.

- It’s good to place first the cases, which handle the most common situations. Case statements, which handle situations occurring rarely, can be placed at the end of the structure.

- If the values in the case labels are integer, it’s recommended that they be arranged in ascending order.

- If the values in the case labels are of character type, it’s recommended that the case labels are sorted alphabetically.

- It’s advisable to always use a default block to handle situations that cannot be processed in the normal operation of the program. If in the normal operation of the program the default block should not be reachable, you could put in it a code reporting an error.

1. Write an if-statement that takes two integer variables and exchanges their values if the first one is greater than the second one.

2. Write a program that shows the sign (+ or -) of the product of three real numbers, without calculating it. Use a sequence of if operators.

3. Write a program that finds the biggest of three integers, using nested if statements.

4. Sort 3 real numbers in descending order. Use nested if statements.

5. Write a program that asks for a digit (0-9), and depending on the input, shows the digit as a word (in English). Use a switch statement.

6. Write a program that gets the coefficients a, b and c of a quadratic equation: ax2 + bx + c, calculates and prints its real roots (if they exist). Quadratic equations may have 0, 1 or 2 real roots.

7. Write a program that finds the greatest of given 5 numbers.

8. Write a program that, depending on the user’s choice, inputs int, double or string variable. If the variable is int or double, the program increases it by 1. If the variable is a string, the program appends "*" at the end. Print the result at the console. Use switch statement.

9. We are given 5 integer numbers. Write a program that finds those subsets whose sum is 0. Examples:

- If we are given the numbers {3, -2, 1, 1, 8}, the sum of -2, 1 and 1 is 0.

- If we are given the numbers {3, 1, -7, 35, 22}, there are no subsets with sum 0.

10. Write a program that applies bonus points to given scores in the range [1…9] by the following rules:

- If the score is between 1 and 3, the program multiplies it by 10.

- If the score is between 4 and 6, the program multiplies it by 100.

- If the score is between 7 and 9, the program multiplies it by 1000.

- If the score is 0 or more than 9, the program prints an error message.

11. * Write a program that converts a number in the range [0…999] to words, corresponding to the English pronunciation. Examples:

- 0 --> "Zero"

- 12 --> "Twelve"

- 98 --> "Ninety eight"

- 273 --> "Two hundred seventy three"

- 400 --> "Four hundred"

- 501 --> "Five hundred and one"

- 711 --> "Seven hundred and eleven"

1. Look at the section about if-statements.

2. A multiple of non-zero numbers has a positive product, if the negative multiples are even number. If the count of the negative numbers is odd, the product is negative. If at least one of the numbers is zero, the product is also zero. Use a counter negativeNumbersCount to keep the number of negative numbers. Check each number whether it is negative and change the counter accordingly. If some of the numbers is 0, print “0” as result (the zero has no sign). Otherwise print “+” or “-” depending on the condition (negativeNumbersCount % 2 == 0).

3. Use nested if-statements, first checking the first two numbers then checking the bigger of them with the third.

4. First find the smallest of the three numbers, and then swap it with the first one. Then check if the second is greater than the third number and if yes, swap them too.

Another approach is to check all possible orders of the numbers with a series of if-else checks: a≤b≤c, a≤c≤b, b≤a≤c, b≤c≤a, c≤a≤b and c≤b≤a.

A more complicated and more general solution of this problem is to put the numbers in an array and use the Array.Sort(…) method. You may read about arrays in the chapter “Arrays”.

5. Just use a switch statement to check for all possible digits.

6. From math it is known, that a quadratic equation may have one or two real roots or no real roots at all. In order to calculate the real roots of a given quadratic equation, we first calculate the discriminant (D) by the formula: D = b2 - 4ac. If the discriminant is zero, then the quadratic equation has one double real root and it is calculated by the formula: ![]() . If the value of the discriminant is positive, then the equation has two distinct real roots, which are calculated by the formula:

. If the value of the discriminant is positive, then the equation has two distinct real roots, which are calculated by the formula: ![]() . If the discriminant is negative, the quadratic equation has no real roots.

. If the discriminant is negative, the quadratic equation has no real roots.

7. Use nested if statements. You could use the loop structure for, which you could read about in the “Loops” chapter of the book or in Internet.

8. First input a variable, which indicates what type will be the input, i.e. by entering 0 the type is int, by 1 is double and by 2 is string.

9. Use nested if statements or series of 31 comparisons, in order to check all the sums of the 31 subsets of the given numbers (without the empty one). Note that the problem in general (with N numbers) is complex and using loops will not be enough to solve it.

10. Use switch statement or a sequence of if-else constructs and at the end print at the console the calculated points.

11. Use nested switch statements. Pay special attention to the numbers from 0 to 19 and those that end with 0. There are many special cases!

You might benefit from using methods to reuse the code you write, because printing a single digit is part of printing a 2-digit number which is part of printing 3-digit number. You may read about methods in the chapter “Methods”.

Demonstrations (source code)

Download the demo examples for this chapter from the book: Conditional-Statements-Demos.zip.

Discussion Forum

Comment the book and the tasks in the : forum of the Software Academy.

Tags: best practices, book, C#, C# book, Conditional Statement "switch-case", Conditional Statements "if" and "if-else", conditional statements in C#, English, free, if-else, Nakov, operators if, programming, read online5 responses to “Chapter 5. Conditional Statements”

Leave a Reply to Conditionals – Learn C# Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

![clip_image003[26] clip_image003[26]](https://introprogramming.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/clip_image00326_thumb.png)

these are not solutions, solutions to me are exactly that. If someone gets so far, then gets stuck can’t complete the exercises, do not burst their brain with advanced algebra. Show the program that actually solves the problem you posed in the first place. Don’t try and be a smart arse.

[…] Chapter 5. Conditional Statements […]

string str = “beer”;

string anotherStr = str;

string thirdStr = “be” + ‘e’ + ‘r’;

Console.WriteLine(“str = {0}”, str);

Console.WriteLine(“anotherStr = {0}”, anotherStr);

Console.WriteLine(“thirdStr = {0}”, thirdStr);

Console.WriteLine(str == anotherStr); // True – same object

Console.WriteLine(str == thirdStr); // True – equal objects

Console.WriteLine((object)str == (object)anotherStr); // True

Console.WriteLine((object)str == (object)thirdStr); // False

For the example above, even the last one produces true. I think it is because operator == uses Equals internally, and Equals itself is a virtual method.

[…] Useful Link: http://www.introprogramming.info/english-intro-csharp-book/read-online/chapter-5-conditional-stateme… […]

[…] Useful Link: http://www.introprogramming.info/english-intro-csharp-book/read-online/chapter-5-conditional-stateme… […]