Chapter 23. Methodology of Problem Solving

In this chapter we will discuss one recommended practice for efficiently solving computer programming problems and make a demonstration with appropriate examples. We will discuss the basic engineering principles of problem solving, why we should follow them when solving computer programming problems (the same principles can also be applied to find the solutions of many mathematical and scientific problems as well) and we will make an example of their use. We will describe the steps, in which we should go in order to solve some sample problems and show the mistakes that can occur when we do not follow these same steps. We will pay attention to some important steps from the methodology of problem solving, that we usually skip, e.g. the testing. We hope to be able to prove you, with proper examples, that the solving of computer programming problems has a "recipe" and it is very useful.

Content

- Video

- Presentation

- Mind Maps

- In This Chapter

- Basic Principles of Solving Computer Programming Problems

- Use Pen and Paper

- Generate Ideas and Give Them a Try!

- Decompose the Task into Smaller Subtasks

- Verify Your Ideas!

- If a Problem Occurs, Invent a New Idea!

- Choose Appropriate Data Structures!

- Think about the Efficiency!

- Implement Your Algorithm!

- Write the Code Step by Step!

- Test Your Solution!

- General Conclusions

- Exercises

- Solutions and Guidelines

- Discussion Forum

Video

Presentation

Mind Maps

Basic Principles of Solving Computer Programming Problems

You probably think this chapter is about an idle talk like "first think, then act" or "be careful when you write and try to not miss something". In fact this chapter will not be so tedious and boring and will give you some practical guidelines for solving algorithmic problems as well as other problems.

Without making any claim of completeness, we will give you some important suggestions, based on Svetlin Nakov’s personal experience acquired during his work of 10+ years as a competitor in International and Bulgarian programming competitions. Svetlin has gained tens of International awards from programming contests including medals from International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) and has been training students from Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski (SU), New Bulgarian University (NBU), Technical University of Sofia (TU-Sofia), National Academy for Software Development (NASD), and Telerik Software Academy, and his experience during the last 10 years confirms that this methodology works well in practice.

Let’s start with the first key suggestion.

The use of a pen and sheet of paper and the making of drafts and sketches when solving problems is something normal and natural, which every experienced mathematician, physicist and software engineer does when tasked with a non-trivial problem.

Unfortunately, our experience with students showed us most of the novice programmers do not even bring with them a pen and paper. They have the false perception that in order to solve programming problem they only need a keyboard. Most of them need some time and exams’ failures to finally realize that the making of some kind of drafts on paper is crucial for understanding the problem and constructing a correct solution.

|

Everyone who does not use a pen and paper will be in a serious trouble when solving computer programming problems. It is important always to make drafts of your ideas on paper or blackboard before even start typing on the keyboard. |

Maybe, it is a little old-fashioned, but the "era of the paper" is not over yet! The easiest way for you to visualize your idea is to put it on paper. It is very difficult for most people to try and think about a problem without some kind of visualization. The visual system in the human brain, which absorbs information, is strongly connected to these parts of the brain, which are responsible for the creative potential and logical thinking.

People who have well-developed their visual system in the brain are able to easily "see" the solution of a problem in their mind. Then they only have to polish their idea and implement it. These people actively use their visual memory and their ability to create visual imagery, which is the reason why they can quickly create ideas and reflect on algorithms for solving problems. These people can quickly recognize and discard the wrong ideas and visualize the correct algorithm for the programming problem in a matter of seconds. Regardless of whether you are a "visual" type of person or not, writing down and sketching your idea is very useful and will most certainly help your thoughts on the matter. Most people have the ability to easily present information to the brain visually.

Think for example, how hard it is for you to multiply five digit numbers in your head and how less effort does it cost when you use a pen and paper (we eliminate the possibility of using electronic calculating devices, of course). It is basically the same with problem-solving, when you need a clear view on the problem you should use pen and paper. When you need to check for flaws in your algorithm, you should make some calculations using a pen and paper. When you need to think about a case in which your algorithm might not work, you should use pen and paper. That’s why you should always use pen and paper!

Generate Ideas and Give Them a Try!

As we have mentioned previously, the first thing to do is to sketch some sample examples for the problem on a piece of paper. When we have a real example of the problem in front of us, we can reflect on it and the ideas come.

When the idea is a fact, we need more examples in order to check if it is a good one. Then we need some more examples, drafted on paper to verify it again. We should be completely sure our solution is correct. Then we should go through our solution one more time, step by step, the same way like one actual computer program would do, and see if everything runs correctly.

The next thing to do is to try "breaking" our solution and thinking of a case, in which our idea would not work properly (a counter-example). If we fail at that, then our idea is probably right. If our solution definitely has a flaw, we should think of a way to fix it. If our idea does not pass every test, we should invent a new one. Not always the first idea that comes to your mind is the right one and is a true solution of the problem.

Problem-solving is an iterative process, which represents the invention of ideas and then testing them over different examples until you reach one, which seems to work correctly with every example that you could think of.

Sometimes it can take hours for you to try and find the right solution of a given problem. This is completely normal. Nobody has an ability to instantly find the correct solution of a problem, but surely the more experience you have the faster the good ideas will come. If a particular problem has something in common with one that you have solved in the past, then the proper idea will come to your mind more quickly, because one of the basic characteristics of the human brain is to work with analogies. The experience you get from solving given type of problems will help you with the invention of ideas for a solution of other analogical problems.

In order to generate ideas and test them it is mandatory to have a piece of paper, pen and different examples, which you need to visualize with the help of drafts, sketches or other means. That can help you a lot to quickly try different ideas and reflect on the solutions, which can occur to you. The basic things you need to do when you solve problems is to logically think of some problems that are analogical to the current one, summarize or try to use general ideas and then construct your solution using pen and paper. When you have a sketch in front of you it is easier to imagine what could possibly go wrong. This might give you an idea for the next step or make you give up your current idea entirely. In this way we can get a complete algorithm, the correctness that can be tested by a specific example.

|

The problem solving starts with the invention of ideas and testing them. This is best done with a pen and paper in hand and sample sketches and drafts to help you think. Always test your ideas and solutions with proper examples! |

The recommendations given above are also very useful in one more case – when you are at a job interview. Every experienced interviewer could agree, that when he gives an algorithmic problem to the interviewee he expects from him to take a pen and piece of paper, to reflect on the problem out loud and to give different suggestions for the solution. This is a sign this person can think and has a proper approach to the problem solving. Thinking out loud and rejecting different ideas shows that the interviewee has the right thinking. Even if he fails to solve the problem, this behavior will make a good impression to the interviewer!

Decompose the Task into Smaller Subtasks

Complex tasks can always be divided into smaller more manageable subtasks. We will show this with some examples below. There is not a single complex problem in this world that has been solved with one try. The correct formula for solving such a task is to split it into smaller simpler tasks, which have to be independent and different from one another. If these smaller subtasks prove to be complicated, we should split them again. This technique is called "divide and conquer" and it is in use since the time of the Roman Empire.

The division of the problem into smaller units is easier said than done. The essence of solving algorithmic problems is in the good technique of division of the given task into simpler subproblems and, of course, the invention of good ideas that can be achieved with gaining more experience.

|

Complex tasks can always be divided into smaller more manageable subtasks. When you have to solve big complicated tasks, you should always try to divide it into simpler problems, which are easier to solve. |

"Cards Shuffle" Problem – Example

Let’s give the following example: we have one ordered deck of cards and we have to shuffle it in random order. Let’s assume that the deck is represented as an array or list of N objects (every card is an object). These types of tasks require multiple repeating steps (series of removal, placing, replacing and realignment of elements). Each of these steps itself is simpler, easier and more manageable subtask, than the "Cards Shuffle" task as a whole. If we succeed in decomposing the complex task into smaller subtasks, we will basically find the right way to solve the problem. Exactly this is the essence of the algorithmic thinking: the ability to decompose complex problems into smaller ones and then find the correct solutions for them. Of course, this principle can be applied not only to programming problems, but also to ones from other scientific disciplines like math and physics. In fact this algorithmic thinking is the reason why the mathematicians and the physicists show a rapid progress when they begin to learn computer programming.

Now let’s go back to the given task and think about how to find the simple subtasks, which are needed in order to meet the requirements to randomly shuffle the cards.

If we take one deck of cards in our hands or try to sketch something on paper (e.g. series of rectangular cells, each of them representing one card), some ideas instantly come up, for example we need to change or realign elements from the deck.

Thinking like this, we can easily reach the conclusion we need to make more than one swap of one or more cards. If we make only one swap, the deck of cards would not be completely random. Therefore we need many simpler operations for a single swap (exchange).

We reached the point where we do the first decomposition into smaller subtasks: we need series of swaps, which can be considered as smaller tasks, a part of the bigger problem.

First Subtask: a Single Swap

How do we make a single swap of cards in the deck? We can answer this question in many ways and take the first idea that come to our mind. If it is any good, we will use it. Otherwise we will think of something else.

Our first idea can be: if we have a deck of cards, we can split it at random card and then separate and swap the two parts. Now do we have an idea for a single swap? Yes, we have. The next thing to do is to check if our solution is working properly (we will demonstrate this after a while).

Now let’s go back to the base task: after applying our idea, we need the deck of cards to be randomly shuffled. Now we split and swap it many times and check the result. It seems that our algorithm works fine and the subtask "single swap" will do the work.

Second Subtask: Choosing a Random Number

How to generate a random number and use it to split the deck? If we have N cards, we need a random number between 1 and N-1, don’t we?

In order to solve this problem we might need an additional help. If we know that in .NET Framework this task is already solved, we can simply use the integrated random number generator.

Otherwise we have to think of a solution e.g. we can read one line from the keyboard and then measure the time span between the start of the program and the pressing of the button [Enter]. Since the time of every input is different (especially, if we report with accuracy to nanoseconds), we have a way to calculate a random number. The only problem now is to find a way to place this number in the interval [1…N-1] and probably most of us will remember that we can use the remainder of its division by (N-1).

We can see that even the simplest subtasks can be divided into smaller tasks, which sometimes can be already solved for us. When we find a suitable solution for the current subtask, we need to go back to the base problem and test everything and see if it is working correctly put together. Let’s do that now, shall we?

Third Subtask: Combining Swaps

Let’s go back to the main task. We have reached the conclusion we have to make as many "single swap" operations as needed to ensure the deck of cards will be correctly shuffled. This idea seems right and we should try it.

Now this raises the question how many operations "single swap" are enough? Are 100 enough? Aren’t they too many? And what about 5 times? In order to give a good answer to this question, we need to think for a while. How many cards do we have? If we have several cards in the deck, we need fewer swaps. And if we have many cards, we need much more swaps, right? Therefore the number of swaps depends on the number of cards in the deck.

To see how many swaps are enough, we can take one standard deck of cards. How many cards are there in one standard deck? Most of us know there are 52 cards in it. Well then try to figure out how many "single swap" operations are needed to randomly shuffle one deck of 52 cards. Are 52 enough? It seems enough because if we swap 52 times at random position it is likely that we will split the deck at every card (this conclusion is clear even if we do not know anything about Probability and Statistics). 52 "single swap" operations seem too much, isn’t it? Let’s think of even smaller number. What about the half of the number 52? It seems fine as well, but it would be more difficult to explain why.

Some of you probably think that the best way to find the correct number is to use complex formulas from the probability theory, but does it make any sense? The number 52 is small enough and there is no need to look for other number. One loop of 52 iterations is fast enough. The cards in the deck would not be billions, would they? Therefore we do not have to think in that direction. We assume that the correct number of "single swap" equals the number of the cards in the deck – neither too big nor too small. And this is the end of the current subtask.

Another Example: Sorting Numbers

Let’s think of another example. We are given an array of numbers and our task is to sort it in ascending order. There is an abundance of algorithms for this problem and some of them conceptually different from one another. Even you could think of some ideas to solve this problem, some of them would be right and others – not quite.

So we have to solve this task and we are not allowed to use built-in .NET Framework sorting methods. The first obvious thing to do is to take a pen and piece of paper and to think of one example and then to reflect on the task. Thus we can invent multiple and very different ideas like:

- First idea: we can find the smallest number, print it and then remove it from the array of numbers. The next thing to do is to repeat the same action until the array is empty. Thinking like this, we can decompose this task into simpler tasks: finding the smallest number in array; deleting a number from array; printing a number.

- Next idea: we can find the smallest number and put it at the first position of the array (swap operation). Then we can do the same action for the rest of the array. Since we have already placed number on the first position, we go to the next one. If we repeat this k times, we will have the first k smallest numbers from the array at the first k positions. This approach takes us naturally to a task, which can be very easily divided into smaller subtasks: finding the number with the smallest value in a part of the array and exchanging the positions of two numbers from the array. The second subtask can be divided one more time: removing an element from a given position and placing an element at a given position.

- Another idea, which uses a method, conceptually different from the previous two solutions: we split the array into two subarrays with approximately the same number of elements. Then we sort them individually and finally we merge them into one. We can do this action recursively with every subarray until every one of them holds exactly one element. Array with one element is a sorted one. Here, like in the previous two ideas, we can divide the complex problem into smaller more manageable problems: splitting one array into two parts with approximately equal number of elements; merging two arrays into one big array.

There is no need to continue, right? It is obvious that every one of you can think of several different solutions or you can read about the subject in a book about algorithms. We demonstrated that every complicated problem can be divided into smaller simpler problems. These is a correct approach to solving computer programming problems – to think of the big task like it is a collection of smaller easier subtasks. This technique may be hard to learn, but in time you will get used to it.

It seems that we have figured out everything. We have an idea. It seems to work properly. The only thing for us to do is to check if our idea is correct or it is only correct in our minds. After that we can start with the implementation.

How to verify an idea? Usually this happens with the help of some examples. We should choose examples that fully cover all different cases, which our algorithm should be able to pass. The sample examples should not be too easy for your algorithm, but also they should not be so hard to be sketched. We call these certain types of examples "good representatives of the common case".

E.g. if our task is to sort an array in ascending order, then a suitable example would be an array with 5-6 elements. Two of the numbers in the array should be equal and the other – different. The numbers should be randomly placed in the array. This is a good example, because it covers most of the common cases, in which our algorithm should work.

There are many inappropriate examples for the sorting numbers problem that could not help you test your idea properly. For example if you use an array of only two elements. Your solution could work correctly with it, but your core idea could be completely wrong. Another inappropriate example is an array of equal numbers. Every sorting algorithm would work correctly with it. And another bad example – we can use an array that is already sorted. Algorithm could also work correctly and yet the idea could be wrong.

|

When verifying your ideas, choose your examples carefully. They should be simple and easy enough for you to be able to sketch them down by hand in a minute and at the same time they should represent most general case in which your idea should work. Your examples should be good representatives of the common case and cover as much cases as possible without being too big and complicated. |

"Cards Shuffle" Problem: Verifying the Idea

Let’s think of one sample example for our "Cards Shuffle" task. Let’s say we have 6 cards. In order our example to be good, our deck of cards should not be too small (e.g. 2-3 cards), because in this way our example might become very easy. Also, if we want to easily check our idea with the deck, it should not be too big. Initially it is a good idea to get six cards and order them in the deck. In this way it would be easier for us to see if the cards are well shuffled or partially shuffled or not shuffled at all. So one of the smartest things to do is to choose 6 cards regardless of their suit and order them by value.

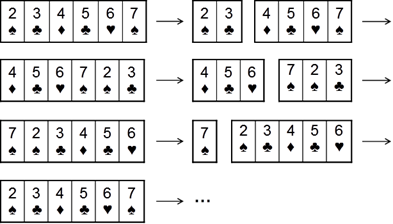

Now we already have one example, which is a good representative of the common case of our problem. Let’s now sketch it down on a piece of paper and check our algorithm on it. We should split the deck into two parts, at a random position 6 times and then swap them. Our cards are ordered by value. At the end we expect them to be randomly shuffled.

Let’s see what is going to happen:

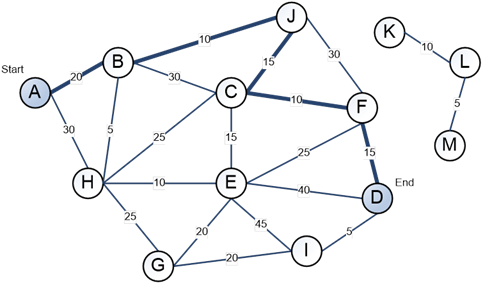

There is no need to do 6 swaps. After only 3 swaps we came back to the starting position. This is probably not an accident. What happened? We have just found an error in our algorithm. When we reflect on the problem we can see that with every swap at a random position we rotate the deck to left and after N times it goes to the starting position. So it was a good thing that we tested our idea before even started writing some code, wasn’t it?

Sorting Numbers: Verifying the Idea

It is time to check our first idea considering the sorting numbers problem. We can easily see if it is right or wrong. We start with an array of N elements and we find the smallest number, print it and then delete it from the array N times. Even if we do not sketch the idea, it seems faultless. Still let’s think of one example and see what is going to happen. We take 5 numbers, two of them are equal: 3, 2, 6, 1, 2. We have 5 steps to do:

1) 3, 2, 6, 1, 2 → 1

2) 3, 2, 6, 2 → 2

3) 3, 6, 2 → 2

4) 3, 6 → 3

5) 6 → 6

Seems like our algorithm works properly. Our result is correct and we do not have a reason to think that our idea will not work with any other example.

If a Problem Occurs, Invent a New Idea!

When you find your idea is incorrect, the obvious thing to do is to invent a new, better idea. We can do this in two ways: we can either try to fix our old idea or create a completely new one. Let’s see how this works with our cards shuffle problem, shall we?

|

The creating of a solution for a computer programming problem is an iterative process, which consists of inventing ideas, verifying them and sometimes, when problem occurs, inventing new ones. Sometimes the first idea that comes to our mind is the right one, but most of the times we need to go through many different ideas until we reach the best one. |

Let’s go back to our card shuffle problem. Firstly let’s see why our premier idea is wrong and is it possible to fix it? The problem here is easily recognized: the continuous splitting and card swapping does not shuffle them randomly; it simply rotates them to left.

How to fix this algorithm? We need to think of a new and better way to make a "single swap" operation, don’t we? Our new idea for one single swap is: randomly choose two cards from the deck and swap their places. If we do this N number of times, we would probably get randomly shuffled deck. This idea looks better than the previous one and maybe it would work correctly this time. We already know that before we even start thinking of implementing our new algorithm it is better to check it and see if it is working properly. We can verify our idea by using pen and paper and the example with the 6 cards that we used above.

In this moment we think of an even better idea, instead of choosing 2 random cards from the deck, why not just pick one random card and swap it with the first card from the deck? Isn’t this idea simpler and easier to implement? The result should be random too. Let’s start by choosing a random card at position k1 and swap it with the first card. Now we have a random card at the first position and the first card is at the k1 position. On the next step of the algorithm we pick another card at random position k2 and then swap it with the card from the first position (previously the card from the position k1). It is apparent that with only 2 steps we have changed the place of the first, the k1-st and the k2-nd cards from the deck with random cards. It seems that at every step one card changes its position with a random one. After N number of steps we can expect that every card from the deck has changed its position averagely one time. Hence our solution is working and the cards should be well shuffled.

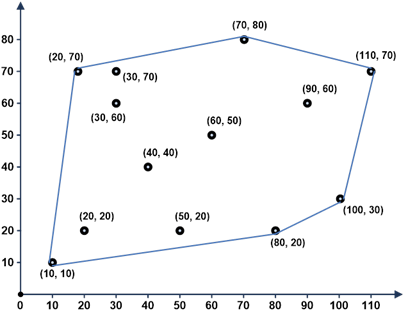

Now we should test our new idea. Does it work properly? Let’s make sure that what has happened last time will not happen again, shall we? Let’s thoroughly check this idea as well. Again, we can take the 6 cards example, which represents most of the general cases of the card shuffle problem (good representative of the common case). Then use the new algorithm and shuffle them. We should do this 6 times in a row. This is the result:

From the example above we can see that the result is correct – we have randomly shuffled six cards. If our algorithm works well with 6 cards, it should work with decks with different number of cards as well. If we are not sure in that, we should think of another more complicated example and then test the algorithm again.

Otherwise we could avoid drawing new examples and continue with our task.

Let’s summarize what we have done so far and how with consecutive actions we have figured out a solution for our problem. As we have gone through every step, we have done so far the following steps:

- We have used a sheet of paper and pen to sketch a deck of cards. We have visually represented the deck of cards as an array of boxes.

- As we already have a visual feedback, we could easily think of some sample ideas: firstly we should make some kind of a single swap operation and secondly we do this N number of times.

- We had decided that our "single swap" operation was going to be splitting the deck at random position into left and right part and then swap them.

- We have decided that we should do this "single swap" as much times as the number of cards in the given deck.

- We have considered the problem of choosing a random number, but have finally decided to use a ready solution for the job.

- We have decomposed the main problem into three smaller subtasks: "single swap" operation; choosing a random split point; combining a sequence of "single swap" operations.

- We have checked our idea for mistakes and found one. It was a good thing to check it when we did, because it was not too late to fix it.

- We have thought of a new, more reliable solution of the single swap operation.

- We have checked our new idea with an appropriate example and we assured ourselves that this time the solution was right.

Now we finally have a working idea, backed up with good examples. This is the most important thing to do in order to solve a given problem – inventing of the algorithm. The easier part remains – the implementation of our idea. Let’s see how this can be done.

Choose Appropriate Data Structures!

If we already have a correct and working idea for the solution of the problem, the next thing to do is to write the program code. We have missed something, right? What have we missed? Have we done everything necessary to be able to write fast, easy and trouble-free implementation of our solution?

The thing that we have missed is the manner in which our idea (which we have checked on a sheet of paper) is going to be implemented as a computer program. The implementation is not always a simple task and sometimes it requires additional ideas. This is the next major step: to think of our ideas in terms of the computer programming. This means to think for specific data structures and not for abstract ones like "card" and "deck". We should choose the right data structures, which are going to help us build a correct solution.

|

Before you even start with the implementation of your idea, you should choose the proper data structures. It may turn out that your current idea is not as good as it seems. The solution could be inefficient or difficult to implement. It is better to figure this out before you write any programming code! |

In our case we have spoken of swapping one card from the deck with another, but in terms of programming this means to swap two elements from specific data structure (i.e. array, list or something else). We have reached the moment where we have to choose one data structure and show you how it is done.

What Kind of Data Structure Should We Use?

The first question that comes to our mind is: What kind of data structure should we use? We may have all kinds of different ideas for data structures, but not all of them can do the work. Let’s reflect for a while, shall we? We have a collection of cards and the way in which the cards are ordered matters. That’s why we need a data structure that can hold a collection of elements and keep their order.

Can We Use an Array?

The first thing we can think of is using the structure "array". The array structure is the simplest data structure, which can hold a collection of elements. The array also keeps the order of the elements (first, second, third and so on) and we can reach each element by index. The array has a fixed number of elements and we cannot change its size during the execution of the program.

Is the array the correct data structure for us? To answer this question we have to know what kind of operations we are going to apply on the deck, represented as an array, and whether they are feasible and efficient.

What kind of operations are we going to apply in order to implement our algorithm? Let’s enumerate them:

- Choosing a random card. Since we can access every element from the array by index we can easily pick a random position k between the interval [1…N-1].

- Swapping the first card with the k-positioned one (single swap). After choosing the random card, we should swap it with the first one. Again this operation seems easy enough. We can do the swap with three simple steps and one temporary variable.

- More operations that we might use: initialization of the deck; traversing the deck; printing the deck. All these operations seem trivial when applied on array.

It seems that one simple data structure like the array can represent a deck of cards quite well.

Can We Use Another Data Structure?

It is normal to ask ourselves whether an array is the best data structure for our problem. It seems that every operation that we use in our algorithm can be applied efficiently to the array.

But still, let’s try and think of an even better data structure for the deck of cards than the array. What other options do we have?

- Linked list – we do not have an indexer and it will be difficult for us to access element at a random position.

- Array with a non-defined size (List<T>) – this structure seems to have all the benefits of the arrays and we can apply every operation to it as well. If we use List<T>, we increase our comfort – we can easily remove and add elements, which may help us to initialize the deck faster and do some other helpful operations.

- Stack / queue – the deck of cards does not have a behavior of FIFO or LIFO, so these structures are not appropriate for our algorithm.

- Sets (TreeSet<T> / HashSet<T>) – with the use of sets we lose the original order of the elements which is a major obstacle. The use of sets is inappropriate.

- Hash table – the structure card deck is not from the type key-value, so the structure hash table cannot store the deck efficiently. Also it does not allow us to keep the original order of the elements.

Generally speaking, we have just covered the basic data structures, which can hold a collection of elements. We have reached the conclusion that either array or List<T> will be suitable for the job. List<T> is more flexible than the ordinary array, so we decide to use List<T> to represent our deck of cards.

|

The choice of data structure begins with the consideration of all key operations that we are going to perform on it. Next we analyze all suitable structures and choose the one that will be the most efficient and easiest to use. And sometimes we should make a compromise between efficiency and the simplicity. |

How to Represent the Other Data Objects?

We have already decided how to represent our deck of cards and now we should do the same with the other objects that we are going to use in our algorithm. If we think about it, it seems that beside the two objects a "card" and "deck", which we use in our algorithm, we do not use other data objects.

The next question that arises is how to represent a single card? We can represent it as a string, number or class, which has two fields – face and suit. There are, of course, other variants, which have their advantages and disadvantages.

Before we even start considering which of these representations of one card is "the best", we should go back to the requirements of the task. It suggests that we are given a deck of cards (as an array or list) and our task is to shuffle it. How a card is represented is not of importance in the task. So it does not matter what we shuffle, we could shuffle cards, chess figures, boxes of tomatoes or other objects. We have an ordered collection of elements and we need to randomly shuffle it. The fact that we shuffle cards is not significant for our task, that’s why we do not need to waste time to choose the best way to represent one card. Let’s use the first thing that come to our mind, i.e. we will define a class Card with 2 fields – Face and Suit. Even if we use a number between 1 and 52 to represent one card, it still does not change anything. We shall not discuss this any further.

Sorting Numbers: Choosing a Data Structures

Let’s go back to the sorting numbers problem and choose an appropriate data structures for it too. We choose to use the simplest algorithm that we could think of: to pick the smallest number until we can, print it and after that delete it. This solution can be easily sketched on a piece of paper and checked for errors.

Again, in order to answer this question we need to figure out what kind of operations we are going to use in our algorithm. The operations are as follows:

- Searching for the smallest number in the structure.

- Removing of the previously found smallest number.

Obviously, the use of an array is not reasonable, because we need the operation "remove". The use of List<T> seems better, because both operations can be simply and easily implemented. Data structures like stack or queue have a little use for us, because we do not have a LIFO or FIFO behavior. There is not much sense to use a hash table, because the "search by value" operation is not fast, despite the fact that the removal of an element should be very efficient.

Let’s talk about the two sets – HashSet<T> and TreeSet<T>. The two sets have one major problem. They cannot contain elements with an equal value. Despite that let’s see what they can do. The HashSet<T> is not of any interest, because like the hash tables it does not support efficient way to find the element with the smallest value. The data structure TreeSet<T>, however, looks very promising. Let’s take a look, shall we?

The TreeSet<T> class is a balanced search tree by design, so it supports the operation "finding the smallest element". That’s interesting, isn’t it? Now we have a new solution for the task, we put all the input elements in a TreeSet<T> and then we get the smallest from the set until it remains empty. Easy, simple and very efficient. The two operations, which we want, are internally implemented (searching for the smallest number and deleting it).

While we skim through the documentation, we figure out something very interesting: the TreeSet<T> stores its elements ordered by value. And this is the solution of our problem, right? Therefore if we keep all the input elements in a TreeSet<T> and then traverse the ordered set (with the help of the built-in enumeration), we will have all the elements ordered by value. Problem solved!

We are now very happy, we found one very nice way to solve our task, but soon we discover one major problem: TreeSet<T> does not store two elements with the same value. I.e. if we add the number 5 several times, at the end there will be only one entry with a value 5. Eventually we will lose some of the input elements irreversibly.

Naturally we want this problem fixed. If there was a way to store how many times one number occurs in a set that would solve our problem. Then we think of the SortedDictionary<K,T>. This class can store ordered keys, which have a value. We can store the number of occurrences of a key in its corresponding value. We can traverse all the elements and then store the number of occurrences in the SortedDictionary<K,T>. Although it seems our problem is solved, it is not going to be implemented as elegant and simple as with List<T> or TreeSet<T>.

If we read the documentation of the SortedDictionary<K,T> carefully, we will find that this class internally uses a red–black tree and some day we can implement that this type of sorting is very famous and it is called a Binary Tree Sorting (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_tree_sort).

With this little demonstration we showed you how when you put some thoughts into the selection of the best data structures, you can come up with some new solutions for the problem. We start with an algorithm, which leads us to a new, better one. This is normal to happen during the process of consideration of our algorithm and not after we have written 300 lines of code, which we will then have to be redone. This is another proof it is better to firstly think of the best data structures and then to start writing the programming code.

Again, it seems we should grab the keyboard and start writing a programming code. And again, it is better not to hurry. The thing is that we have not thought of something very important: the efficiency and performance of our algorithm.

|

You should think of efficiency before writing even a line of a programming code. Otherwise, you risk to waste time implementing an algorithm, which is inefficient and slow. |

Let’s return to our "card-shuffle" problem. We have a working idea for solving the problem (we have invented the algorithm). The idea appears to be correct (we have checked the algorithm with examples). We should not have any problems implementing our idea (we are going to use List<Card> for the deck and class Card for a single card). Everything seems fine, but let’s think about how many cards we are going to shuffle. Is our idea going to work fast enough when using the chosen data structures?

How to Estimate the Performance of Given Algorithm?

How fast is our algorithm? To answer this question we should estimate how many operations it performs when shuffling one deck of 52 cards.

For one deck of 52 cards our algorithm makes 52 "single swap" operations, do you agree? How many elementary operations cost one "single swap"? 4 operations: the choice of one random card; the placing of the first card in a temporary variable; the replacing of the first card with the random card; the replacing of the random card with the first card (from the temporary variable). How many operations does our algorithm do? They are approximately 52 * 4 = 208.

Are 208 operations too much? Let’s do a loop with 208 iterations. Are they too much? Give it a try! We can assure you that one loop with 1,000,000 iterations on a modern computer goes imperceptibly fast, and one with 208 – for an insignificant amount of time. Therefore we can easily conclude that our algorithm has a good performance. Our algorithm is extremely fast when working with 52 cards.

Despite the fact that in reality we rarely play cards with more than 1 – 2 decks, let’s assume that we have 50,000 cards in the deck. Let’s estimate the performance of our algorithm with a large number of cards. We have 50,000 single swap operations and each of them consists of 4 operations, which makes about 200,000 operations, which are going to be executed for a small amount of time as well.

The Efficiency Is a Matter of Compromise

Finally we can conclude that our algorithm is efficient and will work well even with decks with large amount of cards. Here we had luck. Usually the things are not so simple and we must make a compromise with the performance and the efforts, which we put, when we implement our algorithm. For example if we sort numbers, we can solve this problem in minutes when we use some of the simplest sorting algorithms. We can also do this much more efficiently when we use some of the more complex algorithms, but that will waste more of our time (in searching and reading books and Internet).

Is it worth it? We should consider that. If we have to sort 20 numbers, it does not matter which algorithm we are going to use. It will always be fast, even with the most naive algorithm. If we are going to sort 20,000 numbers, the algorithm matters, and if we need to sort 20,000,000, we should look at the task from a completely new angle. The efforts for solving efficiently the problem of sorting 20,000,000 numbers is far more than the efforts for writing a straightforward algorithm to sort 20 numbers. We should answer the question: is it worth it?

|

The efficiency is a matter of compromise – sometimes it does not worth to complicate your algorithm and put time and effort to make it work faster. But occasionally the performance is crucial and we should pay serious attention to it. |

Sorting Numbers: Estimating the Performance

It is obvious that the performance depends on whether a particular task requires it. And now let’s return to the sorting numbers problem, because we want to show you that the efficiency is directly related to the right choice of data structures.

Let’s go back to the point where we have decided what kind of data structures to use for keeping the input data. Which is better: List<T> or SortedDictionary<K,T>? Shouldn’t we use a data structure that we know well instead of some complex structure that we have never used? Do you know well red-black trees (the internal implementation of the SortedDictionary<K,T>)? With what are they better than List<T>? In fact it may turn out that you do not need to answer this question after all.

If we have to sort 20 numbers, does it matter what data structure are we going to use? We can choose the simplest algorithm and the first data structure that is actually suitable for the job and that’s it. It does not matter how fast is the algorithm and the data structure, because the numbers are not so many.

But if we have to sort 300,000 numbers, then everything is different. We should carefully study how exactly the class SortedDictionary<K,T> behaves. We should figure out how fast is the "search" operation. How fast does this data structure add elements? How fast can you traverse through every element of the collection? If we read the documentation of the class we will see that the adding of an element takes on average log2(N) steps, where N is the number of the elements in the structure. After few simple mathematical calculations (which require additional skills), we can roughly estimate that we need about 5-6 million steps to sort all numbers. For 300,000 numbers this number is reasonably small.

Similarly we can prove that the search and delete operations in List<T> with N elements take N steps. Therefore for 300,000 elements we will need roughly 2 * 300,000 * 300,000 steps. In fact this number is an approximate guess, because at the beginning we have one number in the list, not 300,000 elements. Nevertheless this estimation is approximately right, maybe a bit rough but right. We can see that the number of steps needed in this case is extremely large, that is why here the simple algorithm will not work properly (the program might "hang").

And again we reach a point where we need to choose between one simple and one complex algorithm. One of them can be very easily but slow when implemented. The other is more efficient, but very difficult to implement and we will probably need an additional reading of documentation and thick books in order to correctly estimate the performance. Everything is a matter of compromise.

Naturally, at this point we can think of some of the other algorithms that we have considered previously. And precisely, to split the array into two parts then to sort them separately (by a recursive call) and then merge the two parts into one sorted array. As we consider this algorithm we will find that this solution will work efficiently with such structures like the dynamic array (List<T>). This sorting algorithm has an average and worst-case performance of n*log(n) steps, where n is the count of the elements in the array. This algorithm will work efficiently with 300,000 numbers. Let’s not go any further, if you want more details about the algorithm you should read more about MergeSort in Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merge_sort).

We have finally reached the time where we can start with the implementation of our solution. We already have a working idea, we have chosen the best data structure and now it is the time to start writing the programming code. If we have not done some of the previous steps, we should go back to them before start writing the code.

|

If you do not have an invented idea, do not start writing programming code! What are you going to write if you do not have a working idea? This is like to go to the train station and get on the first train that you can see, without even deciding where you are going. |

This is typical for novice programmers: once they see the requirements, they proceed with the writing of the programming code. After some time, that they waste in a pursuit of wrong ideas (that occur to them during the writing), they realize that it is better to stop and think a bit more about the solution. This whole concept is wrong and the main goal of this chapter is to protect you from this frivolous and very inefficient approach to problem-solving.

|

If you have not checked your ideas, there is no sense to start implementing them! Is it necessary to write 300 lines of code before implementing that your idea is totally wrong? Is it necessary for you to start over? |

The implementation of already invented and checked idea is very easy and simple. But the implementation itself requires additional skills and mostly experience. The more experience you have the faster and easier it will be for you to write efficient programming code. With lots of practice, which will come with time, you will become very skilled in writing high-quality code and you will be able to write code faster. If you want to know more about high-quality programming code you should read the chapter "High-Quality Programming Code". But for now let’s focus on the implementation of our ideas.

We assume that you should already know the basic steps needed to write programming code: you know how to work with the development environment (Visual Studio), the compiler; how to understand the error messages and use the "auto complete" function; how to create methods, constructors and properties and fix errors and use the debugger. Therefore these next advices are not so much connected with the writing itself but with the overall approach when writing programming code.

Have you written 200-300 lines of code without even compiling or testing it? Do not do that! Do not write large lumps of code at one time, instead you should write small parts and then test them.

How to write code step by step? This depends on the given task and the way, in which it is decomposed into smaller tasks. For example if the main task consists of 3 independent parts, we should write one of them, compile and test it with a proper input data until we are sure that it works correctly. After that we move to the second part – write code, compile, test and then proceed with the third part with the same approach and finally integrate the parts and test everything as a whole.

Why to write code step by step? Because we reduce the amount of code that we have to concentrate on in any given moment. By treating the problem in parts, we decrease its complexity. Remember: the large and complicated task could always be divided into several smaller and simpler subtasks. And it is always easier to solve simple problems.

When writing large chunks of code, without compiling it, we accumulate a great amount of errors, which could easily be avoided by a simple compilation. The modern programming environments (like Visual Studio) try to recognize the syntactic errors automatically while we are writing the code. Use this function and fix the obvious coding errors as early as possible. Early troubleshooting takes less time and nerves. However if we delay the troubleshooting, it could cost us a lot of efforts, sometimes even rewriting the whole programming code.

When you write a huge amount of code, which is not tested, and decide to test it as a whole with some input data, you usually receive a lot of errors, which can be avoided if one just compiles. The larger the code is, more difficult it is to be fixed. These problems could be caused by a variety of reasons: incorrect use of data structures; wrong algorithm; badly structured code; bad condition in the if-statement; wrongly implemented loop; going out of bounds of the array and many other problems that could have been fixed earlier. Do not wait for the last moment. Eliminate the mistakes as soon as possible!

|

Write your program in parts, not at once! Take, write and compile one logically independent part, fix the errors, test it and if it works fine, move to the next part. |

Writing Code Step by Step – Example

In order to demonstrate how to write code step by step, we should illustrate it with the "card-shuffle" algorithm that we invented previously.

Step 1 – Defining the Class "Card"

Our task is to shuffle the card deck, so let’s start with the definition of the class "card". If we do not have an idea of how to represent one single card, we could not have any idea how to represent a deck as well. Therefore it will not be possible to define a method for shuffling the cards. We have already agreed the representation of one card does not matter, so any kind of them might work.

We will define a class "card" with fields face and suit. We will use a string variable for the face of the card (with possible values: "2", "3", "4", "5", "6", "7", "8", "9", "10", "J", "Q", "K" or "A") and enumerable variable for the suit of the card (possible values: "Club", "Diamond", "Heart", "Spade"). The class Card might look like the following code:

|

Card.cs |

|

class Card { public string Face { get; set; } public Suit Suit { get; set; }

public override string ToString() { string card = "(" + this.Face + " " + this.Suit + ")"; return card; } }

enum Suit { CLUB, DIAMOND, HEART, SPADE } |

For comfort we have overridden the method ToString() for the class Card. In this way we could easily print a single card on the console. We have defined enumerable type for the Suit.

Testing of the Class "Card"

Some of us would probably proceed with writing the code, but if we follow the principle "Writing Code Step by Step", we should firstly compile and test how the class Card works.

In order to do so, we can write a small simple program to initialize a single card (e.g. Ace of Clubs) and print it on the console. This will check whether our class Card, its constructor and its ToString() method work correctly:

|

static void Main() { Card card = new Card() { Face="A", Suit=Suit.CLUB }; Console.WriteLine(card); } |

We start the program and check if the card is printed correctly. We should see the following:

|

(A CLUB) |

Step 2 – Creating and Printing a Deck of Cards

Before we proceed with the main task (randomly shuffling the deck of cards) we should try to initialize and print a whole deck of 52 cards. Thus we will be completely sure that the input data for the card-shuffle method is correct. Based on our previous analysis on the data structures, we should use List<Card> in order to represent the deck. Let’s create and print a deck of five cards, shall we? Later we can try with a full deck of 52 cards.

|

CardsShuffle.cs |

|

class CardsShuffle { static void Main() { List<Card> cards = new List<Card>(); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "7", Suit = Suit.HEART }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "A", Suit = Suit.SPADE }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "10", Suit = Suit.DIAMOND }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "2", Suit = Suit.CLUB }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "6", Suit = Suit.DIAMOND }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "J", Suit = Suit.CLUB }); PrintCards(cards); }

static void PrintCards(List<Card> cards) { foreach (Card card in cards) { Console.Write(card); } Console.WriteLine(); } } |

Printing the Deck – Testing the Code

Before we proceed forward, let’s start the program and verify the output result. It seems that there are no mistakes, the result is correct:

|

(7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) |

Step 3 – Single Swap

Let’s implement the next step to the task solution – the subtask "single swap". When we have a logically independent piece of code, the best thing to do is to extract it as a separate method. We should think of what is our input and output. Our input should be a single deck of cards (List<Card>). As a result of its work the method should change the input deck List<card>. The method should not return any result, because it does not create a new List<Card>, it just operates with the already created and submitted list.

What should be the name of the method? Following the recommendations for working with methods, we should give "descriptive" name (with 1-2 words) what the method is for. Suitable name for it is: PerformSingleSwap(…). The name clearly describes what the method does: executes a single swap.

Let’s firstly define the method and then write its body. This is a good practice, because before we proceed with the implementation of the method, we should be aware: what does it do; how does it work and what is its name. Here it is the definition of the method:

|

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { // TODO: Implement the method body } |

The next thing to do is to write the body itself. Firstly let’s recall the algorithm: we choose one random number k in the interval between 1 and the length of the array minus 1 and then swap the element at the position k with the first element. Everything seems easy, but how do we generate a random number in a given interval with the language C#?

Search in Google!

When we encounter a common problem, which we cannot solve, but we are sure that many people have faced it, the easiest way to cope with it is to search for information in Google. We should adequately structure our search. In our case we look for sample C# code, which returns as a result a random number in a given interval. We could try the following search:

|

C# random number example |

Among the first results there is a C# program, which uses the class System.Random for generating a random number. Now we have a direction in which we look for a solution. We know that in .NET Framework there is a standard class called Random, which serves for generating random numbers.

After that we could try to guess how this class works (most of the times it takes less time to guess instead of reading the documentation). We are trying to find an appropriate static method for generating a random number, but it seems there is none. Then we make an instance and search for a method, which could return a number in given a diapason. We have luck, there is a method Next(minValue, maxValue), which returns what we need.

Let’s try to write the whole code for the method. We have the following:

|

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { Random rand = new Random(); int randomIndex = rand.Next(1, cards.Count - 1); Card firstCard = cards[1]; Card randomCard = cards[randomIndex]; cards[1] = randomCard; cards[randomIndex] = firstCard; } |

Single Swap – Testing the Code

The next step is to test the code. Before proceeding forward, we have to be sure that the single swap (exchange) operation works properly. We do not want to find an eventual problem just when we test the "card-shuffle" method with the entire deck? It is better when there is a problem to be found immediately and when there is none, to continue forward with confidence. We act step by step – before going to the next step we should make sure that the current step is working fine. For this purpose we make a small test program, let’s say with 3 cards (2♣, 3♥ and 4♠):

|

static void Main() { List<Card> cards = new List<Card>(); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "2", Suit = Suit.CLUB }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "3", Suit = Suit.HEART }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "4", Suit = Suit.SPADE }); PerformSingleSwap(cards); PrintCards(cards); } |

Let’s perform several times a single swap operation with our 3 cards. The first card (card 2♣) is supposed to be with one of the other two cards (cards 3♥ or 4♠). We execute the program several times in a sequence. We should expect the half of the obtained results to contain (3♥, 2♣, 4♠) and the other half – (4♠, 3♥, 2♣), shouldn’t we? Let’s see what is going to happen. We start the program and see the following results:

|

(2 CLUB)(3 HEART)(4 SPADE) |

We start it again and again and the result is the same – no swap is made. How is that possible? What has just happened? Did we miss to execute the single swap before printing the cards? There is something wrong here. It seems that the program did not make even one swap in the deck of cards. How did this happen?

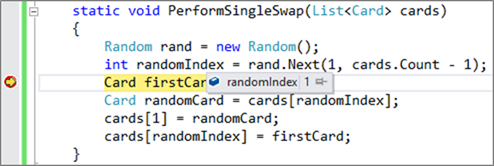

Single Swap – Correcting the Mistakes

It is obvious that there is a mistake. Let’s put a breakpoint and follow what is happening via the debugger of Visual Studio:

It is clear that during the first execution the random position happens to be one. This is acceptable so we continue on. When we look the code we follow, we notice that we swap the random element at index 1 with the element at position 1 i.e. with itself. We apparently did something wrong. And then we remember that indexing in List<T> is zero-based i.e. the first element is at position 0. We immediately change the code:

|

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { Random rand = new Random(); int randomIndex = rand.Next(1, cards.Count - 1); Card firstCard = cards[0]; Card randomCard = cards[randomIndex]; cards[0] = randomCard; cards[randomIndex] = firstCard; } |

We start the program several times and we get unexpected results, again:

|

(3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) (3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) (3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) |

It seems that the random number is not so random. What to do now? Do not rush to blame .NET Framework, CLR, Visual Studio and all other usual suspects! It is possible that the mistake is ours. Let’s look at the execution of the method Next(…). Since cards' count is 3, we always call Next(1, 2) and expect from it to return a number between one and two. It seems correct but if we read what the documentation says for the method Next(…), we will notice that the second parameter should be one unit bigger than the upper border we want to obtain.

We were wrong about the diapason of the random number that we selected. We correct the code and once again we test it to see how it works. After the second correction we get the following results:

|

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { Random rand = new Random(); int randomIndex = rand.Next(1, cards.Count); Card firstCard = cards[0]; Card randomCard = cards[randomIndex]; cards[0] = randomCard; cards[randomIndex] = firstCard; } |

Here are the possible results after several executions of the previous method:

|

(3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) (4 SPADE)(3 HEART)(2 CLUB) (4 SPADE)(3 HEART)(2 CLUB) (3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) (4 SPADE)(3 HEART)(2 CLUB) (3 HEART)(2 CLUB)(4 SPADE) |

It seems that after enough executions the first card is replaced by each of the other two cards i.e. we have a random swap indeed and every card has the equal chance to be randomly chosen. We are finally ready with the method "single swap". It is better that we found these two mistakes now and not later when the whole program is supposed to start working, right?

Step 4 – Card Shuffling

The last step is simple: we use the single-swap method N times:

|

static void ShuffleCards(List<Card> cards) { for (int i = 1; i <= cards.Count; i++) { PerformSingleSwap(cards); } } |

We now can put it all together. We combine all the pieces of code we already wrote, tested and we checked they work correctly. The entire code of our program looks like this:

|

CardsShuffle.cs |

|

using System; using System.Collections.Generic;

class CardsShuffle { static void Main() { List<Card> cards = new List<Card>(); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "2", Suit = Suit.CLUB }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "6", Suit = Suit.DIAMOND }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "7", Suit = Suit.HEART }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "A", Suit = Suit.SPADE }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "J", Suit = Suit.CLUB }); cards.Add(new Card() { Face = "10", Suit = Suit.DIAMOND });

Console.Write("Initial deck: "); PrintCards(cards);

ShuffleCards(cards); Console.Write("After shuffle: "); PrintCards(cards); }

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { Random rand = new Random(); int randomIndex = rand.Next(1, cards.Count); Card firstCard = cards[0]; Card randomCard = cards[randomIndex]; cards[0] = randomCard; cards[randomIndex] = firstCard; }

static void ShuffleCards(List<Card> cards) { for (int i = 1; i <= cards.Count; i++) { PerformSingleSwap(cards); } }

static void PrintCards(List<Card> cards) { foreach (Card card in cards) { Console.Write(card); } Console.WriteLine(); } } |

Card Shuffling – Testing

Now we only need to test whether the algorithm for shuffling a deck of cards works correctly. Here is the output of our program:

|

Initial deck: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) After shuffle: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) |

As we can see, we encounter a problem: after the shuffle the cards did not change their order. We run the program several times and the result is the same. Did we forget to call the card-shuffling method ShuffleCards?

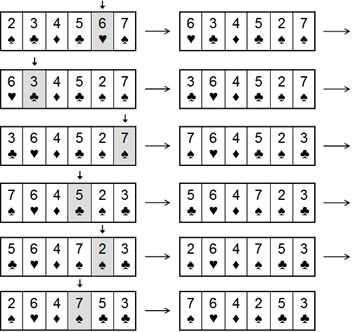

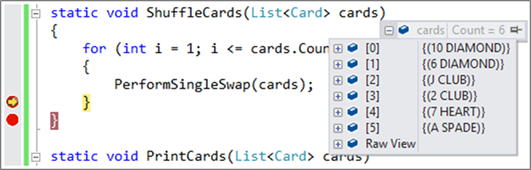

We take a close look at our source code: everything looks fine. We decide to set a breakpoint after the call of the method PerformSingleSwap(…) in the body of the loop, responsible for the shuffling of the cards. We run our program in debugging mode by pressing the [F5] button. After the first stop of the debugger at our breakpoint everything seems good – the first card is exchanged with another one, as it supposed to. After the second stop of the debugger everything is still all right – a random card is swapped with the first one. We continue tracing the program execution with the debugger and everything seems to work just fine.

The card shuffling program works flawlessly when we run it step by step through the Visual Studio debugger:

But why is the final result wrong? We decide to set another breakpoint in the body of ShuffleCards(…) at the end. The debugger stops and at this point and the result is still correct – the cards are randomly shuffled. We continue debugging and we reach the place where we print the deck. We go pass it and the cards are printed to the console in random order. Strangely: still the correct result. What is the problem?

We start the program without debugging it with [Ctrl+F5]. The result is wrong – the cards are not shuffled. We run our program in debugging mode again with the press of [F5]. The debugger once more stops at the breakpoints and the program yet again is working without any problem. It looks like that, when we run our program in debug mode the result is correct, but when we start it normally, without the debugger, the answer is wrong. Strange indeed!

We decide to add a line of code, which is going to print the deck after every single swap:

|

static void ShuffleCards(List<Card> cards) { for (int i = 1; i <= cards.Count; i++) { PerformSingleSwap(cards); PrintCards(cards); } } |

We run our program in debug mode (with [F5]), observe the execution step by step and we find that it works correctly:

|

Initial deck: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) (A SPADE)(7 HEART)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) (6 DIAMOND)(7 HEART)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(A SPADE)(J CLUB) (J CLUB)(7 HEART)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(A SPADE)(6 DIAMOND) (2 CLUB)(7 HEART)(10 DIAMOND)(J CLUB)(A SPADE)(6 DIAMOND) (A SPADE)(7 HEART)(10 DIAMOND)(J CLUB)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND) (10 DIAMOND)(7 HEART)(A SPADE)(J CLUB)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND) After shuffle: (10 DIAMOND)(7 HEART)(A SPADE)(J CLUB)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND) |

We run again our program in normal mode (with [Ctrl+F5]) and the answer is still incorrect. Yet again we try to find out why it is happening:

|

Initial deck: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) (6 DIAMOND)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(7 HEART)(J CLUB) (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) (6 DIAMOND)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(7 HEART)(J CLUB) (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) (6 DIAMOND)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(7 HEART)(J CLUB) (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) After shuffle: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) |

We can clearly see that at every step, on which we expect to be done a single-swap, actually the same cards are swapped: 7♥ and 6♦. The only way this to happen is if every time the random number is the same. The conclusion is that we have a problem with the generation of random numbers. The random generator does not work correctly.

We instantly think about taking a look at the documentation of the class System.Random(). On MSDN we can read, that by creating a new instance of the generator of pseudo-random numbers with the constructor Random(), the generator is initialized with a value, equal to the current system time. In the documentation we can further read that by creating two or more instances of the class Random in a relatively short time span, there is a great chance the numbers to be the same. It turns that the problem consists in the misuse of the class Random.

Now being more familiar with the current problem, we could correct it by creating an instance of the class Random only once at the beginning of the program. After that, if we need a random number, we are going to use the already created generator of pseudo-random numbers. After the correction, the code looks like this:

|

class CardsShuffle { …

static Random rand = new Random();

static void PerformSingleSwap(List<Card> cards) { int randomIndex = rand.Next(1, cards.Count); Card firstCard = cards[0]; Card randomCard = cards[randomIndex]; cards[0] = randomCard; cards[randomIndex] = firstCard; } … } |

It seems that the program finally works correctly. At every run the order of the cards is different and looks randomly:

|

Initial deck: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) After shuffle: (2 CLUB)(A SPADE)(J CLUB)(10 DIAMOND)(7 HEART)(6 DIAMOND) -------------------------------------------------------- Initial deck: (7 HEART)(A SPADE)(10 DIAMOND)(2 CLUB)(6 DIAMOND)(J CLUB) After shuffle: (6 DIAMOND)(10 DIAMOND)(J CLUB)(2 CLUB)(A SPADE)(7 HEART) |

We try some other tests and the final result is still correct. Now we can say that we have a correct implementation of our algorithm, which we have designed earlier.

Step 5 – Console Input

Now we only need to be able to read the deck from the console so that the user can enter the cards, which need to be shuffled. Notice that we left this step as last. Why? The answer is pretty simple: we do not want to enter the same data at the start of our program just to check whether a piece of our code works correctly. By having the needed data hard-coded in the source code, we save a lot of time during the developing process.

|

If the problem involves entering data from the console, leave this as last step and be sure that everything else works flawlessly before implementing the reading of the input. While writing the source code, do your tests with hard-coded examples so that you don’t have to enter any data. This way you are going to save your time and your nerves. |

Data entry is a low-priority task, which everyone can handle. You only need to think of the format the cards are entered – are they entered one by one or at once; are the face and the color entered at once or separately. There is nothing difficult so we leave this to our readers.

Sorting Numbers – Step by Step

Till this moment, we showed you how important it is to write your program step by step and before proceeding to the next step you must be sure that the previous one is working correctly.

Let’s take a look at the problem of ordering numbers in ascending order. The steps for solving this problem are the same. Once again the right approach for solving this task is to work step by step. Let’s see shortly which the steps are. We are not going to write any code, but we are going to consider the main parts of the solution. Suppose that we use List<int>, in which we successively find the lowest number, print it and erase it from the list of numbers. These are the steps:

Стъпка 1. Think up a good test data (example). For example the numbers: 7, 2, 4, 1, 8 and 2. We create a List<int> and fill it with the numbers from the example. We create a method, which outputs the numbers.

We compile and test the piece of code we just wrote.

Стъпка 2. We create a method to find the lowest number in the array and return its position.

We test the method, responsible for the search of the lowest number. We try different sets of numbers to be sure that the search works correctly (we set the lowest element at the beginning, at the end, at the middle; we also consider a case when the lowest number occurs more than once).

Стъпка 3. We create a method to find the lowest number, print it and after that delete it.

We test with our example if the method works correctly. We must also try with other examples.

Стъпка 4. We create a method to sort the numbers. This method executes N times the previous one (where N is the count of the numbers).

We must test whether everything works correctly.

Стъпка 5. If data input is required we implement it after everything else.

You can see that the approach to break the main problem into smaller problems can work well for all tasks. Simply we just need to figure out which are the smaller problems, from the bigger one, and implement them. On every smaller problem implemented we need to test it. After every step we need to start our program to be sure that till this moment everything works flawlessly. In this way we are be able to find out errors quickly and debug them. It would be much faster than trying to debug them after we have written tons of code.

Does the following sound familiar to you: "I am ready with the first task so I have to start the next one."? Everybody has thought of this on an exam. But in programming to be ready with a task means:

1. I have understood well the description of the task.

2. I have come up with an algorithm to solve the problem.

3. I have tested my algorithm on a piece of paper and I am sure that is correct.

4. I have thought up for the data structures we need and for the complexity of my algorithm.

5. I have written a program, which implements my algorithm correctly.

6. I have tested my program with suitable examples so that I can be sure that everything works flawlessly, even in unusual situations.

Inexperienced software developers often forget about the last step. They think that testing is not their job, which is their biggest mistake. It is like to think that Microsoft is not supposed to test Windows and let it crash every minute.

|

Testing is an important part of the programmer’s duties. Writing code without testing is like typing on the keyboard without looking at the screen – you think that the text, you have written, is correct, but most likely it is full of bugs. |

Experienced programmers know that untested code is not finished. In most software companies it is completely unacceptable not to test your work.

In the software industry is widely spread the idea of unit testing – automatic testing of every unit of code (methods, classes and modules). Unit testing means, that for every program, we create another one, which to test our work. In some companies firstly they think up the testing scenario, build the tests and only then start working on the program. The things you should know about unit testing are quite many, but you will get more familiar with them as you get deeper in the "software engineering". For now we are going to focus on the manual testing every programmer must do. Unit testing frameworks and test automation can be used to simplify the process.

How to Test?

A program works correctly if it can handle every kind of input data. Testing is a process, which aims to find any type of bugs. It cannot detect whether a program works flawlessly, but it can help you to find most of the bugs, which cause incorrect results and other types of errors.

Sadly you can’t predict all cases and test them. Therefore you must think up examples, which cover most of the situations, which could happen. In this way you could with minimum efforts (i.e. with minimum count of simple tests) to check all common cases of usage of the program. If no bugs are found after testing, this doesn’t mean that the program works 100% correctly, but in this way we reduce the chance of the program to crash in a later phase.

|

Testing can only find the existence of bugs. It can’t prove that a program works flawlessly! Programs, which are carefully tested, have fewer bugs than untested or not carefully tested programs. |

It is good to start testing with a typical case for our program. Often this is the same example we have tested on a piece of paper and which our algorithm can handle correctly.

Normally, after the code is written we only need to fix some minor bugs so that our program can pass the test correctly. After that we have to test our program with more difficult and bigger examples to see how our program behaves in more complicated situations. We now have to test with borderline cases and test for performance. Depending on the complexity of the current task, we do from 1-2 to dozens of tests to cover the main cases of usage.

With more complicated software, i.e. Microsoft Word, the number of tests can be thousands, even hundreds of thousands. If a program’s functionality is not carefully tested you can’t say that it works correctly. Testing during software development is as important as writing the code. In big software companies for every programmer there is a tester. For example in Microsoft for every programmer, who writes the code (software developer), there are two people hired to test the code (software quality assurance engineers). Although these people do not write the main software, they write testing software and therefore we call them software engineers.

Testing with Good Examples of the Common Cases

As we already mentioned, it is good to start testing with a good example of a common situation. This is a test, which is enough simple to be written down on a piece of paper and accurate enough to cover the usual usage of the program excluding special cases. The steps are as follows:

- Think up a test, which is a good example of a common situation.

- Test this example on a piece of paper.

- Expect the program to work correctly for that test.

- Be sure that the example works correctly after the program is written and the errors in the development process are fixed.

Sadly, many programmers end their testing at this moment. Some inexperienced programmers do something even worse: think up a stupid test case (which is a special case for the current program), don’t write it down, write some code and, after the program passes the example, they continue. Don’t do like this! This is like repairing a car and once you are finished, driving it downhill, thinking that the car is repaired (but the car has no power to drive uphill).

What Else to Test For?

Testing the case, drawn on a piece of paper, is only the first step. Next you need to do some additional tests to be sure that your program works correctly:

- A hard common-case test. The goal is to check whether your program can handle a bigger and harder to compute example. For our task that kind of a test is to shuffle a deck of 52 cards.

- Borderline tests. They check whether your program can handle an unusual case, which could happen. In our case this could be shuffling a deck, which contains only one card.

- Performance tests. These tests put our program in extreme conditions. Usually these tests consist of large data, which needs to be inputted and processed.